Why, when this span of life might be fleeted away

as laurel, a little darker than all

the surrounding green, with tiny waves on the border

of every leaf (like the smile of a wind): – oh, why

have to be human, and shunning Destiny,

long for Destiny? […]

[B]ecause being here is much, and because all this

that’s here, so fleeting, seems to require us and strangel

y concerns us. Us the most fleeting of all. Just once,

everything, only for once. Once and no more. And we, too,

once. And never again. But this

having been once on earth – can it ever be cancelled?

Rainer Maria Rilke, ‘Ninth Elegy’, Duino Elegies (1923)

I don’t remember how Silke Otto-Knapp, who died a few weeks ago at home in Los Angeles, got the job as Managing Editor of Afterall Journal in 1999, though there must have been a formal interview procedure. I do, however, have a vivid image of her arriving at the office for the first time in a beautiful white summer dress with bright yellow shoes, effortlessly glamorous, filling the room with preternatural charm and curiosity and instantly the cynosure of all eyes. If an interview did indeed succeed that entrance, it would obviously have been superfluous.

It seemed that almost everyone knew Silke. She held attention, her commitment to friends was legion and she gathered these in numbers that few others could ever hope to match. And if they were also a little scared of her at times, they never failed to find her interesting and provocative. Silke was very kind. If you were filled, say, with doubt and self-loathing, she would sense this and say things that emphasised decency and success. It was never fake, or opportunistic, and it was easy to feel more confident, and certainly less miserable after listening to her addressing your concern and complaint. Silke knew that people are only nice when other people help to make them nice.

At Afterall, Silke was an exaggerated presence and she needed to be. Until she arrived everything was a mess, and nothing useful was yet in place. By the time she left, most of the mess was gone and lots of structure had been imposed. Silke got things done, properly, efficiently, and as the journal’s stature grew, so did hers. Silke’s editing was respectful. She could not abide magniloquence – florid prose would emerge from her edit with improved sensibility. And as she loved poetry and literature, she was careful not to rob a critical text of its rhythm and rhyme. Silke encouraged us to recognise our intellectual, formal, and administrative obligations. There were things for disagreement, of course, but these were anecdotal and temporary, against the important evolution of Afterall into something increasingly international and ambitious.

Silke knew that if you weren’t ambitious you would never do something you hadn’t done before. Like spending five cold, damp morning hours at sea, waiting patiently for the excitement of the first tug of a line, and then at the point of near exhaustion, Silke, wearing her distinctive blue rain coat, hat pulled generously over her head, oversized glasses covered in sea spray, the boat listing precariously in the ocean swell, holding up her giant codfish, her face beaming with accomplishment. Or meeting so many different kinds of people, people she might have heard about, or who struck her as a fascination to pursue on the basis of a few brief words at an opening, on a boat, or simply because she had read about them somewhere. She needed to make good friends, and she did, everywhere.

Soon after Silke joined Afterall, we began an editorial partnership with the California Institute of the Arts and our friend and artist Thomas Lawson became an editor. This new collaboration took Silke to Los Angeles for regular editorial meetings and the journal began to feature a number of artists and writers living in and around the city. Here began the many friendships that grew up around Silke as she, unknowingly at first, prepared for her inevitable and, as it turns out, final move to Los Angeles. Though Silke was peripatetic, moving from city to city, country to country, strangely, to those of us left behind, it often seemed that she had never really gone, so committed was she to the friendships she had made and the scenes she was once a driving force of.

Silke could dramatically change the mood with a look. At one of our California dinner meetings, someone at a table nearby began to lick the inside of an empty yogurt container, getting his tongue particularly stuck into a difficult to get at corner, oblivious of the spectacle he was making; until, that is, he noticed Silke staring at him with such incredulous contempt that he seemed to shrink three full sizes, as if trying to disappear inside his own clothes. On another occasion when I provocatively proposed a particular artist that we might feature in the journal, she gave me a long pained but ultimately forgiving look, allowing me time to make a correction, which of course, one way or another, I probably did. Now that I think of it, this would happen many times with similar results by and large. Silke’s ‘looks’ were legion, and those of them shaped by her approval were as satisfying as others could be terrifying. But even when Silke was annoyed and in her most revolutionary mode, you knew there was always love there. As Diane di Prima once wrote in ‘April Fool Birthday Poem for Grandpa’, revolution is simply love spelled backwards.01

