Wednesday

From inside the house, the world appears an obscured and tattered image of reality, breaking down rapidly towards the dissolution of everything we have assumed up until now to be the basis of our very humanity. We are living life through the screens of our computers and cell phones, screens more obbtrusive and more oppressive than ever before, yet at the same time so natural. I am obliged to deal with encounters in a virtual void, free of any concrete sensation, which appears to exist outside of familiar concepts such as time and space. It is as if my conscience has become separated from my body.

Monday

Ever since my life was overwhelmed by this extended violence, the works of art I consider in this section of Afterall have resonated like a distant memory. I did not seek them, they sought me. A short time ago I became a contributing editor for the journal, and when I was given the task of writing an essay, I thought it might be worth reflecting on these apparitions of works that come suddenly to mind, unannounced and at different times, sparking an interest in their history and leaving lasting and disturbing traces in their wake. Given the constant stream of such apparitions, it has proven not only impractical, but also disloyal, to group them in an essay, hence my recourse to a diary.

Before Yesterday

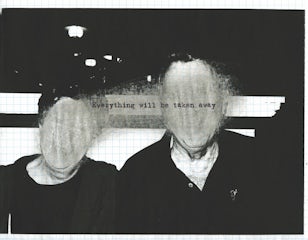

The first of these works is by Adrian Piper, a conceptual artist and analytic philosopher who appeared on the art scene in 1960s New York and continues working to this day. Although she is widely known, I was slow to get to know her, and my first contact with her work was via the essay ‘The Triple Negation of Colored Women Artists’. 01 The truly radical unease that I felt on reading this essay has continued to echo over the years. Piper’s innovative practices are expressed through many means – performances, public interventions, painting, sculpture, photography and more. Piper dares to challenge atavistic attitudes to race and gender, pointing out contradictions as a means of highlighting their critical social dimensions.

The particular work that keeps recurring for me is a photograph of two people in which the faces are blotted out. When I came to write this text, I could vividly recall the form but not the title. In my search I found the title within Everything (2003–ongoing), a series by Piper in which ‘Everything will be taken away’ is printed across various different images and later blackboards, mirrors and installations. 02 The phrase is inspired by a now well-known quote from Russian writer and intellectual Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s The First Circle (1968): ‘Once you have taken everything away from a man, he is no longer in your power. He is free.’

The precise image I had been thinking of was Everything, #2.8 (2003), a photograph of a couple photocopied onto graph paper and sanded down to erase their faces. Only the upper bodies remain, inhabited and animated by the disturbing words mentioned above. This was only the beginning; later, everything would be displaced, even without being moved.

Tuesday

In the midst of this crisis – far from unprecedented, despite appearances and prevailing opinion – I reread the book Kindredby Octavia E. Butler, 03

inspired by a text written by the artist Jota Mombaça that I once edited for publication. The past that is visited in that novel by its heroine, Dana, and which abruptly interrupts the novel’s ‘present’, was as vivid and real as I felt at that moment.

Friday

Every morning brings something new. Shocks as sudden as they are short-lived. What is scandalous appears mere sensationalism. The average time spent connected to the internet, in ‘networking’ and virtual ‘conferencing’ is reaching absurd levels; all ‘part of the job’. To reject this is almost to cease to exist: one’s presence in the ‘cemetery of the living’ has become compulsory. 04

During the first of many blows to shake Brazil I recalled a roadside slogan that had been widely publicised on social media in 2016: ‘Não pense em crise, trabalhe’ (‘Don’t think of crisis, work’), it said.

Wednesday

I suddenly remember Emilia Viotti da Costa, a Brazilian historian I deeply admire, who announces in one of her books that crises are moments of truth. I go after the full quote, which is as follows:

Crises are moments of truth. They bring to light conflicts that in daily life are buried beneath the rules and routines of social protocols, beneath the gestures that people make automatically without thinking about their meanings and realities. In such moments the contradictions that lay behind the rhetoric of hegemony, consensus and social harmony are exposed. 05

Saturday

The text by Jota is finally online.

