The artist, trained to be aware of the visual field, makes explicit the patterns governing his [sic] behavior. For this reason, the artist is not only a commentator on the larger values of the culture but on the microcultural events that go to make up larger values.

Edward T. Hall, The Hidden Dimension01

Rosalind Nashashibi became renowned after receiving the Beck’s Futures Prize in 2003. In the immediate post-Young British Artists moment in London, and as the Glasgow scene flourished, her film works stood out as a different kind of image-making. The end of the 1990s through the 2000s mark the first decade of her practice, during which she laid the ground for her investigation into humans and their behaviour. Looking specifically at the first half of her period of practice until now, having reached what is typically described as ‘mid-career’, it is inaccurate, and even diminishing, to describe her works from this period as being ‘formative’ as they are some of her defining, standout works alongside recent examples such as Vivian’s Garden (2017) and Part One and Part Two (2019). Her films from this period portray a range of social and behavioural phenomena – our relation to space, perception, interaction and proximity between people, as well as forms of communication. Working with 16mm Bolex camera and video, Nashashibi approaches her subjects, human and nonhuman alike, through a certain lens. These technologies capture ambient noise, voices and samples indiscriminately through which we witness an uncanny world. What kind of lens is this?

The artist is also known for her collaborative work with Lucy Skaer, itself multifaceted and with its own characteristics. But this body of work represents a different tack in Nashashibi’s oeuvre, which requires its own appraisal. Instead, this essay looks to provide an overview, as well as interpret and analyse Nashashibi’s first decade of solo practice. Enticing for many, her film works are beguiling to others, particularly for those that perceive them purely formalistically, or are frustrated by the absence of narrative structure, or else, mistakenly see them as ethnographic. It is simply not that kind of film-making. The old mantra of cinema criticism – that the important part, the movement, is between the frames – finds a social translation here, as the real emphasis in the artist’s films is in the relations between individual and group, and individual and environment, and also between individual and power. It is perhaps to this ‘in-between’ that we should be directing our attention. The in-between that shapes the inner world of individual subjectivity and our experience of the outer world. In this regard, I would argue that Nashashibi’s films could be seen as studies in human ‘proxemics’, a field pioneered by cultural anthropologist Edward T. Hall, which he defined at the very beginning of his book The Hidden Dimension:

Proxemics is the term I have coined for the interrelated observations and theories of man’s use of space as a specialized elaboration of culture.02

Looking at the structures of experience between individuals and in relation to their environment, proxemics considers how these factors shape reality and our perception of it. There are, according to Hall, ‘hidden’ phenomenological and linguistic relations that are rooted in cultural specificity, based on which, he contends, ‘[…] people from different cultures not only speak different languages but, what is possibly more important, inhabit different sensory worlds’.03 This understanding of culture seems particularly pertinent to revisit, as some of the core issues society faces today – such as its polarisation into different identity constituencies and thus different sensory worlds, divergent perceptions on the subjects of migration, freedom of expression and nationalism – have supposedly provoked the so-called ‘culture wars’. From this perspective, ‘culture’ has the potential of becoming divisive and dangerous.04

Despite some of its limitations and the criticism levelled at his work – a static conception of ‘culture’ aligned with positivist notions of national identity – Hall nevertheless offered a significant new contribution to cultural anthropology for reflecting on social, behavioural and perceptual patterns, that should rather be utilised to discuss cultural complexity, affect and transformation. His analyses also consider proxemics as a factor in conditions for the production of artistic work. The work of artists was analysed by Hall for considering the environmental and cultural specificities that lead to particular aesthetic practice within given regional contexts. For example, according to Hall, in the case of the Aivilik Inuit people, their art was a product of the perceptual possibilities afforded by life in the arctic where there is often no horizon to distinguish earth from sky.05 Yet conversely, contemporary artists themselves investigate environmental and behavioural conditions within their practice. One could hypothesise that over time, contemporary art has also developed its own aesthetic proxemics. We might, for example, think about historical movements such as ‘institutional critique’ that sought to elucidate the position of art and artists in the context of institutional power relations or Eurocentricity. We may additionally consider such ideas as writer André Malraux’s Le Musée Imaginaire (1947, translated to English as The Museum Without Walls) as another kind of perceptual proxemics, which describes an inherently modernist model to rethink the museum as an influx and juxtaposition of images leading to new associations between works of art. To some extent, these ideas have been integrated by institutions and artists, structuring both our experience of art and exhibitions and shaping the interpretation of works and their narratives. But with artists having increasingly looked at the inter-human and intercultural sphere, as well as their spatial dynamics, one can observe a shift or a different sensibility towards a clear interest in social engagement and in how affect traverses the social. In this regard, the intelligence of this art lies in its ability to observe subjects whilst transcending ideological patronage.

