Witnessing the preview events of the 7th Berlin Biennial and reading the immediate press responses one confronted much annoyance, dread and dissatisfaction.01 The criticisms levelled at the biennial’s experiment began early last year, with eye-rolling at the open call, Artur Żmijewski’s inaugural curatorial gesture as lead curator of the biennial. I will have to admit to looking to the sky and thinking that this was a lame and populist tactic, and was surprised when the Brussels-based Pierre Bismuth told me he sent a response – a poster showing himself against a romantic sky, accompanied by the slogan, ‘MIT PIERRE GEGEN PROPAGANDA’. He wears a leather jacket that gives his earnest glare the creepy aura of a small time gangster (quitting the bad life to go legit perhaps), and, just in case you do not find that creepy enough, he Photoshopped bugs onto the image, lending a hilariously grotesque twist to the imagined electoral campaign. During the opening days, the poster was pasted all over Berlin and many mistook it for an official part of the biennial; one critic singled it out as an exception in a sea of failed contributions. But Bismuth’s was a self-funded campaign – the other 5000+ responses were archived at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, the names and stated political affiliations, of artists who consented to have this information made public, transformed by the artist Burak Arikan into a data map. The myriad political affiliations of the applicants, unsurprisingly, hovered around the Leftist camp, though not without some colourful qualifications.

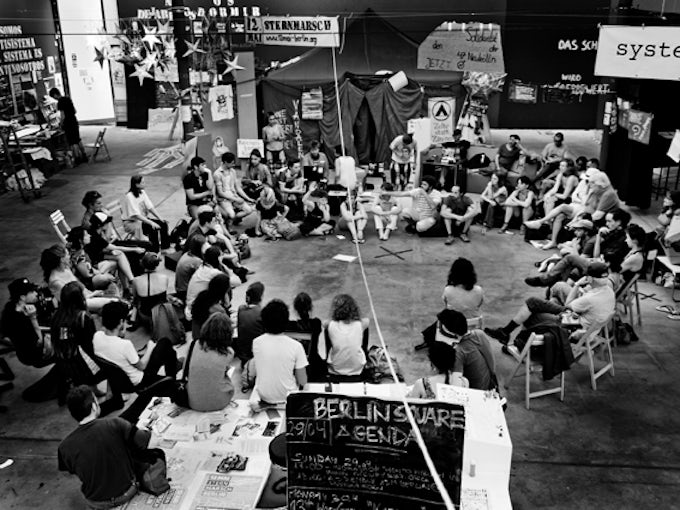

Another strike against the biennial – in the eyes of most of the people I spoke to – was the space made for the Occupy Movement and the Indignados, who were invited to set up camp in the largest exhibition space of Berlin’s KW Institute for Contemporary Art (the organiser and host central venue). Members of the Movement also arranged the seating at the press conference and led about half of the discussion, taking it to the field of journalistic responsibility in an era of struggle against social injustice. Some thought this was preaching to the converted, others saw the political force of the ‘occupation’ completely annulled by its sanctioned presence in a contemporary art gallery. The Occupiers and Indignados themselves spoke of their stance as the accepting of public money to practice democracy.

There was also frustration at the sense that there were too few artworks, though too many Polish ones; and finally utter indignation at Zmijewski’s allegedly having moulded the work of participating artists to reflect his own practice – shaping this biennial, the criticism held, into his own Gesamtkunstwerk. The antipathy was swirling so thickly by the day of the press conference that I was almost surprised to hear KW’s Gabriele Horn and Klaus Biesenbach defend the project – which they did with a spirited assertion that if KW was not the place to try out this way of doing things, where could we find such a space? To join this small rank of defenders, which I have decided to do, one has to both take stock of the criticisms that have emerged and battle one’s own reservations.

The critics point out that a lot of works in the exhibition echo Żmijewski’s artworks, and some protest the inclusion of one that is his very own (Berek, or ‘tag’, from 1999, which shows naked people playing the children’s game in a concentration camp gas chamber).02 Including your work is something of a taboo in the province of artist-curated exhibitions, but already here the question arises of whether or not Żmijewski’s biennial is best understood as an exhibition. I think not. Of course, as with many exhibitions, artist’s projects have been selected and are presented side-by-side. Berek is found on the fourth floor of KW with the seedlings from Berlin/Birkenau (2012), a self-proclaimed Holocaust memorial by Łukasz Surowiec that involves planting birch trees from the region of the former concentration camp in and around Berlin. Yet for this visitor, the floor mostly given over to seedlings signalled (as did just about every other project featured at KW) that the building was less an exhibition space in the conventional sense than an incubator, encampment or simply a temporary home.

