Chloe Ting: Your show at Chisenhale Gallery in London titled ‘In Cascades’ opened in June 2023.01 Could you talk about the development of this exhibition? How did it come about at this very moment in time in relation to your body of work?

Lotus L. Kang: There isn’t a distinct break between any of my projects. Rather, it’s one ongoing, fraying thread or vein. While there might be explorations of new materials, objects and forms, the work transmutes through adding or subtracting from what came before. It’s a very sedimentary kind of process, or a sticky process. The title of the show – ‘In Cascades’ – speaks specifically to this idea. It was co-commissioned by Chisenhale and the Contemporary Art Gallery in Vancouver, where another iteration of the work will be exhibited in September.02

Amy Jones, the curator of the show at Chisenhale brought up the idea of cascades very early on during one of our visits when we were churning ideas, going through books, photos, texts and materials. I was thinking about inheritance and epigenetics, memory, time and the body as forms of sedimentation. Of course, ‘cascades’ refer to bodies of flowing water. Our organism is also comprised mostly of water, so we’re closely tied to this element, and to water around us, whether in other bodies or planetary bodies of water.

In biochemistry, cascades refer to transmissions occurring at the cellular level, wherein the path of signals always carries traces and implications of the past or prior signals, affecting the chain of signals as it continues. Both the watery cascade and biochemical cascade bring up ideas of relation and interconnectivity, time, or past,

in which present and future are contingent.

This very much relates to my practice at large, although projects take place in different sites. It’s continually cascading, or as Octavia E. Butler writes, ‘All that you touch. You change. All that you change. Changes you.’03

The main piece in ‘In Cascades’ is an expansion from a series of works that I have been exploring since 2017 and that I call Membranes. Membranes point to a border or a limit, whether geographic borders or the bodily borders of skin, as permeable and porous. The Membrane works use construction materials, often pliable and left raw, alongside unfixed photographic films and paper that create embodied images which carry traces of the spaces where they were ‘tanned’ and exhibited, including traces of their inhabitants. They are in perpetual development and continually respond to light and the environment. A question I’m asking with these works is, what happens when the membrane itself is sensitive, selective, affecting what it holds, as well as what moves through it?

On another level, I have always been and remain interested in the play between verticality and horizontality, and how you make a viewer’s body implicated in your work when you have to crouch low to the ground. It can push against ideas of monumentality. Horizontality makes us think about the act of looking down and the act of looking up. With this new commission I wanted to expand from the vertical structures of the Membranes to an immersive structure that emphasises both horizontality and verticality. I found a type of joist that is full of holes, which points to voids, vessels and fissures; they were used to build out a horizontal scaffold or ceiling suspended above the viewer. There are also floor-based sculptures that use tatami mats alongside various cast objects and materials, and photographs documenting a ritual-performance I enacted leading up to the exhibition that exist in the folds of the mattresses and remain unseen, at least in the show. I wanted to create a ghostly architecture, with the film cascading down from the scaffold vertically; the things that are seen, or left unseen; the spaces that are visible and invisible.

CT: How does the consideration of the audience come about in the creation and exhibition of your work? I know, for example, your 35 photograms installation Her Own Devices (2020) was made as a gift for yourself. How do you consider who you’re making the artworks for and how does an external person encounter them?

LLK: In some ways, I have to forget the viewer because it helps give more space and permission for what I think of as a ‘soupy’ space, or being ‘in the mud’. Part of my making is to dwell on questions such as ‘what is this, even?’, ‘why am I doing this, even?’ – questions that often follow intuitive actions or gestures. As soon as I start thinking about a viewer, I will stop the process of the object or material clarifying itself to me. It becomes about how it is perceived by others. At that actual point when the work is still in the mud, I feel I have to nurture this latent phase to be able to see clearly – you can’t see the work when it’s still in the mud, and if you try that stops something in the work’s own becoming.

