Context and Creation of the Taller de Gráfica Popular

The Taller de Gráfica Popular (Popular Graphics Workshop, henceforth the TGP) was founded in 1937 in Mexico City by the artists Leopoldo Méndez, Luis Arenal and Pablo O’Higgins. As its name indicates, the group focussed on printmaking and functioned as a workers’ organisation. The activity of this space was structured around specific political processes and conjunctures, while at the same time conceiving art as part of ‘popular culture’, evident in their production methods. The definition of the workshop in political terms allows us to understand its approaches and artistic decisions as delineated by their position with regards to a series of national and international historical events. Indeed, the historical context of the founding of the TGP is situated between the development of the Spanish Civil War and the advent of World War II. Initially, the TGP operated under the conditions imposed by ‘committed art’ that linked the local realist project (not exclusively that of the Soviet Union) to the tactics promoted by the Popular Front.01 Some of the recurring themes in this initial period include the support for Republican Spain, anti-fascist rhetoric and the condemnation of the invasion of the USSR by Nazi troops. On the other hand, under a complex and sometimes contradictory negotiation, the workshop was close to programmes of the consolidating post-revolutionary state, especially those related to the educational, health and ethnographic branches. 02 Additionally, despite advocating separation from party politics, they occasionally were involved in specific campaigns and projects. 03

The exhibition presented by Pilar García and James Oles, ‘Gritos desde el archivo’ (‘Screams from the Archive’, 2008), organised through the TGP fund of the Academy of Arts, systematised the topics of the workshop by recognising the iconography and visual repertoire created by a group completed by Ángel Bracho, Isidoro Ocampo, Alfredo Zalce, Ignacio Aguirre, Francisco Mora and Hannes Meyer in the 1940s;04 and by Raúl Anguiano, Elizabeth Cattlet, Mariana Yampolsky, Fanny Rabel, Óscar Frías and Roberto Berdecio in the 1950s.05 The selection of works presented in the exhibition emphasised two operational themes: those aspects linked to international politics, which functioned as a universal code (fascism, the swastika, the soldier, horses); as well as the rhetoric and symbols linked to local politics, in the context of the governments of Lázaro Cárdenas (1934–40) and Manuel Ávila Camacho (1940–44), which correspond to the years of creation and consolidation of the workshop (school constructions, the city, the press and the workers).06

The relevance of the TGP as a political organisation is perceptible in how the space received exiled artists such as Meyer and Berdecio or women producers and also migrants like Catlett, Yampolsky, Rabel and Templeton. From the beginning, the statutes of the TGP were based on the transnational perspective and the networks of solidarity, which were organised with references to the Popular Front and under the motto of international support. The publication Muerte al invasor (Death to the Invader, 1942) – written by Ilya Ehrenburg, illustrated by the Republican artists Miguel Prieto and Josep Renau, and edited by Hannes Meyer – exemplifies the flexibility of the TGP’s language, and how this written and visual narrative functioned at the same time in national and international contexts. This war chronicle adjoined a series of ‘emergency images’07: Mexican graphics (Luis Arenal, Gabriel Fernández Ledesma, Leopoldo Méndez, Xavier Guerrero and Francisco Mora); Soviet propaganda (Okna Tass); German artists against the Nazi regime (Karl Schwesig) and recontextualised works of Goya, Daumier and José Guadalupe Posada.

