Kapwani Kiwanga is an intellectual artist. The methodologies of historical, scientific and theoretical research are the foundations of her artistic reflection. Although she became acquainted with these methodologies during her studies in anthropology and comparative religion at McGill University in Montreal (Kiwanga was born in Hamilton, Canada in 1978), it is through art practice that the primary sources she collects are manifested. In a 2017 interview, Carolin Köchling, curator at The Power Plant in Toronto, noted to the artist that ‘[t]here are concrete results from your research, which you transform into an abstract visual form. […] It would be interesting to hear you speak about this transformation and also about how research dictates aesthetics decisions.’01 Kiwanga replied:

This is a long road. First it is reading, reading and more reading. Then I think about a form that it could look or rather feel like. […] I always think about how this translates for the viewer. I think about the body going through the space, or the body encountering something. It is intellectual and at the same time corporal. 02

This elaborate approach is reminiscent of the conceptual practices of the 1960s and 1970s and in particular those of Adrian Piper. In 1971, based on Immanuel Kant’s philosophy, Piper produced Food for the Spirit and initiated a production that was simultaneously philosophical, critical and artistic. By creating points of junction between disciplines, it proposes modalities of reception that invite both a physical and mental investment on the part of the spectators. It can be said that the power relation that emerges between intellectual process and aesthetic production becomes a formal relation; it is in this conceptual and material tension that the aesthetic character is inserted. ‘What exactly is the aesthetic content of this work?’ was a question Piper posed in 1978 in relation to her installation Aspects of Liberal Dilemma, one of the first works of contemporary art to critique South African apartheid.03 This question begs reflection about the status of a committed visual proposal, whose critical or political function also exists through its aesthetic quality. Similarly, Kapwani Kiwanga confirms the need to produce a work that will be the result of a research process, that will be the place for the encounter between aesthetics and politics through form. Aesthetics is important for the artist as it also guarantees a kind of permanence. The artistic form is the vector of an ‘aesthetic gesture’ generated by a ‘very subjective political gesture’. Associating the spectators of an exhibition with this spatial and temporal experience is a way of insisting on the relationship established with the world.04 A world in which, to survive, one must find ‘exit strategies’.05 One understands, therefore, that these ‘exits’ are as much the lines of flight allowed by the creation of an artistic form as they are fugitive fictions based on a true history, a history of violence, dehumanisation, racism, slavery and colonisation. Kiwanga’s artworks concentrate in their sculptural, pictural, architectural, filmic and photographic body what they have learned from the survival methodologies of the maroon slaves and from the African anti-colonial revolts and independence. In their very form, Kiwanga’s works are inhabited by the history they strive to represent. It then becomes necessary to go back to the origins of this history to get closer to the artist’s research and to understand how form is a fiction only because it is the sounding board for buried memories, unhealed wounds and clandestine resistance. ‘Fiction is not the invention of imaginary beings. It is first and foremost a structure of rationality’, suggests philosopher Jacques Rancière.06

The work reveals what inhabits it in a burst of agency. One of the artist’s emblematic series is titled Glow (2019). It consists of human-sized sculptures, black monolithic columns made of wood, stucco and metal. Each has its own light, round or long, a bulb or LED tube inserted in the column. The Glow series was born of Kiwanga’s reading of Black studies scholar Simone Browne’s book, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness.07 In this book, Browne returns to what she calls ‘racializing surveillance’. She studies the techniques of people surveillance that reinforce discrimination and imprison bodies in a system that dates back to the period of transatlantic slavery. These are modes of surveillance that are still found in today’s world, notably in prisons and in the grids of cities. Kiwanga referred to the African-American activist Assata Shakur in the title of her 2017 exhibition in Toronto, ‘A Wall is just a wall’, and we could add to this what she wrote in her autobiography about her imprisonment in 1973:

[I]’d rather be in a minimum security or on the streets than in the maximum security in here. The only difference between here and the streets is that one is maximum security and the other is minimum security. The police patrol our communities just like the guards patrol here. I don’t have the faintest idea how it feels to be free. 08

This situation of permanent surveillance is at the heart of Browne’s study. In 2012, in an article titled ‘Everybody’s got a little light under the sun’, she explains one of the origins of her research:

I turn to Lantern laws in colonial New York City that sought to keep the black body in a state of permanent illumination. I use the term “black luminosity” to refer to a form of boundary maintenance occurring at the site of the racial body, whether by candlelight, flaming torch or the camera flashbulb that documents the ritualized terror of a lynch mob. 09

Also, Browne reminds us that on 14 March 1713, the Common Council of New York City voted in a ‘Law for Regulating Negro or Indian Slaves in the Nighttime’.10 In the third volume of New York Common Council’s book of law, one can read that ‘no Negro or Indian Slave above the age of fourteen years do presume to be or appear in any of the streets of New York City on the south side of the fresh water one hour after sunset without a lantern or a lit candle’. 11