Nashashibi’s film works adopt a philosophical lens and establish sets of relationships through which the artist performs the observation of the habitat and behaviour of particular groups, some long-existing and some temporary, including their interactions and their forms of communication. From early stages in her career, her interest in the pre-verbal as well as the non-verbal is noticeable – marked often by the absence of oral language, and rather by gaze, gesture, intent and voice. For Nashashibi, the practice of art seems to be a pre- and nonverbal form of communication – a paralanguage structured by pictorial, spatial and gestalt consciousness. Yet these works are not about the artist’s introspection, and it is in no way necessary to read the works in this way. (Though they consistently demand from the viewer the answer to the question of how to view them.) The gaze of her films unfolds through the lens as a medium of study. Spaces are ‘captured’ within specific cultural settings along the lines of specimens or reports and yet, simultaneously, they portray intimate relationalities. The seemingly mundane situations depicted draw us towards the proxemics of particular groups and their spaces, from family households and suburban neighbourhoods to public arena spaces and sites of labour.

-

Rosalind Nashashibi, Midwest, 2002, 16mm, colour, sound, 12min, stills. Courtesy the artist and LUX, London -

Rosalind Nashashibi, Midwest, 2002, 16mm, colour, sound, 12min, stills. Courtesy the artist and LUX, London

The State of Things (2000) is an early example of when the artist started to adopt what I call her proxemic lens. We watch a Salvation Army jumble sale filmed in Glasgow in grainy black and white footage. In an unadorned environment – utilitarian and for leisurely activities – for a particular demographic, that of local working class families and individuals, people from the community ply through the mass of second-hand clothing – fungible goods traded for low costs – and elderly volunteers man the stalls. It is a municipal community space, and people, focussing on finding suitable items, keep in close and vying proximity. We note also that non-verbal communication passes through clothing; in this sense, we witness a situation in which registers of communication expand between social actors. The audio track adds another layer to the film, which initially sits at odds with the imagery. It is in fact the classic 1926 love song ‘Ana Hali Fi Hawaha Agab’ by the Egyptian songstress Umm Kulthum. This element that comes from a foreign place brings an important characteristic. It demonstrates Nashashibi’s approach of seeing reality as something that is relative, and thus ultimately mutable. By juxtaposing an external sonic dimension rather than recording sound on site, she creates an alternative sense of place and estranges its nature.

It was during an artist residency in Omaha, Nebraska, in the United States, that Nashashibi made the films Midwest and Midwest: Field (both 2002). Depicting a day from dawn until dusk in Omaha, we see in Midwest the comings and goings of people in the street, undertaking their daily routines and rituals, sometimes hanging around, waiting, or even sleeping. These are moments suspended from remedial life and labour. There is a certain subdued feeling. Part of the film is shot within the Mexican café Gaby’s where migrant families eat and converse. Midwest: Field, conversely, depicts a group of men flying radio-controlled planes in the flat, expansive fields outside the city. There is something particular about the combination – wide open space and mundane urban areas of the ‘New World’ – that create the conditions for both labour segregation and whimsical leisure. Common to both films is the chatter. We hear undefined voices as homogenous noise. They are like field recordings of humans, in which we hear ambient sounds and intonations rather than specific verbal sentences. In the inner-city café, the conversations are more animate, and in the landscape more sedate. The lens produces an almost ‘alien’ perspective, as if viewing human species for the first time. What it views cannot absorb the verbal, but it seems to be willing to understand the human in its environment.

-

Rosalind Nashashibi, Dahiet Al Bareed (District of the Post Office), 2002, 16mm, colour, sound, 7min, stills. Courtesy the artist and LUX, London -

Rosalind Nashashibi, Dahiet Al Bareed (District of the Post Office), 2002, 16mm, colour, sound, 7min, stills. Courtesy the artist and LUX, London