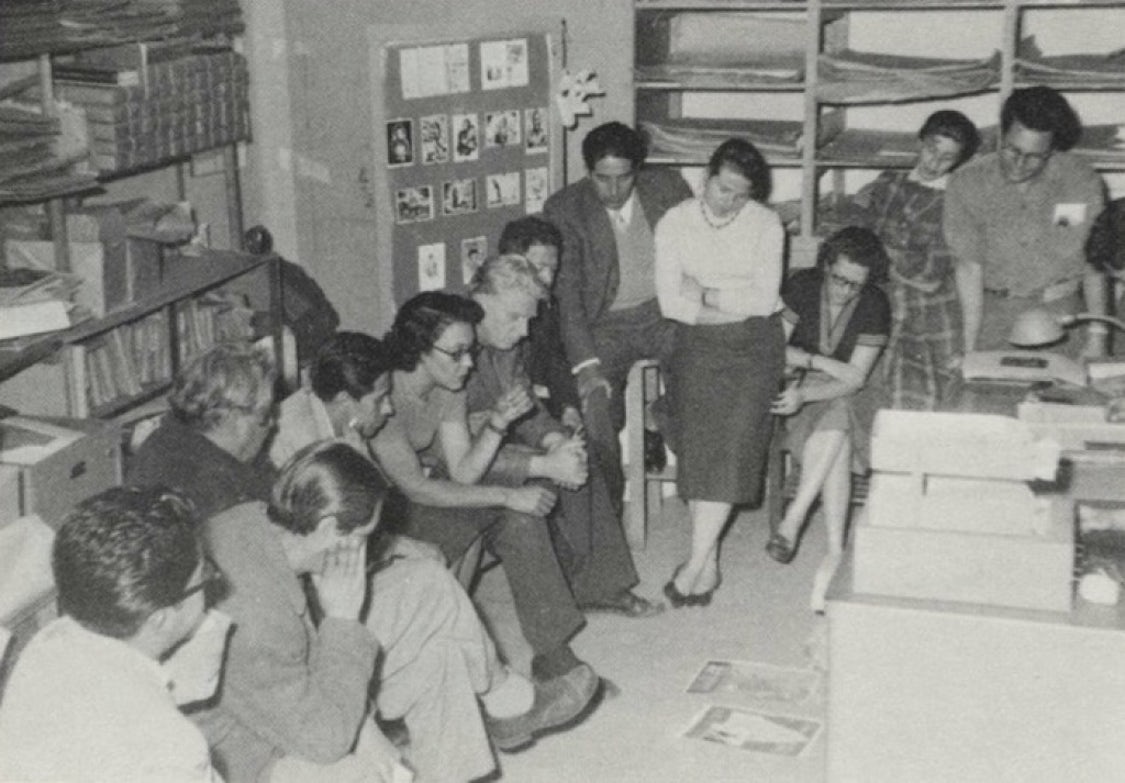

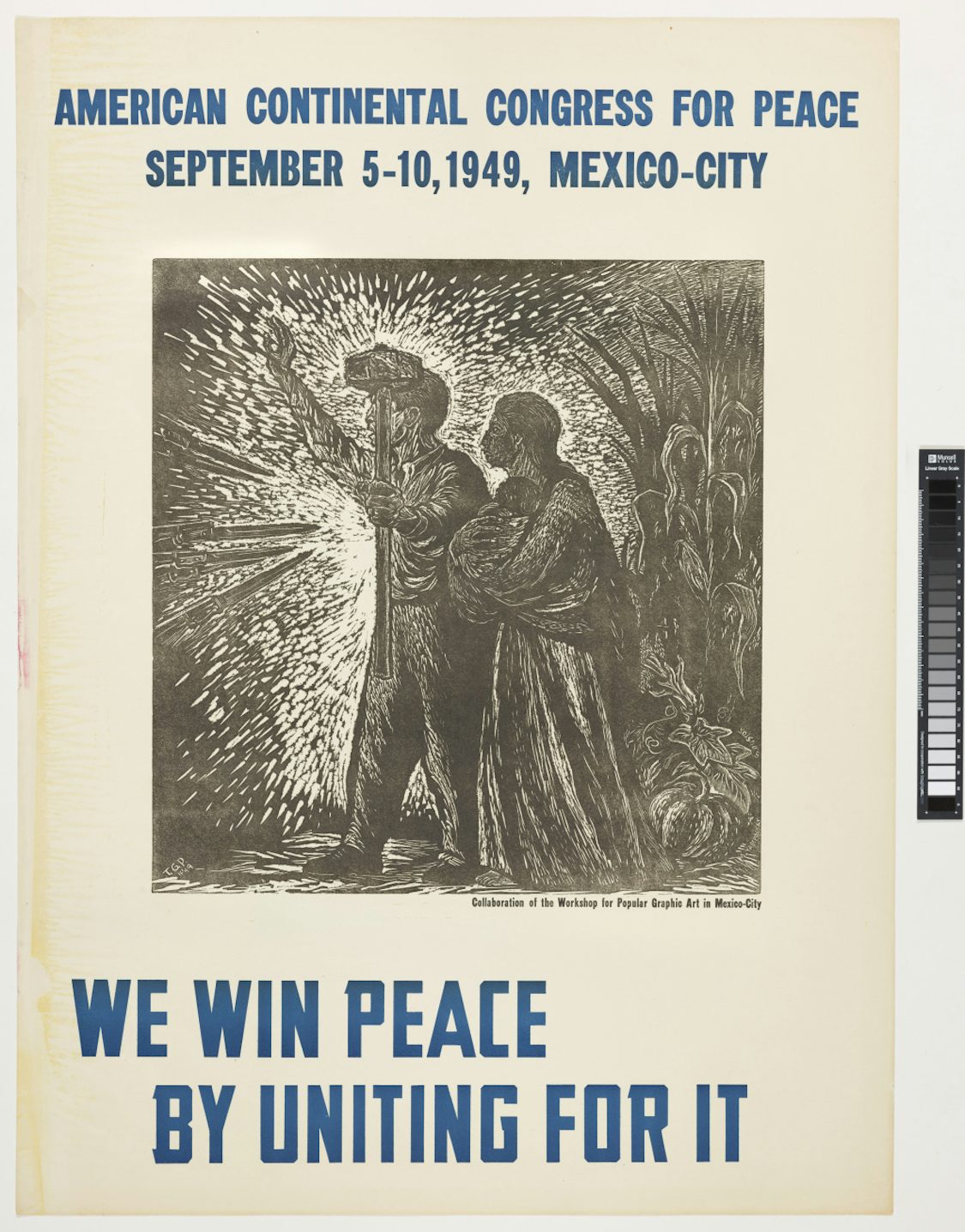

The Congress for Peace (1949), held in Mexico City, represents one moment in the itinerary of the TGP’s international exhibitions amid post-War ideological disputes; the TGP collaborated with works that activated the political imaginary of realism in negotiation with the USSR’s rhetoric of nuclear disarmament and the Dove of Peace. Decades later, also in line with the Partido Comunista Mexicano (PCM), the support of a TGP led by Celia Calderón, Elizabeth Catlett and Mercedes Quevedo, was brought to the founding of the National Union of Mexican Women (Unión Nacional de Mujeres Mexicanas, UNMM) in 1964. This act is evidence of the TGP’s basis of adaptation, flexibility and renovation in accordance with new struggles (revolutionary movements and national liberation in Latin America and the triumph of the Cuban revolution), and with the development of feminism in Mexico. The TGP was fundamental to the visibility of the UNMM:

We achieved a large audience since women from the Taller de la Gráfica Popular such as Elvira Gazcón, Adela Gómez, even later Fanny Rabel, some great women artists who fed the Union to make the appeal to the rest of the people and we worked with peasant women, with working women, with people from urban areas. 08

An exhaustive analysis of the TGP would offer an alternative narrative to that of traditional art historiography since, due to its long duration, it acts as an intermediate project between the early avant-garde and the post-avant-garde. 09 This text, however, is only an initial overview of the history of the TGP. It focusses on the forms of organisation and material/technical sustenance that shaped the workshop’s programme to highlight elements such as collective organisation and the valorisation of popular culture. It presents the foundations of a political-aesthetic practice based on popular printed matter and the reconsideration of the portable mural,10 approaches that make possible a history of art that exceeds both national borders (if we think of Chicano graphic art) and traditional formats. 11