Anyone affected by this law and who contravened it risked up to forty lashes, depending on the goodwill of the master or owner. Glow tells this story, and to study this body of work by Kiwanga, as with other pieces in which she interrogates these age-old issues of surveillance and racial discrimination, is also to understand that the sculptural form produced is a reminder of those black bodies walking in the dark, lit to remain visible. The fear that their skin colour might make them invisible in the dark and out of control is futile since, in the dark, white skin is no more visible than black skin is. To the fear of the ‘Black’ in the ‘dark’ is added the need to monitor every fact, gesture and movement. In the logic of a work of art created to preserve the memory of an event and ensure its continuity, we find the importance of producing a form, as literary critic Hortense Spillers reminds us in 2017 when she writes: ‘Formalism is, I believe, preeminently useful.’12 The sculptures of Glow, through their aesthetic qualities and formal simplicity, convey great poetry. They refer to the vision of fireflies as political allegory, which Aimé Césaire appropriated following Pier Paolo Pasolini by saluting their virtue:

Not to despair of fireflies

I recognize the virtue in that.

to wait to pursue them

to watch out for them too.

the dream is not to torch-pin them

not that they signal with unfold lights

I am moreover sure that reconversion occurs

somewhere for all those

who have never accepted the stupor of the air13

Sculptures from the Glow series were presented as part of Kiwanga’s solo exhibition ‘Safe Passage’ at MIT List Visual Arts Center in Cambridge, MA. With this title, the artist connects the history of eighteenth-century Lantern Laws to the means of escaping surveillance and plantation, the idea reminiscent of the freedom roads established at the same time in the frame of the Underground Railroad. Thanks to the latter, freedom seekers, such as the famous Harriet Tubman in the nineteenth century, helped thousands of captives escape the yoke of slavery. By shedding light on History, Kiwanga produces flashbacks and establishes trajectories in which ancient periods and current events coexist. Indeed, the former become contemporary through her formal work, which is conceived according to these ‘exit strategies’ that are themselves based on the ‘safe passages’ or on the ‘dark sousveillance’ as formulated by Simone Browne. As Tyrone S. Palmer reminds us in his review of Browne’s book:

In the face of widespread practices and technologies of racializing surveillance, Browne argues that racialized subjects perform acts of dark sousveillance, which entail ‘anti-surveillance, counter-surveillance and other freedom practices’. These dark sousveillance practices include, but are not limited to, forging freedom papers in order to escape enslavement, strategic racial passing, musical performance, and subverting the racist white gaze through artistic practice. 14

One could say that it is this process that guides Kiwanga’s entire production. With reserve and elegance, appropriating the vocabulary of her fellow minimalist and conceptual artists, she produces what Donald Judd called specific objects that conjure up events and imaginaries in keeping with that of her ancestors from the African diaspora. The lights of the sculptures sparkle in the night and remind us, as Sun Ra says, that ‘Just because a light is in the darkness does not make the darkness light’. 15

In May 2021, in the framework of her exhibition at Crédac, Contemporary Art Centre of Ivry, located in the outskirts of Paris where she lives, Kiwanga was in conversation with the author and art historian Zahia Rahmani whose work and research are based on a thorough analysis of colonial history. Rahmani sums up: ‘Artists open up paths. And these paths guide us towards the possibility to structure our thoughts differently than through the epistemological background that we have inherited and which was shaped by tragedies from which we must break away.’ 16One of these tragedies, forever marking the history of humanity with its violence, is the transatlantic trade, itself built on the foundations of the exploration and exploitation of colonised territories, in particular since 1492 and the ‘discovery’ of the New World by Christopher Columbus. In her exhibition at Crédac titled ‘Cima Cima’ in homage to the cimarrones, the so called ‘maroon’ slaves in Spanish, Kiwanga extends her research on plants and botany in relation to colonialism and slavery – ongoing research initiated in 2013 through her most famous work Flowers for Africa to which I will return later. At the heart of the exhibition ‘Cima Cima’, a room is dedicated to a kind of African rice called Oryza glaberrima. The history of this rice, closely tied to that of slavery, informs the artist’s reflection, who chooses to become one with the conditions created by the slaves to ensure their survival in nature – their refuge. As underlined by Kiwanga:

In “Cima, Cima”, there really is the idea of taking marooning gestures as possibilities to live with nature and affirm that it is not a separate thing. The maroons survived because they blended in with nature, which somehow protected them from the hostile and violent gaze that wanted to extract the person, the being of nature, and turn them into a working machine. 17

One of the foremost scholars of the history of rice in the context of slavery and colonialism, the Berkeley-trained American geographer Judith Carney, has been working since the 1990s on the migration of seeds and techniques from Africa to the Americas. In an essay published in 1998 in the journal Human Ecology, she wrote:

The glamerrima reported in Cayenne was collected from descendants of escaped slaves (maroons) who from the 1660s fled coastal sugar plantations for freedom in the rainforest. […] Maroons frequently cultivated rice in forest clearings and inland swamps. 18