Dana Franklin is the protagonist of the novel Kindred (1979), by Afro-American science-fiction writer Octavia Butler (1947–2006). […] Dana is dragged into the past and therefore reinscribed in the historical scene of enslavement, for this is precisely the scene that inscribed not only Black life but also the integrity of the Modern Text – and its temporal dynamics – in a continuous cycle of expropriation and destruction of Blackness as a condition for the emergence of social life and the mundane.

Although Butler presents Dana’s experience as speculative fiction, it does not seem pointless to me to ask the Black reader if, once confronted with the perspective of a Black body leaping into the past and thus having to reinhabit the political territory of a slave plantation, it is not possible to find a nexus between this narrative and our own life narratives. 06

Yesterday

In exile from time and space, I was almost at breaking point. During pauses in my daily routine I came across the writer Lima Barreto. O cemitério dos vivos (Cemetery of the Living), written from 1919 to 1920 when the writer was a psychiatric patient at the Hospital Nacional de Alienados in Rio de Janeiro, is comprised largely of autobiographical annotations that the author had intended to transform into a novel. His delusions, caused by a combination of alcohol and the material difficulties of his life, brought him to the attention of the police and mental health authorities. Reading the notes he made during this period of confinement made me question my own sanity.

There suddenly came upon me a horror of society and of life itself; a desire for complete annihilation, more than that brought by death; a desire for the total extinction of my memory on earth, a despair at having dreamed and thought such great things of myself, and now to see myself fall so low, from one moment to the next, without having in fact lost my position, that I almost burst into tears like a child. 07

Monday

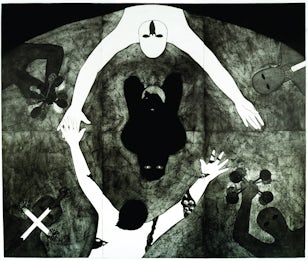

I have been morbid but have not avoided it. When I first discovered the work of Belkis Ayón I was fascinated by the way in which the artist dealt with death, and especially the cult of death08. Born in Havana, Cuba, Ayón died young but in her life produced an innovative phantasmagoric iconography of a fraternal secret society called Abakuá. I was attracted by the black tones in her engravings, produced by the technique of collography in which prints are combined to create narratives with a mixture of visibility and opacity, an effect reinforced by the choice of colours. Although an atheist, Ayón dedicated years of her life to portraying the history of these religious rituals in which women were prohibited from taking part, despite the fact that it had been a woman who had revealed the secret that lay at the very origin of the fraternity. According to myth, it was this act of revelation that had in fact led to women being banned from the cult. I like to think that the artist also revealed these secrets to me. The entire mystery is expressed in the eyes of the people she portrays: only the eyes, the windows of souls, are clearly defined, always looking directly at the observer. Everything else is somewhat vague, but the psychological dimensions of the characters add a considerable air of reality to the dialogue.

More forcibly than ever before, the end of life has been transformed into a perverse attraction, captured and proliferated in such an uncontrollable and unlimited manner as to turn violence into banality. The lack of differentiation between images, propagated in excess and dictated by the tyranny of visibility, dulls the senses and undermines values. It was this malaise that prompted me today to converse with the work of Ayón, filled with stories so real that they once more awaken the senses. The death led me to reconsider the quality of my time in the form of meditation.

Wednesday?

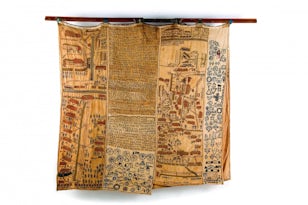

Eu preciso destas palavras. Escrita. (I need these words written down.) is the title of one of the banners made by the artist Arthur Bispo do Rosário, 09 produced at the Colônia Juliano Moreira, a psychiatric institution in Rio de Janeiro. Yet another person affected by racism under the guise of normopathy. It is said that Rosário introduced himself there saying, ‘one day I simply appeared!’. For me it seems that he really has this power. In situations such those happening now, where violence and control have been introjected as something normal, to be sane is also to be sick. I felt happy when I read the words the artist sewed into this banner, interwoven with his memories. Rosário’s world – a cell – was considerably limited, but through embroidery the artist was able to expand his space, weaving within it infinite possibilities. Thinking about this banner pulled me back from the brink of collapse.