When I’m installing work in a gallery, I begin to think about the body in space. I’m constantly considering every angle and entry point that confronts or doesn’t confront a viewer. How space engages the body, how the exhibition and the work change in relation to the body’s own movement. My work at Chisenhale in this sense is a suspension, it expands space, it is something you walk around and into. I also wanted to contribute to the informal archive, which is the gallery’s floor. As Amy Jones pointed out, the floor contains the history and traces of all the other artists, visitors and artworks that have been at Chisenhale. I wanted my work to contribute to this archive in a way, and for the viewer to be aware of the raw quality of works and materials that are ‘unfinished’.

CT: It makes sense that your work addresses the porous relationship between the external environment and the human bodies. The space we are in could be affected by, on the one hand, political and affective forces, and also, on the other, by natural phenomena and entities like light and bacteria. How does your own porosity come into the picture?

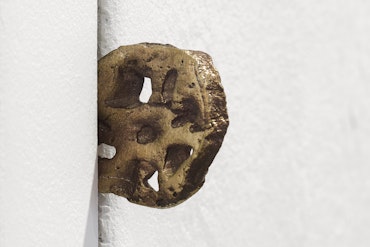

LLK: There is definitely my own porosity to place as I’m installing, and it always comes as a surprise. I guess it’s about being present in the space and seeing what unfolds from there – that’s a kind of porosity. Working with natural light at Chisenhale took a lot of consideration. Often London is grey. Since the show was on view during the summer we could get natural light for a longer period of time. The gallery recently opened the windows, which are beautiful but sit at an odd height, 2.7 metres or so above the floor so you can’t look out of them like you would a typical window. It is also by a canal, which makes the space damp, and so the environment creates a moodiness in the space. When I’m planning my site-responsive exhibitions, I don’t think just about the gallery space but also the spaces beyond. There’s a work in the show, Tract II, which was made on site in relation to this idea. It’s a chime of cast anchovies, hung on the exterior of the window; most people would miss it. You can see it blowing in the wind; if you were outside and close by you could hear it, but of course in the gallery it’s inaudible.

The gallery’s proximity to the canal means there is a likelihood of encountering rats. Sticky Pup I–IV, four rat pup sculptures cast in glass, are installed at the edges of the gallery, in the margins, close to the canal. They hold multiple meanings. They tend to incite a dual instinct of both tenderness and disgust in the viewer; a cute object that evokes both the need to care for it and the desire to destroy it. There’s also a legacy of equating racialised people with animals, so they become a figure to think about the racialised human animal. Initially though, the catalyst behind the sculptures was an article by Martha Kenney, co-written with her peer Ruth Müller, ‘Of rats and women: Narratives of motherhood in environmental epigenetics’.04 I read the article that spurred this investigation when I was living in New York, which is very much a city of rats. So many campaigns have been created to eradicate rats, such as Eric Adams’s mission to hire a ‘rat czar’. Meanwhile other campaigns persuade us that coyotes are our kin. It’s impossible to separate rats from the infrastructure of cities like New York: their proliferation is a direct result of human behaviour and movement. I thought about the inevitable contact we have to make with each other, and how we might imagine co-existence. Rats are used in science labs because we have much in common with them physiologically and viscerally, so our human-centric relationship to them is selective. How do we declare what is parasite and what is kin? So many parasitical figures are often also incredibly resilient.

-

Lotus L. Kang, In Cascades, 2023. Installation view, Chisenhale Gallery, London, 2 June – 30 July 2023. Photograph: Andy Keate -

Lotus L. Kang, Sticky Pup II, 2023. Photograph: Andy Keate -

Lotus L. Kang, Sticky Pup I, 2023. Photograph: Andy Keate

CT: Indeed. Who decides what is parasitical and what is kin? Can you tell me more about your interest and research in thinking through these two relationships? For example, you worked with cordyceps in Mother (2019–20) and Bloom (2019). Cordyceps are parasitic: they drain their host completely of nutrients before filling their body with spores that will let the fungus reproduce. At the same time, to humans, cordyceps can stimulate immunity and cell production and are thought to help fight cancer cells.