The heterogeneous treatment of KW, the lack of labels on the walls (which made some works bleed into each other) and the fact that visitors have to rely on the guides to find out what is going on adds to the feeling of the unavailability of a well-oiled viewing machine. With the other artist’s projects profiled at KW – such as ‘A Gentrification Program’ (2012–ongoing), Renzo Martens’s school and other projects in the Congo that await construction and are present via several small, rather unremarkable photographs and an explanatory text;the Styrofoam model of the world’s tallest Jesus statue, which the sculptor Mirosław Patecki erected in the Polish town of Świebodzin; and ‘Blood Ties’, a station set up by Bogotá’s former mayor, Antanas Mockus, where medical staff collect blood pledges from visitors to stop or reduce their drug consumption– what is on view becomes increasingly difficult to understand as a self-contained form, or even the primary site of the work. Indeed, the continual confrontation with other locations, other contexts produces a sense that the gallery is decidedly not where things are ‘at’. The political potential of the gallery as a space where people gather to look together was not taken for granted, but there was a general feeling that the usual rituals of art viewing were spent. That the biennial’s opening coincided with the opening of Berlin’s ‘gallery weekend’ (their inaugural cocktail reception was bizarrely close by on Auguststrasse, but without a hair of organisational overlap) marked a kind of stand-off.

With Pawel Althamer’s section of the biennial called ‘Draftsmen’s Congress’, we enter into the realm of art as therapy, something that Żmijewski has – again rather controversially – claimed for Berek and other works involving re-enactments or collaborations with the handicapped and the traumatised. But the ‘Draftsmen’s Congress’ is more readily invoked in comparison to Żmijewski’s Oni (Them, 2007), a video documenting several antagonistic groups from post-1989 Poland engaging in non-verbal conversation through placards of their own construction, which was first presented at documenta 12 in 2007. When I showed up, there was little of the antagonism of Żmijewski’s work in Althamer’s installation – rather, a happily anarchic repurposing of every surface of the Elizabethkirche as a drawing board. Though the potential for confrontation exists, most people seem to enjoy the elementary fun of drawing. What I observed, instead of echoes of Them, was a sense of a school lesson well learnt – specifically the assignment, which both Żmijewski and Althamer were given as students in Gregorz Kowalski’s sculpture studio at the University of Warsaw’s Fine Art Department, whose title announces a sense of shared responsibility: Common Task. Rather than individualistic posturing, could the projects in the Biennial be seen as efforts shared between friends? In this light, the section of the KW installation titled ‘Breaking the News’, which involves multiple projections of footage of mass protest or performative resistance posted online by various artists and activists, would not be dismissed (as it was in one review),by way of yet another comparison to Żmijewski’s previous work (Democraciesof 2010), as if this were a ‘brand’. Rather, the artist-curator’s work would more clearly appear as one in a continuum of research undertaken by so many citizens of the era of the Internet.

To read echoes of Żmijewski’s practice in the contributions of artists he has invited, or to perceive the results as evidence of ego expansion, is too simplistic and too entrenched in a model of art that is predicated precisely on the individual artistic ego, beyond all other considerations. A different sense of personal commitment is at play in this biennial. This is not only evident through Żmijewski’s sharing of the curatorial work with Joanna Warsza and the artist’s group Vojna, who remain in St Petersburg, where they are pursued by the authorities for various violent opposition actions against the government and the police. Many curators have shared their work. But the biennial process seemed to go further in terms of reorganising the divisions of labour. Deep artistic influence is a good question, but one cannot stop at the artist-curator’s work when looking for models. Indeed Żmijewski’s efforts appear as much effected by his friends as their presentations are by him. Yael Bartana’s project is a telling case in point here.

Bartana’s Jewish Renaissance Movement in Poland emerges as an important paradigm in relation to the biennial as a whole.The movement was formed in 2007 and vigorously promoted via her exhibition for the Polish Pavilion of the 54th Venice Biennale in 2011, And Europe Will be Stunned… This title is carried over to name The First International Congress of the JRMP held at Berlin’s Hebbel am Ufer theatre (11–13 May 2012) as part of the biennial. Bartana’s work begins with her native Israel, taking it ‘as a sort of a social laboratory, always looking at it from the outside.’Even if she clearly wants to go further, stating, ‘My recent works are not just stories about two nations — Poles and Jews’, her sustaining hypothesis is grim: ‘This is a universal presentation of the impossibility of living together.’ With its transition from film productions to the founding steps of a movement (collecting memberships, organising the congress, the continual call for the migration of Israeli Jews to Poland) Bartana attempts to move beyond symbol and allegory, as do most contributions to the biennial. One gets a sense that, even if the will to improve things in the future is not entirely lost, the means of improvement – particularly the manifesto – may be hollow and tired.