The Workshop

Historian and curator Francisco Reyes Palma has extensively studied the precursors of the TGP, exploring the organisations and publications that preceded this programme to understand the development of a space dedicated to debate and graphic production.12 Focussed on the 1920s, he has highlighted the foundation of the Sindicato de Obreros Técnicos, Pintores, Escultores y Grabadores Revolucionarios de México (Union of Technical Workers, Painters, Sculptors and Revolutionary Engravers of Mexico, 1924) and the publication El Machete, conceived by this same organisation, quickly absorbed by the Partido Comunista Mexicano (Mexican Communist Party, PCM). Following this process, Reyes Palma explains how writer Juan de la Cabada and artists David Alfaro Siqueiros, Leopoldo Méndez and Pablo O’Higgins founded the Lucha Intelectual Proletaria (Proletarian Intellectual Struggle, LIP) and the edition Llamada (The Call’, 1931), with only one issue and a brief history, due to the political prosecution of its founders.13For Reyes Palma, the LIP was decisive for the organisation of the League of Revolutionary Writers and Artists (LEAR), in 1937, under the direction of Luis Arenal, who, in turn, was part of the Siqueiros Experimental Workshop of New York (1936), which originated from the dialogue between the Mexican muralist and the Communist Party of New York. 14 The founding of the Taller de Gráfica Popular coincided with the closure of LEAR in 1938. Reyes Palma indicates that the reasons for LEAR’s failure included economic difficulties, links to the official cultural and educational project, and the constant interventions of the Communist International. It was against this historical backdrop that three of the most important members of the association, Méndez, O’Higgins and Arenal, proposed the organisation of the TGP.