The same year, Nashashibi made Dahiet Al Bareed, District of the Post Office (2002) – the first of a number of films made in Palestine. What is captured here is of a particular suburb built originally for the Palestinian Post Office, which over time has become a sort of no-man’s land between Ramallah and East Jerusalem, where we see different situations occurring on a hot afternoon. A game of football is being played – a scene ubiquitous worldwide – however, we also see at a certain moment rubbish burning, as well as the daily goings-on in a barbershop – the ingenuously-named Sweet Love Saloon for Men. Once again, the sound takes the form of a field recording, this time of the neighbourhood, including of the adhan, or call to prayer. The film also shows leisure activities and grooming outside of the work environment, amongst a landscape of decay and degradation. Another work filmed in Palestine that shifts the focus on street life of Dahiet Al Bareed, District of the Post Office to the private sphere, is Hreash House (2004). Filmed inside a Nazareth home, we witness a day in the life of one Palestinian family preparing and then eating a Ramadan feast. The family is expansive and lives collectively. This hive of coexistence within a domestic setting forms an ecology little seen in places such as the West, but such a family structure and its rituals tradition are more typical in places like Palestine. Family – where notions of law and justice remain elusive – is kept close for safety, and tradition sustains its own perception as a tight community. A scene of a meal around a long dining table is particularly enrapt and ritualistic. Everyone eats dutifully in celebration. Little is spoken, and there is the sound of cutlery on crockery.

This is also true of The State of Things, as well as Blood and Fire and Humaniora (both 2003), which consider municipal and community spaces. Titled after the Salvation Army’s motto, Blood and Fire looks at a soup kitchen organised by a branch of the organisation in the coastal suburb of Portobello near Edinburgh. The kitchen is primarily for the elderly, who use it not only for sustenance, but also for the communitarian moment it provides. The coast becomes a kind of metaphor for life on the periphery. In societies where people in need can’t always rely on families, such as that found increasingly in the West, it becomes necessary for organisations like the Salvation Army to step in. Similarly, Humaniora looks at care, which in this case is provided by the state, looking at British hospitals of the Victorian and the post-War transformations in which the NHS (National Health Service) was formed. Central to Western welfare-state nations, public health provision became a cornerstone of the social contract between individual and state by establishing spaces for medical care and health services. The title, Humaniora, or the ‘roots of the human’, can be interpreted as referring to the humanities (as well as the arts), rather than the natural sciences, to which medicine is usually indexed, to talk about spaces of care.06 The spaces in both films are not necessarily ones you are meant to ‘like’ or wish to frequent, but are nevertheless inhabited by people, and are essential civic spaces. This is perhaps the core comment that we can make about Blood and Fire and Humaniora – whether provided by the state or organised by religion, the social safety net provided by health and welfare services produces and maintains ‘bare life’ across health conditions and amongst those living on low incomes.

-

Rosalind Nashashibi, Blood and Fire, 2003, 16mm, colour, sound, 7min, stills. Courtesy the artist and LUX, London -

Rosalind Nashashibi, Blood and Fire, 2003, 16mm, colour, sound, 7min, stills. Courtesy the artist and LUX, London

Numerous film works by Nashashibi from the mid-2000s consider closely, on the one hand, the issue of human perception and, on the other, that of anthropomorphism. Attributing human traits and forms to non-human entities is a common operation of the human gaze. Juniper Set (2004), filmed on a train, is a kind of portrait of a set of two empty seats. The seats side-by-side, with their patterned upholstery, stand in for absent bodies sitting together on a journey through suburbia. Park Ambassador, made the same year, depicts a totemic artefact in a municipal children’s playground in Glasgow. Resembling a tall human form with arms stretched wide, it is in fact a T-structure for what should be a swing. The lens becomes a surrogate of our own, lingering on the banal form long enough for us to anthropomorphise it and grant this non-human ambassador a sense of authority. From typical British suburbia, Eyeballing (2005) takes us to the urban sprawl of New York. Police officers in uniforms are seen standing around the doorway of the NYPD First Precinct. These human figures are contrasted with a landscape of faces, the non-human kind, provided by the city and its urban furniture and other objects. Faces appear in architectural facades, in standpipes, the head of an electric toothbrush within an apartment, or in a display of jewellery in a shop window. Juxtaposed with shots of police officers, the film can be interpreted as a comment on the police and surveillance state. These processes of personification appear as quintessentially human activities that are shaped by our relations to our surroundings, from the loneliness of the suburbs to the experience of the inner-city panopticon.

