Arseny Zhilyaev is an artist, writer and political activist who lives and works in Moscow. Zhilyaev’s artistic practice poses questions about the political and social legitimisation of art. Through exhibitions and participatory projects, he explores the relationship between art and social production – from the labour conditions of creative workers to the demand for, and capitalisation on, workers’ creativity. His projects often delve into the avant-garde practices of the Russian revolutionary era that attempted to bring together artistic and social concerns, elaborating on their contemporary currency for creative practices aiming to bridge art and activism. Below, Silvia Franceschini talks with Zhilyaev about his recent and upcoming projects, and the relationship between artistic production and the current socio-political context in Russia.01

SILVIA FRANCESCHINI: In April 2012, when the Moscow Occupy movement emerged, you initiated the project Pedagogical Poem, made in collaboration with historian and activist Ilya Budraitskis and held at the Presnya Historical Memorial Museum, formerly the Museum of Revolution. You organised lectures, seminars and workshops to explore the links between contemporary art, history and critical theory. Why did you choose an educational format for this work?

ARSENY ZHILYAEV: I am convinced that only projects that incorporate an educational or discursive aspect can really change the political situation in Russia. After the mass protests denouncing alleged fraud in the Russian presidential elections held in March 2012, it became clear to me that isolated actions such as those by the activist collectives Voina or Pussy Riot could no longer achieve their main political goal. When the people took to the streets they were looking for an articulated alternative. And this is, first of all, a question of democratic culture and education. Projects such as Pedagogical Poem acquire additional political meaning thanks to their educational component. Our purpose is to rethink the museum as an educational institution addressed to the wider public. This differs significantly from the anti-institutional impulse of the Occupy movement and bureaucratised contemporary art academia.

Together with Ilya Budraitskis, we are trying to find ways to articulate the new subjectivities that appeared in Russia following the period of historical amnesia caused by the ‘shock therapy’ of the 1990s, when the country plunged in a sudden and drastic economic U-turn following the collapse of the USSR. It is important to us that Pedagogical Poem takes place in the former Museum of Revolution because our purpose is to rethink the museum as an educational institution connecting history and art and addressed to the wider public. This differs significantly from both the anti-institutional impulse of the Occupy movement and bureaucratised contemporary art academia.

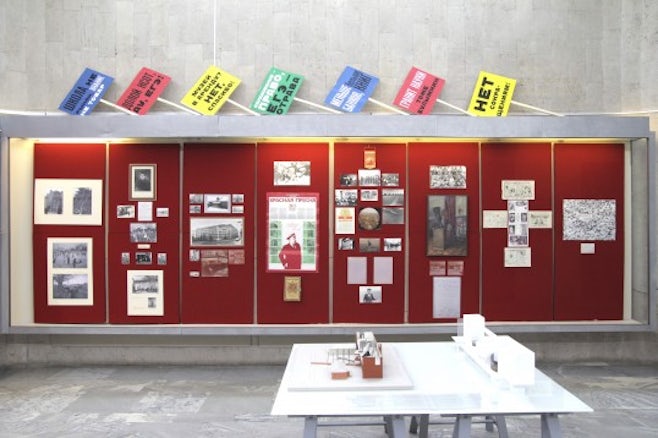

The educational programme spanned over eight months, from March to November 2012, and was attended by students, activists, historians and general public interested in art. Together with them, we devised the exhibition ‘The Archive of the Future Museum of History’, which just opened at the Presnya Historical Memorial Museum and will be on view until 6 January 2013.02

SF: You have addressed the topic of labour conditions in several projects such as the exhibitions Employment Record Book (2009) and Rare Species (2010), as well as initiatives such as the May Day Congress, a union of artists, intellectuals and activists that focuses on the rights of creative workers. How does this research bridge intellectual discourse and political activism?