LLK: The figure of the parasite is emblematic of a body in the world: there is no body without the detriment of another body. It’s an acknowledgement of the volatility of being a body. I’m interested in parasitical figures because they don’t deny a material reality, but embody instead an earthly insistence. As a method for making, I’m not interested in reiterative representation, but rather in what it means to parasitise identity and what might bloom out of that process. I think of it as a regurgitation; that I am, as a body, a series of inheritances both physical and spiritual, but these inheritances are also embodied, regurgitated, translated through me. Same and different. And always folding in new layers.

For example, an ancestral regurgitation or parasitisation involves my paternal grandmother who was from North Korea but fled to the South on foot with her children before the war, and eventually immigrated to Canada. While I’m not interested in making this biographical detail transparent in my work, this migratory background has come to illuminate my own understanding and attitude towards provisional, unfixed materials that can be packed and unpacked, unfurling in differing, modular ways. When my grandmother moved to Canada, she worked as a worm picker; so, there’s also a passed-on familiarity with the horizontal, the low, the mud, the worm.

CT: We tend to set clear boundaries between whether a relationship is parasitic or symbiotic, but in fact relationships are often dynamic and this is reflected in how all natural systems work. It’s impossible for a stable system to exist without negative interactions as part of the picture. At the same time, nothing is independent from each other. As with all studies of life – zoology, botany, mycology – it is clear how dependent they are on each other. Especially the idea that some parasitic fungi depend on the living host’s cell to complete life cycles. This symbiotic relationship can sometimes be portrayed as one-host-one-fungus, but in reality, it’s always actually a network.

LLK: Donna J. Haraway says ‘we are compost, not posthuman’05 – we become with each other, compose and decompose.

CT: Exactly. And in this regard, I’d like to ask you about the points of explorations of time in your work: your exploration of generational stories, nature’s cyclical time, and the practical time required for your materials to develop and ferment. Can you speak more about how time plays a part in your practice?

LLK: The time it takes to make an artwork is a consideration, of course. There is time you can trace in the work, materially – how long this or that part took. But I’m most interested in illegible or invisible time. The time it takes to create encounters, material encounters. The time around the actual ‘making’, which in my practice occupies a lot of space and goes back to the idea of ‘mud time’.

I also think about time as cycles, but more similar to a cascade. A cycle that integrates the past and turns into a new cycle – it’s never the same. Maybe it’s not even a cycle. I wonder if there is a shape apt to describe it.

CT: Maybe a spiral.

LLK: Yes, it spirals inwards and outwards. I think about how time is indexed on the body both legibly and illegibly. Obviously as we age, time shows on our bodies. But it also does so in a way that may not be outwardly visible – a past event, events generally, or people that mark and change us at a chemical, or epigenetic level. This is also where my interest in Chinese Medicine and acupuncture developed, which seeks to understand the body as a web of both internal and external phenomena, so as to find the root cause of any issue rather than simply working with what’s visible. The root is often things that are less articulable, less tangible, less legible.

CT: What you’re saying reminds me of the study of genealogy through the idea of Sankofa. Sankofa is an Akan Twi word that means ‘to retrieve’. It is captured by a Ghanaian Adinkra bird symbol, with its head turned backwards, and its feet forwards. It signifies revisiting one’s roots and knowledge of the past, in order to move forward. I thought that was very similar to your way of thinking of cascades, time and personal histories.

