Anyone who visited the parallel exhibitions at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam and the Kunsthalle Bern ran slap – and literally, with works piled at his feet – into emergency situations. A museographic emergency: the disconcerting impact of organic materials, the intentions of the exhibitors and instruments adopted turned the museum into a transit store, especially and significantly in Bern. And an intellectual emergency: the longer you walked around the more you found yourself an object among objects, an explorer among explorations with, in several cases, works that had to be identified, attributed or even discovered. I am, of course, speaking for the non-experts, but include the art critics in this category. The art in question tends to annihilate the distinction between the initiated and the non-initiated, replacing it with the even more imposing difference between the informed and those who do not know how or where to look for information. Admitting that he is able to keep abreast of ideas, the critic is losing control of events and, luckily, of his pet systems of classification. The Amsterdam and Bern exhibitions have, in any case, officially launched an artistic revolution that is already very much in the news. Although the artists invited to one or other of the two exhibitions were about eighty, they are now multiplying, in hundreds everywhere. Conformism? I must admit that I am not at all clear whether one should, today, continue to insist on the separation or classification of inventors and copiers, leaders and followers. More than anything else, it is a question of marketing and history. These notes are intended to provide some information on the art that is being produced at present in that sector of visual and non-visual culture which might more usefully be entrusted – rather than to the art critics – to the critical instruments of cultural anthropology.

From Ithaca to Vesuvius

As happened with concepts and their tangible expression, operative spaces, means of communication and places themselves are, as the artistic revolution progresses, gradually being invaded, laboriously, by a process of the gold- rush type. In Amsterdam the accent was on cryptostructures: and, effectively, many artists are working in conditions of geographical isolation, with mental appointments and secret actions. This is the ‘conceptual’ trend of an art that is using a wide variety of resources to shift the aesthetic potential of the most concrete but also the least known of all worlds. Even the least conceptual of artists are vying with each other to bring about a crisis in the studio, the gallery and the museum. ‘Live in Your Head’, the slogan of the Bern exhibition, goes as far as including the stimuli imposed by their sometimes weighty material inventions on memory and imagination. This does not alter the fact that we are looking at a process of aesthetic ‘distribution’, heterodox though it may be. Here are some facts:

– While the large-scale itinerant exhibition of ‘New Media: New Methods’, organised for the Museum of Modern Art in New York by Kynaston McShine is still touring the US museums, the US is making contact and becoming semi-officially involved with this sort of art, as, for example, at the exhibition at Cornell University, Ithaca, New York. 01 The university followed the Dwan Gallery [New York] in exhibiting Earth works by [Jan] Dibbets, [Hans] Haacke, [Richard] Long, [Robert] Morris, [Dennis] Oppenheim, [Robert] Smithson and [Günther] Uecker, achieved on the spot either directly by the artists themselves or from plans, thus has been rendered unto Ithaca that which is of Ithaca (earth and collaboration) and not only that which is of New York.

– Having visited the museum in Amsterdam, I went to see Jan Dibbets at his home in Hasebroekstraat, and it was he who informed me that the reliefs, with photographs, exhibited at the Kunsthalle Bern, and related to the ditches he had dug at the four corners of that museum, are not works of art, but work in progress, the materials from which Seth Siegelaub is to publish in a book on him which will be his real work of art. Take a look at one of his recent conceptual works: a postcard showing number 20 Hasebroekstraat, with the window from which, at a set time on a set day, the artist will try to hitch-hike.

–The media are the new operative areas conquered by these immaterial expressions; while Pop and technological art have abused the images provided by the means of communication and use their informative characteristics to transmit new ones, Conceptual art is using books, films, etc. as mere vehicles. Seth Siegelaub, who is publishing books on artists in New York without the slightest emphasis on typographical invention (his invention, if at all, is in the financial adventure), has published a Xerox book: the xerograph copies being the only way of remaining faithful to the work of artists who have generally simply adapted their ideas to the dynamics of reading.