Monday

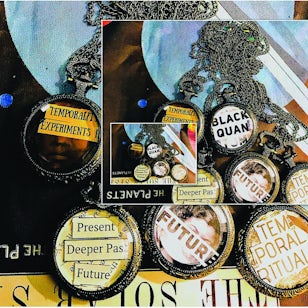

I feel the loss of the spatial and temporal dimensions of my body and my experience, lost in the lack of spatial and temporal references. How to deal with this absence, an unprecedented transformation compressing space and time? Wishing to add substance to the minutes, perhaps motivated by the feeling that the more that I do the further behind I am, I set the times of all of the objects in the house with a clock, and once again feel imprisoned. A little later ‘the temporal disruptors’ come to mind:

The Temporal Disruptors is a collection of watches re-crafted by Black Quantum Futurism to embody the temporal features of Black womxnist and Black quantum futurist time. The series is inspired by RAMM:ΣLL:ZΣΣ Time Stoppers watch series and by the contributions of Black women scientists and inventors. Each watch is paired with a key that can be used at a computer terminal to unlock sonic passageways, and accompanied by a mirror for use in conducting DIY Black womxnist temporal rituals. 10

Today

125,000 deaths in Brazil due to coronavirus and carelessness. In the city of São Paulo, where I live, the mortality rate is 60% greater among blacks.

Morning

‘Eu não estou aqui para arrumar as bagunças alheias. Eu não sou branca, não tenho nada a ver com essas desorganizações’. (I am not here to clear up other peoples’ mess. I am not white and I have nothing to do with this chaos). 11 I am always learning from Carolina Maria de Jesus, a tireless novelist with an impressive output. I have a collection of citations of her work that I would love to see in complete form. Perhaps it was because of this interest that today I came across news of the publication of all of her manuscripts.

Evening

‘Wait a minute’, he said. ‘I am not minimising the wrong that is being done here. I just…’

‘Yes you are. You don’t mean to, but you are.’ 12

This is a passage from Kindred. It sums up so many recent conversations.

Still yesterday

I returned to Lima Barreto, because the cover of his biography was illustrated by Dalton Paula, with whom I was speaking in a live stream.13We talked about official versions of history, and only then it struck me that Paula’s poetic vision might be taken as a commentary on the life of Barreto and his relationship with madness – something that tormented the author throughout his life, and ended up considerably influencing literary criticism of his work. Far from the world, without honours or horizon, books have been my most comforting company. They raise me up, and also lay me flat. Through them I am lifted far from popular tastes – a division of great interest to Paula and the theme of a series of questions raised in his work. These questions relate to the black population of the sertão (a semi-arid region of Northeast Brazil) and the artist’s knowledge of the landscape of this enormous country more generally. His 2016 series Cura (The Cure), is truly palliative as regards this conflict. Here, the covers of the books become guides to illustrate knowledge and use of plants in medicine, along with an assortment of folk healing practices. Scenes portraying cures are presented against blue-green backgrounds, and are reminiscent of ‘PhotoPainting’. This type of portraiture, which involves touching up photographs and even adding new elements such as details on clothes, was very popular in Brazil in the mid-twentieth century. The advent of new photographic technologies such as digital photography, popularised by mobile phones with digital cameras, has made this technique almost obsolete. I laid down the book to read these images instead.

Thursday

Sixty days of lockdown; it is cold and overcast. I woke up this morning thinking of a work by the artist Lorna Simpson. I had spent a long time looking at it during an exhibition-related search, but today it sank much deeper into me. It is called Five Day Forecast, dated 1991. Made up of a series of five photographs, it suggests a type of diary of daily life with little variation. There is almost no change in the poses of the subject, a faceless woman, but in each photograph her stance is tense. Below the pictures there are ten words, each beginning with ‘mis-’, which also suggest the title ‘Miss’ or ‘Ms’. Among such words are ‘misfunction’ and ‘misinformation’. Do their negative connotations imply a repeated collapse in time or a premonition?