Tom Lawson and I used to tease Silke that in editorial meetings we could argue and discuss as much as we wanted, but in the end she would decide. And of course she would deny this with a delightful little shrug that was equal parts faux indignant, coy and excited. She was happy that Tom and I were at least partly right, and also that we recognised this. But Silke’s charge was not trivial, and it usually worked well. I confess to feeling a bit jealous that she could have her way, quite so often, without causing offence. A perfect skill. Equally, if you were passionate about something you loved, Silke would get excited with you.02 I remember one afternoon we decided to skip work early and walk down the road to see the Jean Baptiste Siméon Chardin exhibition at the National Gallery. I had recently become completely obsessed with Chardin, and Silke joined me in my enthusiasm.

All history, as Jackson Lears writes, is the history of longing and it’s inside this longing where we live. Silke longed for so many things: family, painting, her career, her garden, and always her friends, the old and the new, and the ones she hadn’t met yet, but was sure she would. Silke was also fascinated, as Roland Barthes would say, by imperfect things, curious to discover what made them so fascinating.03

She finally left Afterall in 2005, letting go of the journal that bore her signature in so many ways, and deciding to take a risk and work full time in her studio, something she had certainly never done before. We were sad when she left Afterall, but happy with her for her decision to concentrate on her painting.

It took me a relatively long time to start writing these memories. I knew I wanted to write something, but mere hours after Silke’s death there came the rapid-response obituaries, the flood of Instagram posts, each post generous and kind, of course, but also a little nervous – about the responsibility of being first, and whether to have waited. A very contemporary dilemma. All of this made me pause. Silke disliked Instagram. As far as I know, she had no use for social media whatsoever, though she did have time to ponder it, try to understand it, and ultimately have an opinion on it, as she did about so many things. Silke’s opinions were always fascinating, provocative, sometimes obstinate, passionately held, and, from time to time, reassuring. Like the very opinion she had of Instagram. I remember a long discussion with her just as the brutal concept of the ‘Instagram-Ready’ work of art was beginning its ugly spread, no doubt mise en abyme on Instagram. I myself am not on any social media, so listening to Silke’s very persuasive takedown was a balm for FOMO anxiety. Art takes time was her essential argument. So blindingly obvious but very good to be reminded. For Silke, Instagram was a stupid invention like the electric carving knife, unable not to destroy the very thing on its mind. This short critical dissertation was followed by a triumphant swing of her head, up and to the left, a disapproving grimace, held for a second or two, and then the famous Silke laugh. Time to move on.