–The Gerry Schum Gallery in Berlin, not content with producing a Land art exhibition in the form of documents and findings assembled in the gallery, has now spent eight months shooting a film called Land art for German TV on the actual locations of the various events (featuring [Marinus] Boezem, Dibbets, [Barry] Flanagan, [Michael] Heizer, Long, [Walter] De Maria, Oppenheim and Smithson). It was broadcast on the first programme on the evening of 15 April of this year.

– On the same day, an even more resounding event took place in Naples, where a group of local artists inspired by Gianni Pisani and calling themselves the Inexistent Gallery created an ‘eruption’ inside the crater of Vesuvius by setting fire to motor-tyres, kerosene and explosives: 02 ‘reverberations, tongues of flame and columns of smoke from Vesuvius caused panic among the inhabitants of Portici and Ercolano’, the newspapers reported with angry comments. Strangely enough, the comment of a later radio news programme was understanding in tone.

The commitment to face up to reality, as declared by [Robert] Rauschenberg and [Allan] Kaprow, New Dada and Nouveau Réalisme, seems by now to have relapsed into a more cooperative attitude of osmosis with it. This has led to the emergence of a global reality of concepts and actions in which no further distinction is made between the old ideas of structure (urban reality, technology and politico-economic conditioning) and superstructure (art objects, aesthetic projections, etc.). City and desert, Ithaca and Vesuvius, art over the telephone and art through films or books: the differences are considered to be purely instrumental – as with Pop art, first, and then Funk art – despite the different contents of their procedures through fetish. While the one was ornamental and the other dissenting, one dealing in white magic and the other in black, the new artistic trend also fully accepts the ‘sign’ nature of reality. But it goes to find these signs wherever they are to be found and transmits them through every possible vehicle. One convention does remain however, perhaps the only one that can be shared by such different and fundamental experiences: that whatever the image, the place and the means, you are dealing always and declaredly with a work of art.

Journey to the end of non-art

‘Rauschenberg’s dreamy concoctions no longer attack us,’ wrote [Anton] Ehrenzweig, an expert on psychoanalysis and art, in 1965–66, ‘to my mind they may be the harbingers of an altogether friendlier art that I feel is in the air. Something more positive may be needed, aiming at constructive results rather than demolishing existing formulae and clichés.’

Ehrenzweig drew this conclusion from his analysis of the creative process. And the present-day researches, which seem to confirm this prediction, have as their dominant theme this very creative process – understood as an image of itself and experienced as an end in itself to be extended to the initiative of the majority. Historically, we are at the last gasp of an art that is involved, to a greater or lesser degree mentally, in a self-destructive spiral that turned its own results into symbols for contemplation. It is as if fifty years of history were reversing the funnel of its own optics: the eye of today no longer creates against the vast perspective of various pasts: the mass of culture and material existence that was destroyed to obtain a distillation of pure novelty, a filter that was suspect, etc., is no longer seen as the opaque barrier of the exterior world; it is seen, rather, as a background, or even a goal to be attained, for aesthetic operations distributed in the individual, through individuality, and along the whole perimeter of the external and real world.

‘Op Losse Schroeven (Situations and Cryptostructures)’, an exhibition held at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 15 March–27 April 1969

