The onset of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s undermined the liberalisation of social attitudes to sexuality and gender that followed the collapse of dictatorial regimes in the Iberian Peninsula and many Latin American countries. 01 As my generation was coming of age in late 1980s Spain, HIV/AIDS was said to amount to slow death, marginalisation and shame, and was heavily marked with the stigma of sexual promiscuity. And so, in the midst of an ‘epidemic of signification’, our sexuality was built on panic, disinformation, rumours, blame and mistrust. 02 Intimacy was radically politicised, and fear and silence were made accomplices.

If, as Michel Foucault argued, the power that represses a libidinous act is by nature erotic, the response to the repression ushered in by the HIV/AIDS crisis must also be an erotic one. 03Such was the premise of a recent exhibition at Tabakalera in Donostia/San Sebastián, Spain, titled ‘Anarchivo sida’ (‘AIDS Anarchive’), which displayed activist pamphlets, videos, performance documentation, books, press clips and online materials documenting the cultural responses to the crisis from the 1980s onwards, which the curatorial collective Equipo re (Aimar Arriola, Nancy Garín and Linda Valdés) has been gathering since 2012. 04 The archive didn’t pretend to be systematic or exhaustive, and neither was its geography: most materials were from Spain and Chile, with additional contributions from Colombia, Brazil and Guatemala. Instead, intimacy, love and eroticism were here harnessed against the scientific and ‘hygienic’ order of the archive. Visitors were greeted by the farewell video that Brazilian artist Rafael França made with his partner in 1991, days before his death. In it, the two are locked in an infinite embrace, documented in close-up shots. Another work by Diego del Pozo, commissioned for the exhibition, explored touch and interaction by inviting viewers to place their arms into velvety casings. Importantly, ‘AIDS Anarchive’ also attempted to look beyond the experience of white, homosexual men by addressing how other communities have responded to the crisis, namely indigenous peoples (e.g. Sexual Dissident Movement MUMS) and feminist and lesbian activist groups (e.g. LSD in Spain and Lesbians in Action in Chile).

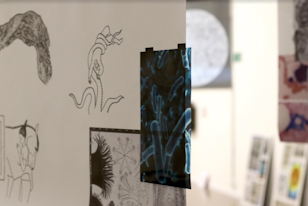

The exhibition was divided into three sections – ‘Animal’, ‘Death’ and ‘Health’ – each of which was displayed on platforms of increasing height, designed by artist Carme Nogueira, which emphasised the viewer’s bodily relation to the materials on view. In order to access the exhibits, the visitor had to empathise, to some degree, with each of these realms; it became a body that approached, sat down, peaked out. The documents displayed in the ‘Animal’ section showed how alterity is shot through with associations with the animal world: from scientific theories tracing the origins of the pandemic to African monkeys with a view to dehumanise HIV-positive men and women, to the recuperation of such homophobic terms as mariquita, mariposón, oso (which literally translate as ‘ladybug’, ‘butterfly’, ‘bear’). The Chilean collective Yeguas del Apocalipsis (Spanish for The Mares of the Apocalypse) pioneered such political identification with the animal world, as manifested in their representation of butterflies, mares, reptiles, birds, flowers, feathers and animal hides. Their very first action in 1988 was to ride through the University of Santiago de Chile, mounted nude on a white horse.

The second section, titled ‘Death’, focused on the ongoing process of collective mourning that extends from the 1980s until the present. 05 Many of the documents and works displayed in this section considered the repercussions of living with death. In 2005 Chileans Francisco Copello and Claudio Marcone performed a festive and glamorous funeral procession, in anticipation of Copello’s death one year later. That same year, Guillermo Moscoso and Fabian Crovetto convened a gathering to light candles for those who had passed, a common practice in Chile to commemorate the disappeared during the dictatorial repression.

The final section, ‘Health’, displayed materials interrogating given definitions of health and normalcy. Pamphlets by the Chilean activitist group CEPSS (Spanish acronym for Education and Prevention for Public Health and AIDS) documented their campaign to change the language framing the epidemic, for example by replacing the term ‘sick bodies’ with ‘people living with HIV’. In the video performance Tajo(Cut, 1996), Águeda Bañón opens a wound in her shoulder and licks it in a self-healing ritual. In another video, Andrés Senra interviews activist groups such as Radical Gai, LSD and RQTR, which were responsible for the introduction of queer critique in Spain in the 1990s. 06 Radical Gai, for example, campaigned to foreground questions of sexual identity and the HIV/AIDS crisis within leftist social struggles. This also led them to denounce the homophobic policies of leftist liberation struggles in Cuba and Mexico and to critique the colonialist commemorations of the quincentenary of the so-called discovery of Latin America from a queer perspective.