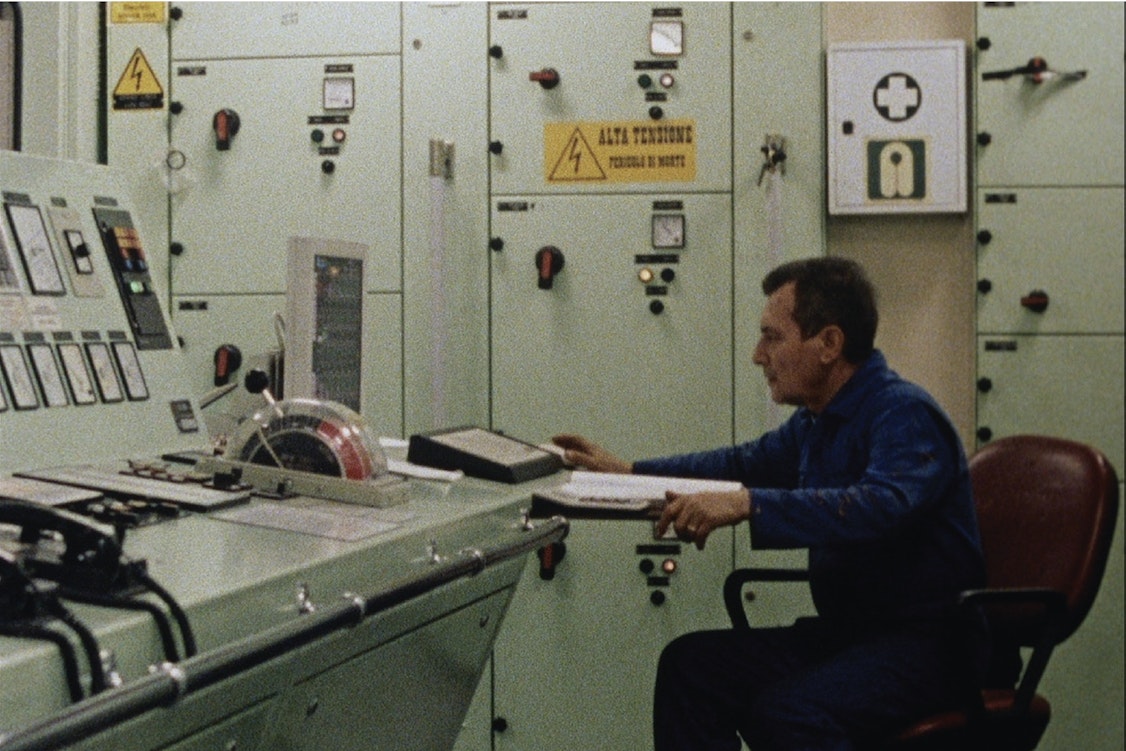

Nashashibi’s diptych Bachelor Machines Part 1 and Bachelor Machines Part 2 (both 2007) look towards the male subject. The titles make explicit reference to writer Michel Carrouges’s book The Bachelor Machines (1954), itself based on Marcel Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) (1915–23), and which inspired curator Harald Szeemann’s travelling exhibition ‘The Bachelor Machines’ (1975–77). Coined by Duchamp and further defined by Carrouges, Bachelor Machines refer to a complex model for desire and libidinal economy and forms of social and bodily technologies able, amongst other functions, to simultaneously encourage masculinity and yet emasculating men.07 Bachelor Machines Part 1 follows workers on a cargo ship – the Grimaldi vessel Gran Bretagna – sailing from Southern Italy to Sweden via Portugal, England and Ireland. The exclusively male staff confined on their long journey are together even during leisure or down time, playing cards, eating. Voices once again are captured as sounds rather than for verbal distinctiveness. Across twenty-five scenes, we witness a collective sense of solitude out at sea. On the ship, where life and work are indistinguishable except perhaps through administered time, the non-verbal body language between men changes. They undertake the grafting labour typically considered as men’s work, yet the posturing, the sexual dynamics, and other non-verbal significations of social situations found on land, no longer have a place when men are in such captive remedial existence.

-

Rosalind Nashashibi, Bachelor Machines Pt.1, 2007, 16mm, colour, sound, 30min, stills. Courtesy the artist and LUX, London -

Rosalind Nashashibi, Bachelor Machines Pt.1, 2007, 16mm, colour, sound, 30min, stills. Courtesy the artist and LUX, London