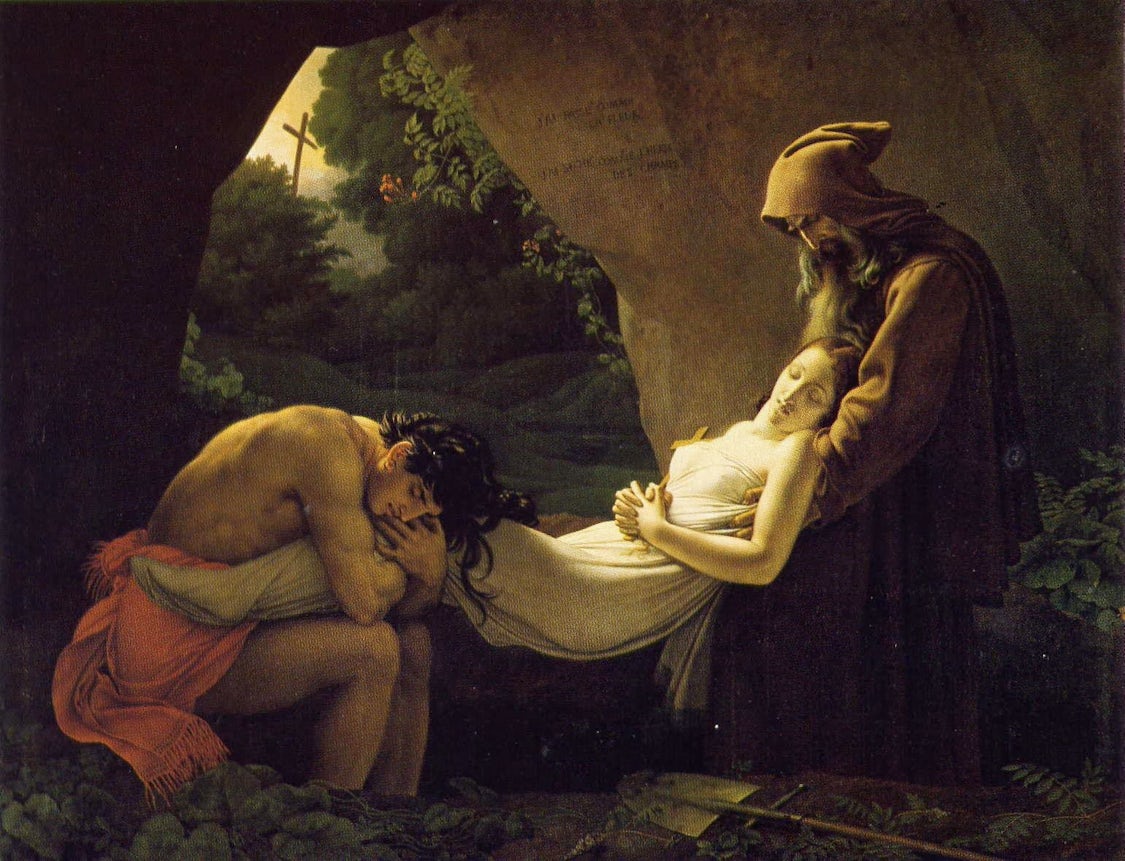

Death takes its time. In the immediate days after the death of a love or a friend, you can find yourself deep in doubt: unable to reconcile the fact of death with the persistence of memories that seem brighter, sharper, and certainly more provocative. This, for the want of a better word, interregnum fades, as indeed it must do, but it does mean that for many of us and for the time being at least, Silke is still here in different ways, and writing this and the myriad mentions, notices, posts, and articles about Silke and her work, are ways of depicting this condition, trying to keep Silke alive long enough to make the awfulness of her death a little more bearable.

Silke could be very different people, different characters, each full of charm and also challenge and she lived these lives simultaneously, while trying, to keep them discrete and independent for each group of her friends. It could be funny watching this juggling act, as Silke struggled to choose what to share and what to save for one of her other lives. To be around her was almost always exciting, if at times a little exhausting for her. But it was the aggregation of everything that made her unique and often electrifying. Silke devoured every bit of knowledge about the world that she could, loved art of so many different kinds and histories, enjoyed teaching new generations of artists, and took special care and attention of her friends’ works, enthusiastically offering considered advice and encouragement. Silke’s travel between the many places that once gave her home, was less restlessness (though perhaps it was this too), than a desire to live simultaneously in all her different worlds. Silke lived this multiverse, but in the knowledge, as Henry James puts it, “Really, universally, relations stop nowhere, and the exquisite problem of the artist is eternally but to draw, by a geometry of his [sic] own, the circle within which they shall happily appear to do so.’04 In truth, the only way Silke could slow everything down was in her work. Silke was, of course, a painter, an exceptionally rigorous one, and her work has justifiably received high critical praise.

Silke enjoyed many happy moments on Fogo Island where she spent summers, hiking, fishing, swimming for impossible lengths of time in the ice cold Atlantic Ocean, and having dinner with the many friends she made there. Most of all Silke loved the sea, and thinking about this now I am reminded of the closing lines from Last Summer in the City (1970), by Gianfranco Calligarich:05

“I think about the first fish that survived being abandoned by the waters, that struggled and gave birth to us. I think that everything leads to the sea. The sea that welcomes everything, all the things that have never succeeded in being born and those that have died forever. I think about the day when the sky will open and, for the first time or once again, they will regain their legitimacy.”

Footnotes

-

‘[…] talking love, talking revolution/which is love, spelled backwards’. Diane di Prima, ‘April Fool Birthday Poem for Grandpa’, in Revolutionary Letters, San Francisco: Last Gasp of San Francisco, (1971) 2005.

-

Unless she hated it!

-

‘The imperfect is the tense of fascination: it seems to be alive and yet it doesn’t move: imperfect presence, imperfect death; neither oblivion nor resurrection; simply the exhausting lure of memory.’ Roland Barthes, A Lover’s Discourse. Fragments (trans. Richard Howard), London: Penguin Books, 1990, p.217.

-

Henry James, ‘Preface’, in Roderick Hudson 1875.

-

Gianfranco Calligarich, Last Summer in the City (trans. André Aciman), New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021.