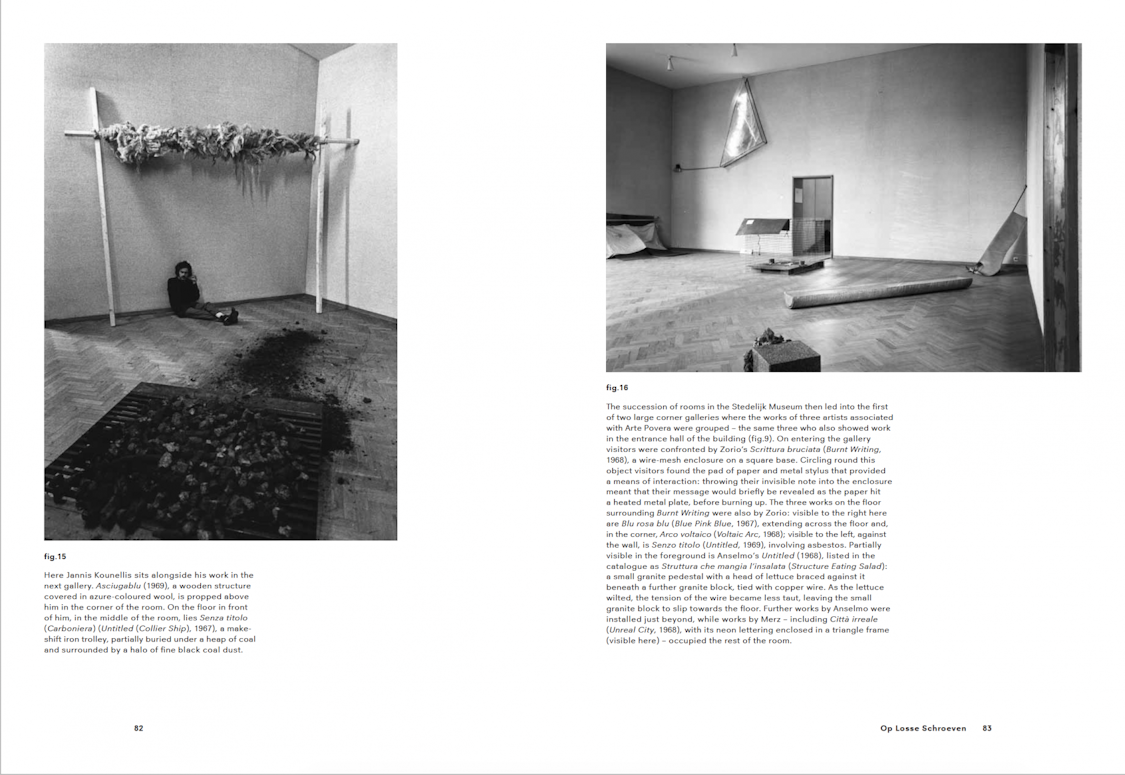

This exhibition in Amsterdam is well arranged, with separate rooms for all – or almost all – the artists, and thus does something towards coordinating the chaotic compression that made the scene at the Kunsthalle Bern so attractive and contradictory. But the order is contrived and presents together compound and unduly emphatic works, such as Richard Long’s stone sculptures – a more or less inert borrowing from nature – or Ger van Elk’s sheet, set up rather like a sail. Most of the artists on view in Bern are to be seen here too. And, of course, the same problem crops up: how to reconcile a museum or gallery with the time element that is involved in the majority of these works? On the one hand a static element, space; on the other, actions worked out in time. Robert Morris, for example, like Smithson, Long, Heizer, Oppenheim and the German [Reiner] Ruthenbeck, exhibits an Earth work. His project, which was executed by the museum, called for the collection of a number of combustible materials to be freely arranged on the ground throughout the exhibition and set on fire on closing day. But what we saw was inert piles of peat, magnesium, coal, etc., not unlike the inert heaps of earth by Ruthenbeck or Smithson (the first put iron embroideries on top, the second stuck a mirror into his). Art as a process in time, action that involves, a work that becomes transformed into destruction or regeneration, dies as soon as it is brought into a museum unless it arrives there already anaesthetised. (Aesthetics is anaesthetics, says Mario Merz). This is a difficulty that the enthusiastic organiser of the exhibition, Wim Beeren, cannot conceal even in the title: ‘Op Losse Schroeven’, or ‘Square Pegs in Round Holes’, which is as much as to say the irrationality of rationalised communication.