Bachelor Machines Part 2 functions, across two projections, on the one hand as a portrait of the renowned artist Thomas Bayrle along with his wife Helke (herself the subject of the related work Footnote, 2006), and on the other a sort of portrait of Nashashibi’s own artworks up until that point. It is perhaps also the first moment that a voice can be heard distinctively in one of Nashashibi’s works. Bayrle speaks, giving an apocalyptic vision of the world, stating at one point, ‘which through its abstract wishes of the rosary is heading us towards catastrophe’. Here, Bayrle refers to the apparatus of the church whose rhetoric that claims to liberate is ultimately one of violent punishment. The bachelor machine functions like a religious apparatus and enacts its patriarchal system of power, controlling bodies into subservience and emasculation. In contrast to the sharpness of Bayrle’s words and image is the second projection that configures many of Nashashibi’s previous works up until that point, yet here seen only out of focus. We can just about make out some individual works – the entrance of the NYPD First Precinct from Eyeballing, the lank figure of Park Ambassador. Blurred, the lens takes us somewhere more ambiguous, opening up various possible interpretations, one of them being, perhaps, the tension between religion and proxemics whose gaze is secular. Moreover, the way Nashashibi analyses people in their environment and their spheres of reality also reflects her peripheral position as an artist who yet shares the ability – with anthropologists, for instance – to ruminate on the relationships between men and machines, or the Mensch-Machine.

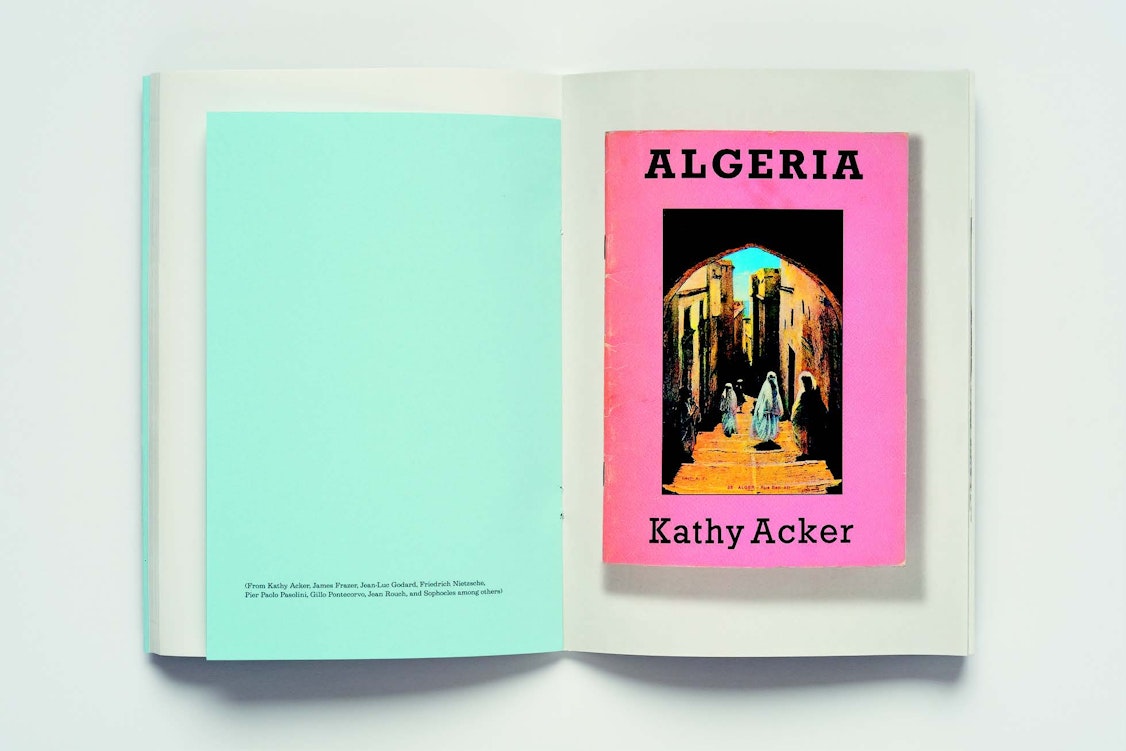

The editing strategy to bring two shots into proximity to create a space of interpretation in-between, as seen in Bachelor Machines Part 2 is also used by Nashashibi in her artist’s book Proximity Machine.08 Consisting of ten scenes, Proximity Machine presents a series of ‘static films’ constructed through sequencing found and re-photographed images from several sources. Each scene, or ‘machine’ as the artist has conceived them, is constructed by associating groups of images that invite one’s perception to draw and project visual and narrative connections. These fragments of narrative form a proxemics of sequenced images – each image is perceived in relation to those immediately preceding and succeeding it. Here, perception is active in response to this in-between-ness. The characteristics of each individual visual are drawn to the non-signifying interval of negotiation with one another. In one ‘machine’, from an image of a tea-stained video cassette box, follow the crater-flecked moon, an artwork by Hans Arp, a man holding a meteorite, a Hindu goddess holding the sun while astride a lion made of mingled people and animals. This sequence eventually leads to a scene from the Mahagonny-Songspiel opera in which a lady holds a large object over her head as she directs her gaze down towards a person lying on the ground beneath her.09 Proximity Machine is an artwork as book, an aesthetic tool for perceiving how individual images are shaped by their environment and their contextualisation.