LLK: I’ve never felt fully Korean, I definitely don’t feel Canadian, and now I live in New York. I never have a sense of real belonging to one culture or another and I think this is a common experience for many diasporic people. I have often pursued a desire to find or fill the holes in my familial histories, but what happens when my history doesn’t allow me to find anything? There aren’t many stories in my family, but lots of forgetting or not knowing. Sometimes it has felt like a kind of a failure on my end. If this is part of my research, then am I failing as a researcher? I don’t think I can find my identity by plucking one thing that I find interesting in Korean culture, or that I have resonance with. It needs to come from a webbier place. Similar to the root and the intangible, my work often becomes a site of indexing that process of uprooting through poetics and, to borrow Trinh T. Minh-Ha’s expression, for ‘speaking nearby’ rather than through a narrative storytelling. I now feel like I am working with, not a bag full of stories or a bag full of holes, but the hole itself as a figure that can be empty and full. I’m working with the lack.

Regarding personal histories, and back to the parasite – to parasitise one’s identity is also to betray your inheritances. I’m not bound to my history or biography as an artist; I can be both true and untrue to it. This agency is important.

CT: This thinking and researching through a personal-political, embodied archive tests the relationships between art and research, as well as the disciplines and even forms imbricated in structures of power. The existing pedagogical, institutional and academic structures function as relays of knowledge and power. And of course, so many of these structures permeate through what we consider meaningful artistic practices, and get to arbitrate what is considered ‘credible’.

Experiencing your work, and hearing about your practice, one can say that it is very much a process of research-creation. Research in materiality, in your own personal-political histories. I’m led to Haraway’s curiosity-bound eros, and how we can use this way of thinking in a research-creational approach, insisting on a multiplicity of responses, research, learning and understanding through what emerges from curiosity, and also from what is troubling and troublesome.

LLK: I don’t struggle to call my work intuitive because it is. If we think about the material realities of our body as informed by the past, a transmutation of the past, intuition isn’t just a feeling; it’s knowledge that we derived from these past experiences. We need to have a willingness to accept not knowing, and that ‘making sense’ might come after. Often, only after I make an artwork do I understand why I made it.

-

Lotus L. Kang, In Cascades, 2023. Installation view, Chisenhale Gallery, London, 2 June – 30 July 2023. Photograph: Andy Keate -

Lotus L. Kang, In Cascades, 2023. Installation view, Chisenhale Gallery, London, 2 June – 30 July 2023. Photograph: Andy Keate -

Lotus L. Kang, Lotus, 2023. Photograph: Andy Keate

CT: Many artists are now seeking a PhD in studio art. It is interesting to really consider what this means. There are discourses around distinguishing practice-based and research-led PhDs. The former is a form of investigation undertaken to gain new knowledge partly by means of practice and the outcomes of that practice; the latter focusses on research to advance knowledge about practice, or knowledge within practice – mostly through text. Both include practice as an integral part but the difference is in foregrounding practice or text.

You often speak about the relationship between text and your visual creation. The method is allowing the art to come first, and then your research or reading starts to contextualise and make sense of what you’re doing. At the same time, I think your talks as an artist, and the way you write about your art is also instrumental in understanding it. I want to hear more about how you navigate the relationship between the written and spoken language and your visual creation as expression.

LLK: That’s a really good question. It’s been a difficult and tense journey to get to a point where I feel comfortable sharing my thinking in language. I’m very passionate about nuance and I’ve always seen it in materials: they are doing the speaking. One day I’ll finally stop talking and just leave the materials list! I’m not a research-based artist where research is evidenced in the work,

or some didactic story is drawn out from it.

I have often been asked to be more specific and explicit about ideas of representation in the early stages of my making, but that was at a point when I didn’t even understand myself very well, so it didn’t feel right. It’s taken some time for me to get to a place where I felt I could bring my own thinking into the work and articulate that into written and spoken language. I find it torturous to write or speak, so my talks take several months to put together.

I also have to battle the resistance I feel to conceding to the desire of a consumptive audience who wants to understand, apprehend and essentialise me and my work. I’m an air sign so I tend towards non-fixity and letting ideas float and tangle endlessly rather than pinning them down. Writing for me can feel like a pinning down but perhaps that speaks more to my immaturity as a writer as I know language is so mutable. I’m working on it and I’m curious to see what my answer to this question might be in the future or how I might restructure a talk.