AZ: All of my work is dedicated to exploring labour relations in various ways. Founded in Moscow in 2010, May Congress is an attempt at bringing together institutional initiatives in support of the rights of creative workers.03This was preceded by another initiative, the Union of Creative Workers, which I established in 2009 together with Masha Chehonadskih from Moscow Art Magazine, Nikolay Oleynikov from Chto Delat? and other artists and political activists. However, due to the lack of funds and official opportunities, we couldn’t act as a real trade union and we had to engage instead in unofficial actions in the streets, interventions in the media, lectures and artistic projects. The other two projects you mention deal with labour conditions from a curatorial perspective. For Employement Record Book, I invited artists from all over Russia to show how they were earning money to make a living – it was an exhibition about art without any art works. In Rare Species I invited not only artists, but also gallerists, curators, academics and art writers to explain, in the format that they were most comfortable with, how they became art workers. Why do people decide to work in this field? Do they consider the art world to be a successful industry? And if so, why?

SF: Your recently closed exhibition The Museum of Proletarian Culture: The Industrialisation of Bohemia (State Tretyakov Gallery, 2012) looked at the changes in artistic practice that have occurred in Russia throughout the last thirty years – from the amateur art of the late Soviet era to the commercialised post-Soviet cultural practices and the more recent self-expression via contemporary social networks. Bringing together in a single installation a selection of Soviet Realist paintings from the 1920s and 30s, artworks attributed to fictional amateur artists of the latter-day Soviet era and examples of today’s shared digital creativity, the project vindicated the value of marginalised and informal creative practices. Do you think that a new proletarian culture can emerge nowadays and, if so, how can museums support it?

AZ: Although it seems evident that the working class movement will not remain as it existed in the twentieth century – with its specific traditions, organisations and unions – this does not mean that it has completely vanished. In fact, I think that it should be redefined according to contemporary working conditions. An important reference for my installation The Museum of Proletarian Culture was Alexey Fedorov-Davydov’s ‘Experimental Marxist Exhibition’, held at the Tretyakov Gallery in 1930. Arguably nearly 50 years ahead of his time, Fedorov-Davydov tried to show the art of the oppressed to problematise the way art history was, and still is, traditionally taught – as that of the great masters. Placing artworks by a range of celebrated and unknown artists from different eras in the interiors that would have been typically occupied by their owners (such as landowners, merchants or tsars), Fedorov-Davydov’s exhibition can be seen as a pioneering installation that aimed to give form to an alternative construction of history – in this instance, a Marxist reading of the history of art that was at odds with the Stalinist promulgation of Socialist Realism as the only officially accepted art form.04I was moved by this impulse to articulate an alternative history of art, not based on the celebration of individual creativity but on the relationship between art and the relations of production of its time. Can we subject the history of art to revision today? What would it look like from the point of view of a factory worker of the 1970s or 80s? And what about the perspective of a producer of immaterial goods of the 2000s?

SF: The 705 Berlin Biennial (2012) recently opened the doors of the museum to political activism by inviting the Occupy movement to inhabit the gallery space for the duration of the show. In The Museum of Proletarian Cultureyou display the Occupy Abay Manifesto, authored by Occupy Moscow and named after the statue of the Kazakh poet Abay around which the protesters first gathered in Moscow in May 2012.06 Your proposition seems to be in line with avant-garde gestures aiming to erase the border between art and life, perhaps extending them to the dissolution of the borders between art and activism. How do you see the relationship between your artistic practice and your political activity?

AZ: Metaphorically speaking, I think that art must be prepared to accept its own death in order to develop into a political event. This is what happened to the Adbusters-initiated Occupy Wall Street movement when it turned into a global movement for direct democracy. Rising from the dead is possible, but perhaps only as an admonition to those remaining on the territory of art that there is life after death. Art should exist in the regime of the liar’s paradox: it should be open to recognising its artificial nature. In The Museum of Proletarian Culture I tried to emphasise the artificiality of museum representation. Art should exist in the regime of the liar’s paradox: it should be open to recognising its artificial nature.

However, my approach was substantially different from the 7th Berlin Biennale’s inclusion of the Occupy movement. In this case the Occupy Abay Manifesto was part of a documentary installation which also included images of the Moscow Occupy Camp, a description of the general assembly, where the text was agreed upon, and of the figure of the poet Abay. This Manifesto was important to me as an example of what can be called the revolutionary creativity of the masses: it is the creativity of real life, which does not lose its value when it becomes part of a museum installation.