Reyes Palma’s emphasis on Siqueiros and Arenal is noteworthy. Indeed, Siqueiros supported and encouraged many of the actions of the TPG, based on his previous work with the Block of Mural Painters and, to a greater extent, in the Siqueiros Experimental Workshop. In 1936, when Siqueiros travelled to New York, he redefined the expectations of his artistic production. To do this, he established direct connections with reformist trade unions and maintained links with various workers’ organisations in the United States.15 Many of the documents describing the work of the New York collective are devoted to the organisation of a painting workshop-laboratory, which resembled the operation of a factory. The texts describing the collective’s activity consist of stock/requirement lists, the cost of materials, signage of activities and the cooperative divisions of profits. 16

Through these documents, it is clear how Siqueiros sought to appropriate the most emblematic techniques of 1930s Fordism. The technological-organisational dimension of the Siqueiros Experimental Workshop (teamwork, speed of production, creative innovation and including the consumer in the supply chain) within the Popular Front discourse, reaffirmed the effectiveness of a model constituted under new production teams or workshops, created primarily to produce propaganda capable of confronting the rising fascist aesthetics.

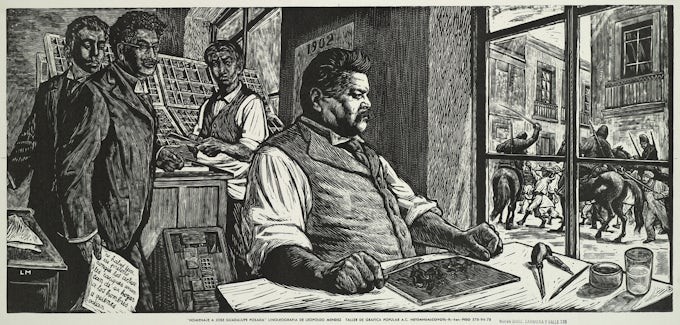

Art historian Deborah Caplow highlights the importance of collectivity in the formation of the TGP. Focussing on Leopoldo Méndez rather than David Alfaro Siqueiros, she explores another genealogy of the TGP, emphasising the organisation of the Escuelas de Pintura al Aire Libre y Centros Populares de Pintura (Open Air Painting Schools and Popular Painting Centres, 1923), Estridentismo (1921–27), LEAR (1933–38) and the TPG.17 The first genealogy proposed by Reyes Palma is the one that distinguishes the previous political references, the design and management of the workshop, and the relevance of Siqueiros and Arenal as participants in industrial work spaces.18 A second genealogy, suggested by Caplow, explores the avant-garde groups and looks for interrelations or origins in the Revolution (which is connected to the political lithographer José Guadalupe Posada). This argument underlines the links between political and artistic avant-garde, while highlighting the participation of Leopoldo Méndez as an illustrator of Estridentismo and participant in previous fronts, such as LEAR.19 Seen from this perspective, the TGP is the convergence of several avant-garde approaches, in which groups and collectivities play a prominent role.

The specific nominalist act to use ‘Taller de Gráfica Popular’ is also relevant, as it refers to questions of operation and conditions of material production. The workshop maintained forms of collective and pedagogical organisation, in accordance with Siqueiros’s experiences. However, it did not develop the same sense of mass production, but, through the use of linoleum and wood prints, established a tension between reproducibility and artisanal practice. The choice of the term taller (‘workshop’), sidestepping the League, the Front, the union and the cooperative, allowed them to distance themselves from the interventions of both the Communist Party of Mexico and the International Communist League, which had weakened LEAR. On the other hand, the workshop was a format that coincided with their technical and discursive expectations, since the objective of the TGP was more didactic (to distribute a message to the people) than dogmatic. The clauses for the foundation clarify these considerations:

This workshop is founded with the aim of stimulating graphic production for the benefit of the interests of the people of Mexico, and for that purpose it aims to gather a greater number of artists around a work of constant improvement, mainly through the method of collective production. 20

This sentence gave way to a list of statutes and duties of the workshop. These twelve points determined how production was to be carried out: both individual as well as collective authorship, a distribution of copies among the members, as well as quotas, profits, rules and regulations. The document also outlines the duties of a Steering Committee and of the General Assembly. These two bodies determined the workshop’s practical activity, negotiations and decisions, and gave shape to a model of equitable operation.