-

Rosalind Nashashibi, Proximity Machine, 2007, published as part of ‘Singular Sociology’, a project curated for Book Works by Nav Haq, detail. Photograph: Edward Park. Courtesy Sara De Bondt and Book Works, London -

Rosalind Nashashibi, Proximity Machine, 2007, published as part of ‘Singular Sociology’, a project curated for Book Works by Nav Haq, detail. Photograph: Edward Park. Courtesy Sara De Bondt and Book Works, London

The growing tensions between politics and culture have a profound effect on our environment and the experiential dimension of our lives. Politics has become weaponised to the degree that it changes the environments where culture happens, thus complexifying proxemics. In this situation, even members from the same culture can even inhabit different ‘sensory worlds’. Subsequent works by Nashashibi such as Carlo’s Vision (2011) perhaps deal with this more directly, interpreting Pier Paolo Pasolini’s unfinished novel Petrolio as a way to talk about governance, state subterfuge, and their effects on society, particularly on class and sexuality. However, its mode is different, employing a more filmic narrative structure – a dialogue between two gods – and a more aestheticised visuality. Nashashibi’s film works from her first decade, however, form a unique body of work that possesses a remarkable lens for specific details that tell us something more precisely unspoken about the nature of our existence in our environments, at the intersection of the social, cultural and political spheres. Her observational lens has provided windows onto these sensory worlds.

We know more than ever, and certainly since the days of Hall, that culture is never static, and is in constant movement. For this reason, Nashashibi’s films might eventually take on the value of becoming time capsules. But they inform us of a new way of seeing that is conceptualised in relation to specific environments and located in a cultural impetus. When different sensory worlds collide, our proxemics become spaces of negotiation. By looking at competing sensory worlds, proxemics suggests new possibilities that might supersede the ethnological foundation of much identity-based politics, for much-needed post-identity liberalisms. More precisely, Nashashibi’s work draws our attention towards perception and proxemics as potential forms of liberalism – for producing freedom, openness and responsibility. As we comprehend from The State of Things, making adjustments to our environmental circumstances can shape new everyday realities. And to negotiate with and shape our environments means engaging in culture. And with the new awareness provided by such art – making visible the invisible – we are invited to use a radical imagination that can utilise proxemics in a way that can be transformational.

Footnotes

-

Edward T. Hall, The Hidden Dimension, New York and Toronto: Anchor Books and Random House, 1990 (1969), p.79. Emphasis original.

-

Ibid., p.1.

-

Ibid., p.2. Emphasis original.

-

Though ground-breaking in their contribution to cultural anthropology, Hall’s ideas of culture as something fixed and resistant to transformation, assimilation or integration are not without criticism. In his closing statement to the book, Hall writes that: ‘In the briefest possible sense, the message of this book is that no matter how hard man tries it is impossible for him to divest himself of his own culture, for it has penetrated to the roots of his nervous system and determines how he perceives the world. […] The ethnic crisis, the urban crisis, and the education crisis are interrelated. If viewed comprehensively all three can be seen as different facets of a larger crisis, a natural outgrowth of man’s having developed a new dimension – the cultural dimension – most of which is hidden from view. The question is, How long can man afford to consciously ignore his own dimension?’ Ibid., pp.188–89. Emphasis original.

-

Ibid., pp.79–80.

-

The film was made in reference to Thomas Mann’s novel The Magic Mountain (1924), which analysed progressive societies through the relationships between sickness and recovery that in Mann’s writing had become pivotal in their organisation.

-

See Michel Carrouges, Les machines célibataires, Paris: Arcanes, 1954; Harald Szeemann, Le machine celibi/Bachelor Machines, New York: Rizzoli, 1975.

-

Rosalind Nashashibi, Proximity Machine, London: Book Works, 2007. I was a guest editor of this book as part of a series of artists’ publications I commissioned for the publisher Book Works titled Singular Sociology.

-

Ibid., ch.7.