And so it is the catalogue that completes the work, providing clarificatory information. The Stedelijk adds, to the brilliant piece of classifying prepared for Bern by [Harald] Szeemann, a catalogue that is half a book, half a collection of projects. I do not know whether it is accurate to use the word ‘magic’ for the intentions of the new art in general, especially that coming from America, but there is no doubt about its intention to control the energy of the behaviour and attitude of matter, and hence also the control of information, of the specific nature of the means by which such energy is channelled. In addition to the space of its rooms, a museum is now apparently expected to provide not only a direct aesthetic experience, but a supporting programme of books, films and TV – with or without industrial sponsors. And this is the intention behind the next Bologna Biennale. And it is also being done by the Los Angeles [County] Museum [of Art] for the forthcoming ‘art and technology’ exhibition, which will bring together technological artists and ‘outsiders’ like [Claes] Oldenburg. 03

Moreover, the works by Walter De Maria – who provides a mattress on which you can lie down and relax as you listen to the sounds through headphones – and Bruce Nauman, are technological elaborates. In the semi- darkness of his room, alongside the elongated words spelt out in strip- lighting (‘my name as if it were written on the surface of the moon’), Nauman continuously screens a number of films: images of himself playing the violin or with two balls inside a court marked out in his studio, walking or dancing round the studio to the appropriate sound effects. This is a fascinating spectacle and helps to sugar the pill of a brute reality: compared with their European counterparts, the Americans not only have better means at their disposal, but also benefit from the ‘psycho-cultural distance’ ([Noam] Chomsky) which separates the US – where technological intelligentsia is coming into power – from us their ‘poor’ neighbours. 04

In addition to the Italians who showed at Bern, invitations were sent to Marisa Merz, Paolo Icaro and Pier Paolo Calzolari: and this is a genuinely cryptic intervention involving, of necessity, the sole authority of intuitive complicity in thoroughly individual rites. There is no longer the gesture that assaults in order to define ([Richard] Serra), the reconstruction of a natural existence through active materials (Oppenheim) or a confident and humanising activity in a world that, all the same, remains beyond the human yardstick ([Joseph] Beuys). At the risk of solipsist involution, these artists aim at lifelike authenticity and communication in terms of faith, and this is revealed by their ‘sectarian’ and apparently secret expressions. Icaro tells a story in stained glass using infantile designs; Calzolari uses lead, sprayed foam and writing in ice to make a map of delicate itineraries and barely articulated thoughts. Similarly Marisa Merz projects the rhythm of her own life into her manufactures. ‘Not actions but biological extensions of herself,’ writes Emilio Prini, ‘identical (to herself) alien (to the world) exchangeable (with a friend).’

One-man show of Michelangelo Pistoletto at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, 22 March –24 May 1969

As inevitably happens at group exhibitions, any approach to the individuals at Bern or Amsterdam involved paddling in the unnecessarily gooey dough of similarities and differences. An overall vision is not yet a global vision, necessarily circular. Nowadays, paradoxically enough, group shows reject not only the individual but the intense thirst for individuation that these artists are trying to convey to the visitor through what they do and are – since their shows are works in themselves, events in themselves. And this is the constitutional defect of the whole story of contemporary art: groups and movements prey like phagocytes on the process of individuation in both creator and exploiter, and abstraction obfuscates any prior observation of the concrete and isolated. Just an hour’s journey from Amsterdam, Pistoletto’s one-man show overturned the approach that had been followed up to then by completing it: the reproof had hitherto been that, when it comes to this new ‘situational’ art, the works may be allowed to resemble each other, but not the artists. While, in Amsterdam, the individuals were perched on a sort of dyke overlooking the new lands conquered by art, Rotterdam restored the individual adventure and the imprint of personality. There, a general idea was expressed in different works, pluridirectionally; here, a global work was arranged on different lines of thought. And, in any case, the brief but illusory itinerary for ’s-Hertogenbosch, Otterlo and Delft was surely a witness of other whole periods, other group situations, distilled through the unmistakable individuality/universality of a [Hieronymus] Bosch, a [Vincent] van Gogh or a [Johannes] Vermeer. As we move into the 1970s, exhibitions like those at Bern and Amsterdam sanction the demise of the avant-garde through the disintegration of the movements. Polyphonic works take over from orchestral movements.