Popular Graphics and the Portable Mural: The Formation of the Popular Reader/Viewer

In 1954, the Mexican-Argentine critic Raquel Tibol published a series of debates around the TGP.21 The document describes the group’s modes of operation after seventeen years of activity. The 1950s marked a time of crisis for ‘revolutionary art’, which was faced with the post-War transformations of cultural policy and an imminent adaptation on the part of official art. 22 It was in this context that a ‘Graphic Assembly’ was held, dedicated to pointing out the economic problems of the workshop and various issues that had persisted throughout so many years of activity. Tibol proposed three guiding questions to analyse the group’s stagnation. She also pointed out, with the incisive tone that characterises this author, that the TGP, rather than working for the benefit of the people, ‘focused on illustrating the thinking of a political superstructure’. 23 That meeting allowed active members (Méndez, Rabel, Berdecio, Yampolsky, Bracho, Anguiano, Aguirre and Cattlet), to present a retrospective and analytical view of the TGP. The most prominent criticism emerging from this meeting concerned the insistence on the model of ‘art for the people’ and its thematic, didactic and technical orientation. The collective organisation under the conditions of the assembly and the economic crisis of the workshop were also discussed:

Fanny Rabel: First of all we have to point out that we are a group of people from the same tendency, we all want a socially useful form of graphic work.

Pablo O’Higgins: The strength of the TGP has been based on collective work. Our main interest is contact with the people and popular organizations. We would not achieve this without collective work, work that includes discussion, criticism, and self-criticism.

Rabel: The TGP is not subsidized by the government or patrons. To sustain it, the artists contribute their labor, their artistic works, and their money. Therefore, the TGP suffers from economic problems.24

Faced with these statements, the muralists Diego Rivera, Juan O’Gorman and David Alfaro Siqueiros each responded to the group and to their justifications and concerns. Rivera explained that an update was needed in the models of ‘production for the people’, through the recognition of renovated structures of work consequent with his proposal (low-cost sheets) and a variation in the information presented, more informative than epic (‘saying what is not said in any newspaper’).25 Siqueiros, for his part, insisted on understanding the social conditions, the technical modernisation and the political stagnation of the project: ‘the TGP can be modernised, it can be mechanised, it can produce a print of better quality and greater scope’. Finally, O’Gorman responded to the very language of the group and questioned the effectiveness of the message, highlighting the effectiveness of Posada’s satire against the ‘sadness’ expressed in the images of the workshop: ‘if the engravers of the TGP impregnated their criticism with mockery, that mockery that gives joy as well as a sense of strength, the people would look for their works.’26 The key to this polemic was undoubtedly based on how to understand the conditions of ‘lo popular’ and its relationship with art.

As Viviana Gelado explains, the valorisation of popular culture was a fundamental aspect in the formation of the avant-garde in Latin America. According to the author, the definition and uses of ‘the popular’ are the result of a conflict between the State, intellectuals and society, under ‘national and racial determinations’.27 In Mexico, the primary purpose for artists and intellectuals that defined the cultural policy of the Revolution was to study ‘expressions of the people’ as part of a nationalist programme.28 This modernisation project insisted on a racial and cultural homogenisation through the idea of mestizaje, as part of an idealisation of the ‘otherness’ inside of an imagined community.29 ‘Essence of the race’ was a recurrent articulation in the narratives and reinterpretations of a series of cultural and historical manifestations. These productions were incorporated (sometimes erased) into national repertoires as popular industries or folklore.30 A series of collections, museums, catalogues and magazines functioned as classification and exhibition apparatuses for these inventories. The TGP visual dictionary reaffirmed this racial configuration, considering the ambiguous references of the peasant, the indigenous and the proletarian as the principal characters of their epic images. 31

At the same time, the definition of the ‘popular’ implies a dialogue between the cultural industry and peripheral cultures.32Specifically, the TGP took up the tradition of popular prints and flyers produced at the beginning of the twentieth century. The use of the term ‘popular’ reaffirmed a usage common in the previous decade (specifically Posada’s work) and gave it new possibilities. For example, in Revistas de Revistas, Jean Charlot described Posada’s work in these terms: ‘He, through two thousand plates, almost all illustrations of corridos from the Venegas Arroyo house, created a genuinely Mexican printmaking, and he created it with such strong, such racial features, that it can be compared, for example, to the Gothic or Byzantine feeling.’33Diego Rivera, for his part, lauded the technique in a monograph dedicated to the printmaker by this same publisher:

A worker’s hand, armed with a steel burin, he wounded the metal with the aid of corrosive acid to throw the sharpest apostrophes against the exploiters. Precursor of Flores Magón, Zapata and Santanón, guerrilla, and heroic opposition newspapers. 34