Yet the role played by propaganda, both in Bartana’s work and in the promotional materials for BB7, gives one pause. In particular, we must question their penchant for deploying pseudo-fascist iconography in the movement’s logos, publications and other visual materials. This is difficult to dismiss as hollow – it certainly sends chills down my spine, something that the promotional campaigns of the last Berlin Biennials, which traded on enigma, complexity and degrees of illegibility, never achieved. Despite the fact that currency symbols and the letters and number BB7 are shown (in the Zeitung, which was passed out at the biennial) to be the components merged to create the biennial logo, the final result carries the enigmatic oomph of a swastika. Similarly, Bartana’s merging of the Polish eagle and the Star of David into the logo of her movement introduces a kind of super-nationalism. A sense of inevitability is actively bolstered by the humourless determination of the rhetoric found in Bartana’s films and manifesto as well as Żmijewski’s writing, particularly his declaration: ‘We were interested in finding answers, not asking questions.’ Regardless of how much this contradicts reality (for the organisers clearly asked plenty of questions in the process of conducting the interviews which make up their publication as well as the inaugural call), it faithfully performs a form of determinism that seems undemocratic or at least impatient with reflexivity.

Of course we can reason that these artists are acting a bit like the Slovenian experimental band Laibach, whose critique of the system (at least in Slavoj Žižek’s analysis) takes the system more seriously than it takes itself.Perhaps too, due to the frustration that Żmijewski has expressed with the political ineffectiveness of most artistic work as we know it (not to mention the strategies of the political Left which continues to lose ground to a racist populism), there is an attempt to try one’s hand at something that appears much more decisive. The question remains whether this decisve atmosphere shields the inherently fragile process of politics or whether it quashes it. I am with Bismuth here – against propaganda.

If I wish to defend the biennial it is because I see one of its greatest potentials to lie in the reanimation of a process that has long stagnated. If, at the beginning of the 1990s, the repurposing of a light industrial structure into a space of art signalled possibility and progress, the case of KW exemplifies that these moves generally followed an all too predictable path – we have tended to call this the wholesale gentrification of a neighbourhood. But perhaps the gentrification is far from complete when the army of retailers and latte peddlers move in. The invitation to the Occupy Movement and the Indignados, with their artful resistance to appearing decisive or united, to take up residence in the main exhibition space of KW gestures towards the persistence of a process of transformation – la lutte continue.

We have a biennial that is not an exhibition, and this leaves much room for working out what else art can do today. What is also clear is that the pressures of exhibiting, which a biennial naturally comes with, push this non-exhibition towards posturing that is not necessarily illustrative of its greatest potential. The problem of measuring effects makes everyone impatient, most of all Żmijewski. But the publication Forget Fear that was released ahead of the biennial also shows that he, Warsza and team have taken time to conduct an impressive oral history of precisely the type of political action rooted in art, which can help us recognise that what is so often presented as a vague horizon – something we might call political beauty – is already happening. Here the visionary work of Mockus as mayor of Bogotá is a brilliant example. Sadly, his civic mobilisations, which the book chronicles, far outshine the project he has organised in KW as part of the biennial – the latter lacks the wicked, absurdist sense of humour which made his political demands irresistible to several warring factions.

In battling the greatest psychological weapon humanity has at its disposal – fear – the courage to laugh cannot be forgotten. The 7 th Berlin Biennial does much to help us understand the enemy, but the comrade it has in laughter is strangely abandoned, perhaps mistaken once again for old ineffective irony.

Footnotes

-

The artists have been friends and have shared concerns for years, though it cannot be denied that Żmijewski is like the unhappy Bert to Althamer’s sunny Ernie.

-

The work sparked controversy as recently as last year when it was removed, following protests by Jewish groups, from an exhibition curated by Anda Rottenberg as part of Side by Side (2011), a large-scale project organised at Berlin’s Martin Gropius Bau, which attempted to chronicle Polish and German co-existence through selections of art and artefacts from the past five hundred years. Żmijewski writes in the BB7 Zeitung newspaper published on the occasion of the biennial that the presentation is in protest of this latest censorship.