Pistoletto, too, was trying to exhibit the unexhibitable: the series of ‘minor’ works he elaborated and exhibited in his studio in the summer of 1966 were later destroyed or transformed. In his exemplary one-man show at the Boijmans Van Beuningen (a little-known museum, hitherto famous only for ‘The Prodigal Son’ and three or four other masterpieces by Hieronymus Bosch), some of these works reappear in the super-enlargements to be seen in the entrance section, reproducing his own studio. Far from being merely the private recovery of lost images, he here restores to us a key moment in what was later to be called the Turin School. There was a great deal of activity around the Sperone Gallery in 1966: in February, [Pino] Pascali was finally given the chance, with Pistoletto’s help, to exhibit his ‘canons’ which had been refused in Rome; in the summer there was the group exhibition of ‘arte abitabile’ (‘inhabitable art’); in the autumn the work of [Giovanni] Anselmo, Mario Merz and [Gilberto] Zorio attained stability, and then there was [Piero] Gilardi’s critical work. This marked the appearance of the new techniques of the creative process (and not merely constructional or artistic techniques) about which Pistoletto was to theorise in his pamphlet ‘Le ultime parole famose’ [‘Famous Last Words’] in 1967: materialisation of single perceptions, ‘less’ work as liberation and not a construction representing the artist, the release from formal problems, and conclusively from the evolution of languages… The ‘portico’ in cement, the wonderful ‘burnt rose’, the fibreglass wells ‘with cardboard’ or ‘with mosquito net’, the ‘twisted panels’ and on and on down to his most recent works, including ‘the earth and the moon’ and ‘orchestra of rags’, which are very fine because of the self-sufficient energy they hold back – these flashes of interrupted fantasy now appear to us as naturally coordinated in a range that certainly is, as is the case with many young artists, a theatre of space and time, but in Pistoletto’s case it is enclosed within an individual circle of space and time (to avoid the word ‘interior’, as the word is ambiguous and ambiguities are not yet well enough appreciated) in a theatre, to sum it all up, of creativity. The fulcrum of the exhibition-event, which concludes retrospectively with a selection of mirror paintings, is the ‘labyrinth’ of rolls of white corrugated cardboard. In its windings there are three trombones, like long Tibetan horns. Pistoletto sees many of his present works as scenic objects for the spectacle of the ‘Zoo’. The theatrical activity of this group, which moved on from Holland to a German debut, is also a natural corollary to Pistoletto’s visual and spatial researches. His labyrinth is not an environment, nor are his rags Anti-Form: they are accumulations of primary energy which recall, rather, the word ‘self-sufficient’ or ‘self-entangled’, as coined by [Velimir] Chlébnikov. In breaking down discourse and organised languages, the new generation has consumed all the metaphysical humours with which New Dada and the Nouveaux Réalistes were still impregnated. The object of their experiments is shifting on several lines of thought towards the interior of the creative process, while still increasing contacts with and knowledge of the external world. If the mirror provided Pistoletto with a non-aggressive measurement of the world, these objects and scenic spaces provide him with a personal itinerary of individuation: the labyrinth as a yardstick of itself and relations with external reality.