Therefore, the uses of the ‘popular’ by the TGP affect both the production model and its distribution goals. That is to say, the formats chosen (posters, loose sheets, flyers) were significant choices that sought to take up the tradition of the popular prints of the early twentieth century, specifically that of Antonio Venegas Arroyo and José Guadalupe Posada. Recent studies dedicated to popular prints allow us to see these quotations in a new light, by understanding the history and relevance of popular prints and the uses of graphics.35 Thus, it is possible to assert that the choice of graphics by the TGP determined, in this way, a quest for the creation of a transient reader and spectator, a worker and not necessarily a literate one.

Popular prints stand out for being between two worlds (that of the written word and of the pictorial) and are considered hybrid assemblages: ‘The popular culture that is represented in print, by its diffusion and its production, is nourished by all sources regardless of their origin, whether from great or minor traditions.’ 36 The reception of these printed materials in times of the armed conflict, was varied, since they were read or sung out loud or simply passed from hand to hand. The constant themes of prints were religion, corridos and miscellaneous news, where disasters and catastrophes captured the public’s attention and drove their consumption. The work of Vanegas Arroyo and Posada falls into this second category, with the dissemination of news about the Revolution. These printed works are also known as cordel literature, that which is dedicated to reading in public spaces (squares and streets) and private spaces (neighbourhood rooms and patios). 37 For Enrique Flores, the production of Vanegas Arroyo and Posada should also be considered as popular press, a category that usually includes news booklets and anarchist political pamphlets: ‘Devotion and amusement, natural catastrophe and accidental disaster do not cease to have a deep political element in the popular imagination…’. 38

To conclude, it is worth emphasising that the approach to the uses of the popular by the Mexican avant-garde, as proposed by Viviana Gelado, allows us to understand why the figure of Posada was fundamental to the rhetoric of the TGP. This reference represents a continuity of the revalorisation of the printmaking tradition orchestrated by artists Jean Charlot and Diego Rivera, and others, within the framework of a broader study of the popular arts carried out since the 1920s. Both painters highlighted the critical work of the printmaker and the effectiveness of his messages during the revolutionary process. In an almost fictional way, they created a genealogy for ‘revolutionary art’ that sought to link Mexican Muralism (which also had aspirations of popular consumption) directly with Posada and Venegas’s printing press. Thus, knowledge of these popular prints shaped the claim made by Rivera, O’Gorman and Siqueiros to the TGP in 1954, as it responded to a pretension of actuality of a model in accordance with ‘popular consumption’ and the study of the means of production (grotesque aesthetics, relevant information, colourism, cheap production, simplicity of distribution).

It should be mentioned, however, that there was a relation between these muralists’ statements and the work of the TGP, a connection exemplified in a graphic by Alfredo Zalce. This simple image is an instruction manual for the transient mural. In this sort of meta-graphic titled Hoja popular ilustrada we can see a series of instructions arranged in boxes in the form of a syllabary. This illustration designed by means of vignettes shows different places and ways of distributing a flyer or poster. To a certain extent, such production coincides with the street uses of the mural broadsheets in Manuel Maples Arce’s Actual número 1 (1921), Prisma. Revista mural (1921–22) published by Norah and Jorge Luis Borges, Guillermo Juan, Eduardo González Lanuza and Guillermo de Torre, and the mural newspaper El Machete (1924), organised by the Sindicato de Obreros Técnicos, Pintores y Escultores y Grabadores Revolucionarios de México. In fact, this portable muralism was essential for the revival of the graphic project in the post-avant-garde, starting with what Raquel Tibol called ‘neográfica’ in the 1970s. Also known as ‘new muralism’ (nuevo muralismo), this moment of print-based experimentation implied, among other things, an assimilation of the means of distribution of cultural products and information systems, conditions close to what Rivera or Siqueiros hinted at from the ‘Graphic Assembly’. Among these practices of revival, we can name: the reuse of Adolfo Mexiac’s engraving Libertad de expresión (1954) during the student revolt of 1968, the graphic and media prints of Chicano Grupo Asco in 1976, or the transborder illustrations by Rini Templeton produced betwixt the US, Mexico and Nicaragua from the 1970s to the 1980s. These examples allow us to leave open a debate on the re-signification of the TGP in the 1970s, taking into account its references, work formats and critical derivations. In this sense, this text proposes to rethink the possible analyses of ‘those other murals’.