Sunday

A thousand people a day and a perpetual present devoid of memories. It was mourning that led me to the Parede da memória(Memorial Wall) (1994/2015). This monumental work by Rosana Paulino is composed of numerous amulets, central to Afro-Brazilian cultural and religious iconography. Amulets are sacred objects meant to be carried on the body, but here they are ‘at the service of memory’. 14 A large set of small embroidered cushions are arranged side-by-side. Each is screen-printed with a photograph of one or several of the artist’s family members. The 3×4 cm size of the images are typical of family photographs, and here form a record that is both personal and collective, one with a broad and self-determined notion of individuality. The Parede da memóriaspeaks of presence and fills this otherwise empty time, even if it is with the feeling of loss that has to exist and be acknowledged. Let us hope that the feeling will act as an engine rather than a brake.

Tomorrow

I have already left the time and place in which I am writing this, but here are some jottings for a future essay.

Footnotes

-

Adrian Piper, ‘A tripla negação de artistas mulheres de cor’, in Amanda Carneiro, André Mesquita and Adriano Pedrosa (ed.) Afro-Atlantic Histories, Vol.2 (exh. anthology), São Paulo: MASP Publishing, 2018, p.624.

-

For these studies and other material and information about the artist, see http://www.adrianpiper.com(last accessed on 16 September 2020).

-

For these studies and other material and information about the artist, see http://www.adrianpiper.com(last accessed on 16 September 2020).

-

Octavia E. Butler, Kindred: A Novel, Doubleday [1979] (trans. Carolina Caires Coelho), São Paulo: Morro Branco, 2017, pp.162–63.

-

Cemitério Dos Vivos refers to Brazilian author Lima Barreto, Diário do hospício & O cemitério dos vivos, São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2017, p.256.

-

Emilia Viotti da Costa, Crowns of Glory, Tears of Blood, The Demerara Slave Rebellion of 1823, New York: Oxford University Press, (trans. Anna Olga de Barros Barreto), São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1998, p.13.

-

Jota Mombaça, ‘The Cognitive Plantation’, part of ‘Art and Decolonization’ [online project], Museu de Arte de São Paulo, 2020 available at https://masp.org.br/uploads/temp/temp-xnq24GTNVnjHIfrh0Ktm.pdf (last accessed on 16 September 2020).

-

See L. Barreto, Diário do hospício, op. cit. p.256.

-

A collection of the artist’s work is part of the Museu Bispo do Rosário de Arte Contemporânea, situated in the buildings of the old Colônia Juliano Moreira, named after the artist in 2002. See http://museubispodorosario.com (last accessed on 16 September 2020).

-

El Museo del Barrio in New York dedicated a retrospective to the work of Belkis Ayón, ‘Nkame: A Retrospective of Cuban Printmaker Belkis Ayón’, curated by Cristina Vive, 13 June – 5 November, 2017. Some works were also exhibited at the 10th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, ‘We don’t need another hero’, curated by Gabi Ngcobo with Nomaduma Rosa Masilela, Serubiri Moses, Thiago de Paula Souza and Yvette Mutumba, 9 June – 9 September 2018. The artist’s website shows other engravings in this series, available at http://www.ayonbelkis.cult.cu/en/home/ (last accessed on 16 September 2020).

-

A collection of the artist’s work is part of the Museu Bispo do Rosário de Arte Contemporânea, situated in the buildings of the old Colônia Juliano Moreira, named after the artist in 2002. See http://museubispodorosario.com (last accessed on 16 September 2020).

-

Black Quantum Futurism is an interdisciplinary artistic collective formed by Rasheedah Phillips and Camae Ayewa, dedicated to black futurist reflections on space and time, exploring intersections of imagination, fiction, creative media and activism, with a focus on recuperation and preservation of memories and histories of marginalised communities. See https://www.blackquantumfuturism.com(last accessed on 16 September 2020). For the text on ‘temporal disruptors’, see https://www.picuki. com/tag/blackwomxntemporal (last accessed on 16 September 2020).

-

Lilia Moritz Schwarz, Lima Barreto: triste visionário, São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2017.

-

Amanda Carneiro and Rosana Paulino, The Sewing of Memory, Terremoto, México, 14 February, 2019, available at https://terremoto.mx/tag/amanda- carneiro/ (last accessed on 16 September 2020).