‘When Attitudes Become Form (Works – Concepts – Processes – Situations – Information’, an exhibition held at the Kunsthalle Bern, 22 March–27 April [sic] 1969 Harald Szeemann has achieved what will be looked on as the key exhibition of 1969 as far as international ventures are concerned, through the unaided strength of the realistic approach. ‘When Attitudes Become Form’ is presented with all its contradictions. It is a census of the new artistic experiments that have succeeded Pop and Minimal art, on both sides of the Atlantic, and, at the same time, official recognition of Anti-Form, Arte Povera and Earth works. Bern has thus stepped ahead of Paris, where the climate is one of ostracism towards innovations that upset, to a greater or lesser extent, the ‘guilty consciences’ of those critics and intellectuals in general who are precariously poised between aesthetics and politics, and has offered a duty-free clearing house to New York, where they have been temporising, though it is by no means clear whether to avoid the explicit disagreement of the artists or to be in a better position to make their own selections and impose conditions. But Bern is also a spiritual desert which has been surrounded with vacancy, if this can be accepted as a definition of the mixture of indifference and hostility manifested by the ‘low horizon’ of the Swiss capital, the true aesthetic experience presupposed by these researches: the animation and provocation of the feeling for life and nature, the extension of the ego and transformation of the libido, both on the part of the artist-actors and the participating visitors. The deserved success of this exhibition has signalled the failure of these experiments, or, rather, has demonstrated in vitro their congenital tendency towards failure in any circumstances. The proof of this is in the fact that, from Krefeld to Stockholm, this same exhibition is to tour another eleven cities with its load of lead and earth, and with the odd bits of rubble ready to be restored. Like a rather botched film. When the attitudes of a museum become formal, we find a shop window instead of a research centre, a warehouse instead of a school. The Kunsthalle Bern, packaged by Christo and rendered by Szeemann an outpost of art promotion that extends beyond the European, has now literally been handed over to the requirements of the artists. It has also revealed that despite such openings there is no solution on the museographic plane or the reality-hunger of the art of today.

Richard Artschwager, with his disturbing blps, fibrous signals scattered in the least-expected corners as in a spatial puzzle; Joseph Beuys, with his obsessive ‘Ja, ja, ja… nee, nee, nee’ repeated on an endless tape beside a pile of felt as obtuse as the evil-smelling mixture of fats that obstructed the corner of the room; Ger van Elk, with his elusive intervention in substituting a photographic reproduction for one of the floor tiles; and Robert Barry, with his invisible radiation from ‘uranyl nitrate (UO2 (NO3)2)’, created on the museum building, have all contributed towards making the exhibition an experiment in exploration (and frustration), together with the dozen artists (Jared Bark, Ted Glass, Hans Haacke, Jo A. Kaplan, Richard Long, Bernd Lohaus, Roelof Louw, Bruce McLean, David Medalla, Dennis Oppenheim, Paul Pechter, William G. Wegman, etc.) who were represented only by information, often photographic, on ideas and works that were not realisable. The contribution of the Americans was impressive, with that of Richard Serra in a class of its own, introducing his molten splashed lead against the wall, beside tubes in the same material and his large fresco in India rubber and neon light. Keith Sonnier, Frank Viner, Eva Hesse, Richard Tuttle, Robert Ryman and Bruce Nauman articulate with less credibility, perhaps, but more sensitivity than the aggressive Serra, the discourse on non-rigidity, or Anti-Form; as the reverse of the medal of the attitude of Minimal art, Anti-Form constitutes a modest discarding of syntax in a language that finds in Claes Oldenburg its true sense of individual projection, and in Christo the real power of art as a process in time.

The French artists, Alain Jacquet, with his baring of the electrical nervous system by means of random wires, and Sarkis, who exposed chemical processes by the immersion of aluminium, film and neon in water, are already approaching the Italian horizon. Here, Mario Merz, Giovanni Anselmo and Gilberto Zorio converge in defining the original tone of the experiments that were worked out in Turin. The attitude is existential, and the form a mere result of constructional procedures. The igloo of broken glass, the mastic relief and the wax ‘sit-in’, all testify to the lofty and mature sensitivity of Merz. Anselmo discharges dangerous electric charges into the concrete, or fixes strips of damp cotton wool onto the windows. The torch of bamboo and electricity, the flares and reeds of Zorio, confirm the general tendency to create ‘living’ rather than lived objects. This tension transferred from man to object is particular to experiments that are at present being worked out in Italy. A tension that makes them appear more precarious, certainly more discursive and even narrative than the more intellectual and objective American equivalents. The Italians, however, have a stronger desire to render the manual and material energy required by the creative act more permanent, and to permeate the spectator in it. The public had reduced to a shapeless mass the human figure in cement balls with which Alighiero Boetti creates the image of ‘Alighiero Sunbathing in Turin’ on the ground. The only artist to work on signs, Boetti covers a blackboard with chalk to turn it into a ‘moon’, or traces in pencil the geometry of a sheet of squared paper with an obsession that is almost paranoid, recording the sound and rhythm of the operation.