Footnotes

-

Walter Benjamin, Autor como productor (trans. Bolívar Echeverría), Mexico:

Ítaca, 2004. -

See, for instance, Hanner Meyer, Memoria del Comité Administrador del Programa Federal de Construcción de Escuelas 1944-1946, Mexico: SEP, 1947.

-

Juan O’Gorman refers to the TGP’s closeness to the Partido Popular and support for socialist leader Vicente Lombardo Toledano in ‘Asamblea popular’, Raquel Tibol, Gráfica y neográfica en México, Mexico: SEP, 1987, p.89.

-

Pilar García and James Oles (ed.), Gritos desde el archivo: grabado político del Taller de Gráfica Popular. Colección Academia de Artes/Shouts from the Archive. Political Prints from the Taller de Gráfica Popular, Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Difusión Cultural UNAM: Colección Blaisten/Centro Cultural Universitario Tlatelolco, 2008.

-

An extensive list of the various participants was compiled by Raquel Tibol: ‘[The TGP] was created in 1937 by Leopoldo Méndez, Pablo O’Higgins, and Luis Arenal because there was an urgent need for various forms of struggle against fascism. They were joined by Ignacio Aguirre, Raúl Anguiano, Ángel Bracho, Jesús Escobedo, Everardo Ramírez, Antonio Pujol, Gonzalo Paz Pérez and Alfredo Zalce. They wanted their efforts to benefit the progressive democratic interests of the Mexican people. Later, José Chávez Morado, Francisco Mora, Roberto Berdecio, Fernando Castro Pacheco, Francisco Dosamante, Agustín Villagra, Isidoro Ocampo, Antonio Franco, Guillermo Monroy, Mariana Yampolsky, Elizabeth Catlett, Alberto Beltrán, Arturo García Bustos, Rini Templeton joined them. In the course of twenty years many of those mentioned had left the TGP. […] But new elements joined and among them a considerable number of women: Celia Calderón, Lorenzo Guerrero, Andrea Gómez, Elena Huerta, Xavier Íñiguez, Marcelino L. Jiménez, Sarah Jiménez, Carlos Jurado, Francisco Luna, María Luisa Martín, Fanny Rabel, Adolfo Mexiac, Adolfo Quinteros.’ R. Tibol, Gráfica y neográfica en México, op. cit., pp.111–12.

-

P. García and J. Oles, Gritos desde el archivo, op. cit., pp.41–80.

-

Diana Wechsler called these kinds of image relationships that aim to generate a high impact by recovering efficient iconographies ‘emergency images’. They inlcude the Executions by Goya, the Scream by Munch, or Christian iconography, reactivated in new possibilities. Diana Wechsler, ‘Imágenes en el campo de batalla’, Fuego cruzado. Representaciones de la guerra civil en la prensa argentina, 1936–1940, Buenos Aires: Fundación Provincial de Artes Plásticas Rafael Boti, 2005, p.39.

-

Ana Lau Jaiven, ‘La Unión Nacional de Mujeres Mexicanas. Entre el comunismo y el feminismo’, La Ventana. Revista de Estudio de Género, vol.5, no.40, July – December 2014.

-

In recent years there have been rereadings of the graphic arts that give it a fundamental role in regional artistic developments. Specialists such as Silvia Dolinko, Roberto Amigo and Francisco Reyes Palma have demonstrated the relevance of the graphic medium to understand the forms of propaganda of

political, peasant and workers’ movements. As for the new studies of graphics

and printmaking, the works of Harper Montgomery, Natalia Majluf and John Ittman stand out. See Harper Montgomery, The Mobility of Modernism: Art

and Criticism in 1920s Latin America, Austin: University of Texas Press, 2017;

Natalia Majluf, ‘Indigenism as Avant-Garde. The Graphics Arts’, Beverly Adams

and Natalia Majluf (ed.), The Avant-Garde Networks of Amauta: Argentina, Mexico, and Peru in the 1920s, Madrid, Lima and Austin: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Asociación Museo de Arte de Lima – MALI and

Blanton Museum of Art, 2019, pp.138–49; John W. Ittman, Mexico and Modern

Printmaking: A Revolution in the Graphic Arts, 1920 to 1950, Philadelphia, San

Antonio and New Haven: Philadelphia Museum of Art, McNay Art Museum

and Yale University Press, 2006. -

To understand complementary definitions for the portable murals in the 1930s, see Anna Indych López, Mexican Muralism Without Walls: the critical reception of portable work by Orozco, Rivera, and Siqueiros in the United States, 1927-1940, Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2009.