With my most recent talk, I had to be in a mindset that the written and spoken presentation of my work is not for the audience, but for my practice, as though my work could stretch out and extend itself. I’m not really explaining the work or telling stories around the exhibition making. I’m more speaking around it, grabbing one floating idea here, then another there.

CT: I could definitely feel from your talk that the intention of your writing was in service to your work. It wasn’t a description, or an explanation. It was giving context, a verbal or written life to your work. It feels like language is a tool that you’re using, whether it is text or visual.

LLK: Yes, for me the visual becomes the way in which I speak. I am often so in awe and envious of not just artists, but people who are incredible storytellers. I am not good at telling stories, and I think it is because I don’t have stories that were passed down to me. I never grew up with familial stories or around people who built narratives. My family emigrated abruptly from Korea and assimilated intensely into Canadian culture. I can’t speak for my parents, but from my perspective, there was a rupture in our personal stories. For me, it all feels like parts and debris, and I’m parsing through them. I am drawn to material in part because of this: it isn’t confined to a language. Through materiality, I put together a kind of story.

CT: It reminds me of the idea that, ‘There is no mother tongue, only a power takeover by a dominant language within a political multiplicity.’06The idea of the ‘mother tongue’ is very much linked to the birth of the modern nation-state. In A Thousand Plateaus, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari work around the idea of rhizome, a structure in which many points can connect to one another, but no location is the beginning or end. They argue that it’s about assemblages and multiplicities. This brings it very nicely back to your exploration of genealogy – there is no linear root and branch for you to trace. You use materials to assemble a story that you can’t put into or explain through clear language.

It also resonates with my own thinking around illiteracy, which I haven’t yet found a way to fully explore but that is connected in particular to the fact that my grandmother is illiterate. This is probably not uncommon especially for a woman in the Chinese context of that generation. But the treatment of someone who is illiterate, and all the repercussions of the inability to self-express in a society that is shaped by language and communication is something I’m interested in dwelling on. Of course, there are also discourses about post-literate worlds; Susan Sontag sees it as a visual one, whereas media theorists look at it through the development of technology.

LLK: I think whenever there is a limitation or hierarchy, whether it’s literacy or legibility as an artist, it forces a kind of resilience and adaptiveness. I’m curious with your grandmother, if she found ways to be nuanced that weren’t tied to literacy.

CT: Yes, in terms of practice, she spends a lot of time doing Tai Chi and hiking. So, she also ended up using the body, exercising herself in a different way not through text or language.

LLK: That’s amazing. The language of the body doesn’t have to be tied to linguistics. It makes me think about your earlier question on how I think about viewers in relation to my work. I want the viewers to find a way to experience the space and navigate through material with their body, hoping they can engage with a more internal, less articulate part of themselves. But I can see how that is a lot to expect of people, some might not want to go there. They just want an explanation of what they’re seeing.

CT: If you can use words to explain what you just experienced, or what you just saw, then it is solidified. If you can’t use words to explain then it didn’t happen, or it doesn’t exist.

LLK: Yes, a lot of art writing ends up being explanations. I really appreciate you sensing into my work in this way. I hope there can be more space for this.

Footnotes

-

Lotus L. Kang, ‘In Cascades’, Chisenhale Gallery, London, 2 June – 30 July 2023.

-

L.L. Kang, ‘In Cascades’, Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver, 29 September 2023 – 7 January 2023.

-

Octavia E. Butler, Parable of the Talents, New York: Grand Central Publishing, 2000.

-

Martha Kenney and Ruth Müller, ‘Of rats and women: Narratives of motherhood in environmental epigenetics’, BioSocieties, no.12, 2017, pp.23–46.

-

Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016, p.97.

-

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus (trans. Brian Massumi), Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1987, pp.7–8.