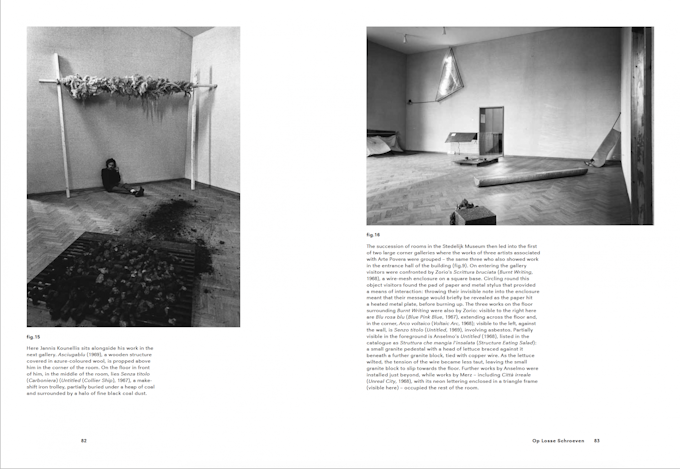

Equally evident is the sense of the private, of daily existence, [in the work of] Janis Kounellis. This Roman artist got over the fact that his works failed to arrive by buying up foodstuffs (beans, flour, peas, etc.) and placing them in sacks, exhibiting them as if the museum was a wholesale market. Kounellis’s extreme inventive capacity here attains another significant result; while Morris and Smithson accumulate industrial archaeology, by choosing rocks and combustible materials with the detachment of naturalists, Kounellis acts as a dispenser, using wool, coal and dried vegetables to make a rustic archaeological warehouse; while Beuys and Serra accumulate pears and lead as their chosen materials, he reinvents his world with what he finds locally. The Italian participation, then, provided the best examples of authenticity of attitude. And this was despite the fact that Pascali and Pistoletto, although invited, were not represented for various reasons, and the same applied to Calzolari, Icaro and Prini (who were, however, fortunately, to be seen in Amsterdam). Nor is it clear why Piero Manzoni should have been forgotten. Most opportunely, a connection was made with Yves Klein, whose ‘oeuvre immaterielle’ is referred to here through a story by Edward Kienholz, but no reference was made to the creator of ‘lines’, the discoverer, at least here in Italy, of a series of aesthetic experiences for which ‘all that is necessary is to be’. But it is also true that the same omission is still being made here at home, where we are incredibly disposed – as in the case of the book dedicated by [Germano] Celant to Arte Povera – to invent situations which end up by eliminating, together with Manzoni, even the key works of Pascali.

Tommaso Trini

–

Editors’ Note: This text was originally published in Domus, vol.478, no.9, September 1969, pp.45–53. It is republished courtesy of Editoriale Domus.

Footnotes

-

Editors’ Note: ‘Earth Art’, curated by Willoughby Sharp for the Andrew Dickson White Museum of Art at Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, 11 February–16 March 1969.

-

EN: The actually non-existent Galleria Inesistente was founded by Giannetto Bravi, Gianni Pisani and a group of artists from Naples in 1969.

-

EN: The Art and Technology programme, organised by Maurice Tuchman for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art between 1967 and 1971, included contributions by, among many others, Michael Asher, Larry Bell, Hans Haacke, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Smithson and Karlheinz Stockhausen.

-

EN: For Chomsky’s discussion of the ‘psycho-cultural gap’, see Noam Chomsky, ‘The Menace of Liberal Scholarship’, The New York Review of Books, 2 January 1969, also available at http://www.chomsky.info/articles/19690102.htm (last accessed on 24 June 2010).