-

E. Carmen Ramos, Painting the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now, Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2020.

-

Francisco Reyes Palma, ‘Utopías del desencanto/Utopias of Disenchantment’, in P. García and J. Oles, Gritos desde el archivo, op. cit.

-

Ibid.

-

Emily Schlemowitz, ‘David Alfaro Siqueiros’s Pivotal Endeavor: Realizing the

“New York Manifesto” in the Siqueiros Experimental Workshop of 1936’, master thesis, City University of New York, 2016. -

In the 1930s, Siqueiros assumed his role as a political artist under the banner of the Popular Front. The artist collaborated in forums such as the 1936 Congress of American Artists, where he participated with authors such as Meyer Schapiro, Lewis Mumford and José Clemente Orozco. This meant, in turn, the creation of an artistic production structure with new technical conditions for the work. Two of these examples carried out by the painter were: the experience at the Siqueiros Experimental Workshop in New York and the mural Portrait of the Bourgeoisie for the Sindicato Mexicano de Electricistas (Mexican Electricians Union, SME). These cases show the radicalisation of production and collective organisation in the artist’s painting. Natalia de la Rosa, ‘Épica escenográfica. David Alfaro Siqueiros: acción dramática, trucaje cinemático y la construcción del realismo alegórico en la guerra’, doctoral thesis, National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), 2016.

-

Karl Marx, La tecnología del capital (trans. Bolívar Echeverría), Mexico: Ítaca, 2008.

-

Karl Marx, La tecnología del capital (trans. Bolívar Echeverría), Mexico: Ítaca, 2008.

-

F. Reyes Palma, ‘Utopías del desencanto/Utopias of Disenchantment’, op. cit., pp.33–34.

-

D. Caplow, Leopoldo Méndez: Revolutionary Art and the Mexican Print,

op. cit., pp.11–122. -

‘Estatutos del Taller de Gráfica Popular’, in P. García and J. Oles, Gritos desde

el archivo, op. cit., pp.22–23. -

R. Tibol, Gráficas y neográficas en Mexico, op. cit., p.69.

-

Patrick Iber, Neither Peace nor Freedom: The Cultural Cold War in Latin America, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015.

-

R. Tibol, Gráficas y neográficas en Mexico, op. cit., p.69.

-

Ibid., p.78.

-

Ibid.

-

Ibid.

-

Viviana Gelado, Poéticas de la transgresión: vanguardia y cultura popular en los años veinte en América Latina, Buenos Aires: Corregidor, 2007, p.80.

-

Francisco Quevedo, ‘El alma de nuestra raza y el folklore artístico’, Revista de Revistas. El Semanario Nacional, vol.7, no.323, July 1916.

-

Beatriz Urías, Historias secretas del racismo en México (1920–1950), Mexico: Tusquets, 2005.

-

Yásnaya Elena Aguilar Gil, ¿Nunca más un México sin nosotros?, San Cristóbal

de las Casas, Oaxaca, CIDECI-Unitierra Chiapas, 2018. -

Renato González Mello, ‘Razas, clases y castas. La invención pictórica del campesino’, Memoria de Simposio. Nuevas miradas a los murales de la Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico: SEP, 2018, pp.9–26.

-

V. Gelado, Poéticas de la transgresión, op. cit., p.80.

-

Jean Charlot, ‘A precursor of the Mexican Art Movement: The engraver Posada’,

Revista de Revistas: Semanario Nacional, 30 August 1925. -

Diego Rivera, ¿Quiénes levantarán el monumento a Posada/Who will raise the

monument to Posada?, Mexico: Mexican Folkways, 1930. -

By popular prints we refer to those prints, sheets, leaflets, booklets and flyers with news and various information that, in the case of Mexico, have their origin in the prints disseminated by the Spaniards after the Conquest and became reading material in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Mariana Masera, Briseida Castro, Anastasia Krutitskaya and Grecia Monroy, ‘Los impresos populares de principios de siglo XX (1900-1917): entre la oralidad y la escritura’, in Yanna Hadatty Mora, Norma Lojero Vega and Rafael Mondragón Velázquez (ed.), Historia de las literaturas en México. Siglos XX y XXI, Mexico City: UNAM, Coordinación de Humanidades, Instituto de Investigaciones Filológicas, Instituto de Investigaciones Bibliográficas, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, 2019, p 43.

-

Ibid., p.47.

-

Ibid., p.51.

-

Ibid., p.51.