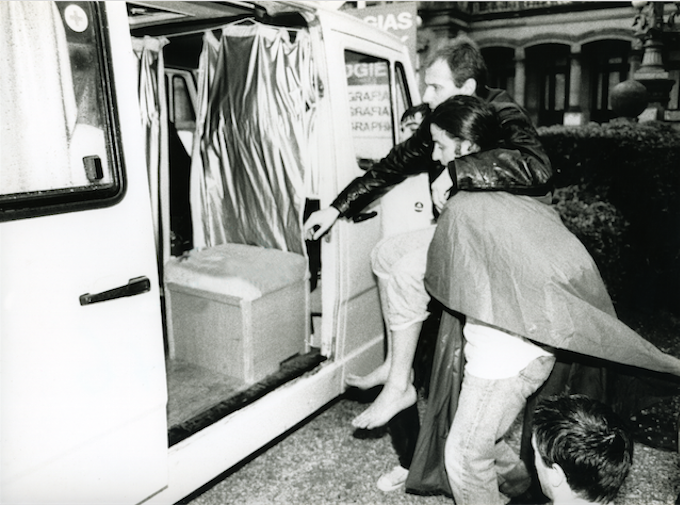

Central to the exhibition was Pepe Espaliú’s performance Carrying (1992), in which the artist’s body was carried through Donosti/San Sebastián by a chain of people. Together with SIDA DA (AIDS GIVES, 1984) by the collective Las Pekinesas (Miguel Benlloch, Tomás Navarro and Rafael Villegas), it was one of the first artworks to address the HIV/AIDS crisis in Spain. Carrying played an important role in the exhibition because it rooted it in a local context but also because of its collective methodology, which resonates with Equipo re’s own approach. Espaliú’s performance originated in a workshop at Arteleku and led to further group discussions through the foundation of the collective The Carrying Society (1992–98). Similarly, ‘AIDS Anarchive’ neither began nor ended with the exhibition presented at Tabakalera; the exhibition is part of an ongoing effort to build affective and political networks. 07

If modern archives manufactured the other from a hygienic distance, ‘AIDS Anarchive’ attempted to transgress that distance by mobilising dissident bodies and emotions; fluids, feelings, blood, sexuality, desire and love were all called upon to undo the archive’s neutralising effect. 08 The eroticism that the political manipulation of the epidemic in the 1980s and 90s aimed to suppress returned here with a vengeance: to point to the perversity of modernity itself. In the process, the notion of contagion that so marked the politics of fear of the 1980s was repurposed to shed light on the political, affective and aesthetic affinities that traversed national and identity boundaries. 09

Footnotes

-

These include the Carnation Revolution of 1974 in Portugal, the transition to democracy in Spain following the death of General Francisco Franco in 1975, the end of the military dictatorship known as the National Reorganisation Process in Argentina in 1983, the gradual democratisation of Brazilian institutions between 1974 and 1985, and the end of Pinochet’s military dictatorship in 1990.

-

Paula Treichler, ‘AIDS, Homophobia, and Biomedical Discourse: An Epidemic of Signification’, October, vol.43, AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism, Winter 1987, pp.31–70. See also Ann Cvetkovich, Archive of Feeling, Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures, Durham: Duke University Press, 2003; and Douglas Crimp, Melancholia and Moralism – Essays on AIDS and Queer Politics, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2002.

-

Paula Treichler, ‘AIDS, Homophobia, and Biomedical Discourse: An Epidemic of Signification’, October, vol.43, AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism, Winter 1987, pp.31–70. See also Ann Cvetkovich, Archive of Feeling, Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures, Durham: Duke University Press, 2003; and Douglas Crimp, Melancholia and Moralism – Essays on AIDS and Queer Politics, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2002.

-

Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction (1976, trans. Robert Hurley), London: Allen Lane, 1979. See also Slavoj Žižek, The Plague of Fantasies, London: Verso, 1997, p.48.

-

See Nancy Garín and Aimar Arriola, ‘Global Fictions, Local Struggles (or the distribution of three documents from an AIDS counter-archive in progress)’, L’Internationale Online, see: http://www.internationaleonline.org/research/politics_of_life_and_death/5_global_fictions_local_struggles_or_the_distribution_of_three_documents_from_an_aids_counter_archive_in_progress.

-

See Sara Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004.

-

Andres Senra is a member of the research group ‘Archivo Queer?’ housed at Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (MNCARS). MNCARS also supported Equipo re’s research.

-

The exhibition also established an ongoing dialogue with the local context through performances held at Tabakalera and group discussions held at different spaces throughout the city. See: https://www.tabakalera.eu/en/anarchivo-sida-equipo-re-exhibition.

-

The exhibition also established an ongoing dialogue with the local context through performances held at Tabakalera and group discussions held at different spaces throughout the city. See: https://www.tabakalera.eu/en/anarchivo-sida-equipo-re-exhibition.