SF: You often also work as a curator.07 Do you think you can differentiate between the role of the artist and that of the curator, or do you agree with Boris Groys that there is no difference nowadays between art’s production and its exhibition?08

AZ: I often act as a curator of sorts in my art projects, using the contemporary art exhibition as a medium. I apply a similar method to that of a mockumentary: I use the institutional conventions of exhibition-making to expose the assumptions on which it is based and that we usually take for granted. This is, in fact, what experimental museum curators did in the early years of the Soviet regime. For instance, they created sculptural installations bringing together historical objects from museum archives and props to illustrate the principles of historic materialism, for instance in the regional Museums of Revolution or in the Museums of Atheism across the USSR. For them, the distinction between the copy and the original was unimportant, insomuch as creativity was subordinated to an understanding of history as a scientific and overarching narrative. During the same period, in the 1920s, Soviet curators also began including texts and statistics in exhibition displays; in other words, they were already using media that are nowadays an integral part of the palette of critical art. This is the kind of curatorial work that interests me: the creation of narratives through the display of objects, images and texts in the gallery space; for me the curator should be like a movie director.

SF: The Era of Stagnation in the Soviet Union, which extended from the mid-1970s to the late 80s, seems to be a major reference for some of your work, such as Sdelai Sam (Do it Yourself, 2010), named after the homonymous soviet magazine on do-it yourself art that targeted amateur artists. Which aspects of this period inspire you?

AZ: This time of severe political repression, when almost all the undertakings of the 1960s had been discontinued, paradoxically saw the emergence of great art movements such as the Moscow conceptual school. In the late 1970s, one of the only answers to the everyday feeling of hopelessness and timelessness was to express oneself creatively. It was during that period that workers’ amateur creativity flourished, exemplified in techniques such as wood-carving, hammered ironwork or amateur furniture design. The strict division between work and leisure during the era of late socialism made this creativity possible. It was an extremely democratic art and this is what still inspires me today.

SF: In your recent installation Forthcoming Dawn (2012), realised on the occasion of the exhibition ‘The Way of Enthusiasts’ (Palazzo Tre Oci, Venice, 2012), you offered a free laundry service to the population of Giudecca Island. This installation was a part of a larger project that involved imagining an underground network of people united to liberate life from today’s pervasive imperative to be creative. Here you are once more questioning the border between art and life. Do you believe that such kind of participatory intervention could have a real impact in everyday life?

AZ: Forthcoming Dawn is the proposal of a future radical political group that militates against the exploitation of human creativity. I have been telling everyone a story about what happened when the mother of my friend the theoretician Masha Chehonadskih applied for a factory job: she was asked to bring a CV and a creative representation of her labour skills. It turns out that the slogan ‘everyone is an artist’, which used to carry a liberating impulse, has turned into an obligation. If you want to work at a factory, be creative or we don’t need you! So in order to be free nowadays perhaps we’d rather learn creatively how not to be artists!

Footnotes

-

For more information on the work of Arseny Zhilyaev, see http://www.zhilyaev.vcsi.ru/

-

The exhibition ‘The Archive of the Future Museum of History’, devised by the participants to ‘The Pedagogical Poem’, together with Arseny Zhilyaev and Ilya Budraitskis, is on view at the Presnya Historical Memorial Museum from 6 November 2012 until 6 January 2013. For more information, see http://www.v-a-c.ru/files/pdfs/269/press%20release.pdf

-

For more information on the May Congress, see http://www.facebook.com/may.congress

-

From the Stalin’s decree ‘On the Reconstruction of Literary and Art Organizations’, 1932 in Helen Rappaport, Joseph Stalin : A Biographical Companion , Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 1999

-

The Occupy Abbay Manifesto was written by the people who took part in the General Assembly in the Moscow Occupy Camp and included anti-Putin claims, various social demands and defended self-organisation and direct democracy.

-

In one of his curatorial projects, Machine and Natasha (2009), Zhilyaev invited several russian artists to reflect on the fate of machines in a closed paper factory turned into an art cluster. For more information, see http://www.proektfabrika.ru/eng/events.php?id=46

-

Boris Groys, ‘Politics of Installation’, e-flux journal, no. 2, January 2009, available at http://worker01.e-flux.com/pdf/article_31.pdf