One of the works in the exhibition, ‘Repository’ (2020), is a wall tapestry, its brown colours and abstract forms echoing West African motifs for which Kiwanga collaborated with Chicago-based textile artist John Paul Morabito. Morabito’s statement outlines an artistic process that explores queer cosmology, temporality and history. 19 When you get very close to the tapestry, one can see grains of rice made of crystal, inserted between the tightly woven stitches. Transparent, they are barely visible. The work is a symbolic representation of an oral history that has survived from generation to generation in various countries of the Americas, from Suriname to Guyana, Brazil (Amazonia), El Salvador and the United States (South Carolina). The grains of rice were originally carried by an African woman who hid them in her hair. Various sources reported by Judith Carney confirm the persistence of this belief, including colonial agriculture engineer André Vaillant’s 1948 survey of the Guyanese terrain, which mentions ‘the common legend among these blacks is that the rice came from Africa and that, for this reason, the women hid it in their hair’. 20

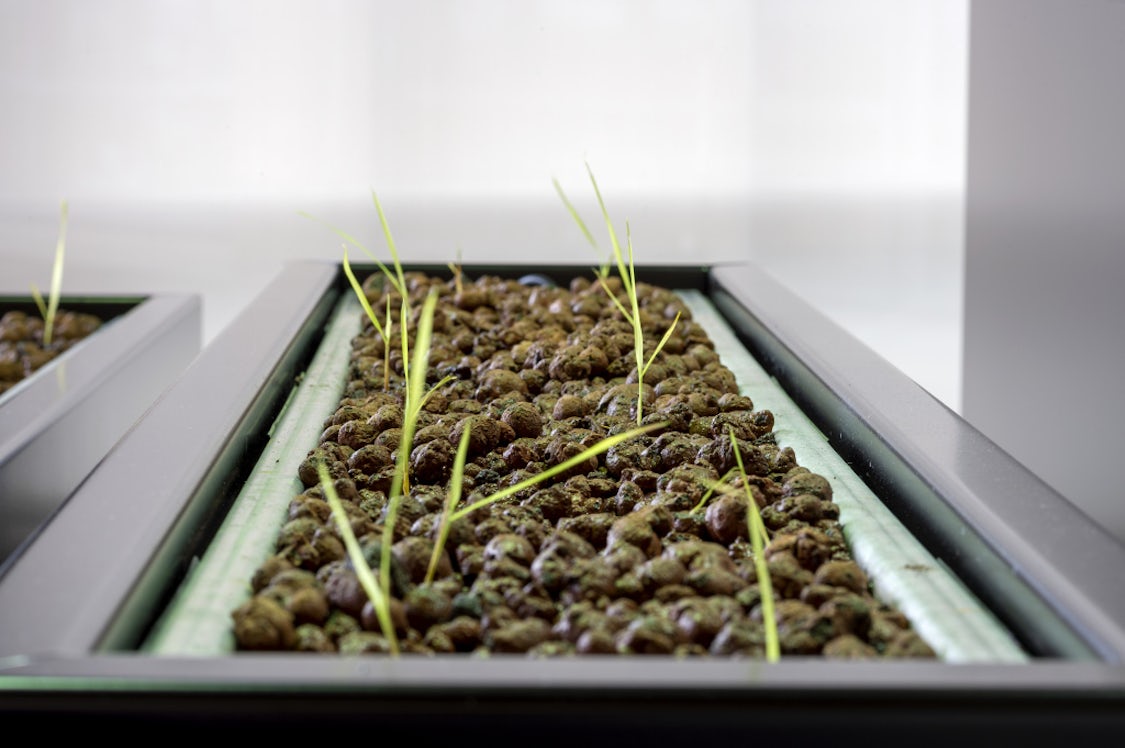

Even if Kiwanga does not offer full explanations through all her bibliographical references, it is almost certain that her work is conceived thanks to her exhaustive knowledge of this literature. Studying this work thus amounts to retracing, through her formal proposal, the intellectual and historical paths that have punctuated the history of this African rice transported by African women during the crossing of the Middle Passage. As an art historian reading these scientific accounts is to understand the artist’s creative process in reverse. What Carney repeatedly emphasises in her writings is that this history of ‘Black’ rice crossing the Atlantic through captive African women allows for a new historiography. This new historiography takes into consideration the points of view of the descendants of slaves or maroons, whereas until then it was the perspective of planters or explorers that was privileged. To suggest, for example, that this rice could have been transported by colonists from Asia was to deny the African origins of the cereal and, above all, the technical knowledge regarding its cultivation. For it was indeed the Africans who became slaves in the Americas who contributed their ancestral knowledge to the cultivation of a rice that had to adapt to another land. With regards to the plantation, the comments written by the masters systematically omit the logistical, mental and physical dexterity of their slaves. Through this work of recollection, Kiwanga contributed to this historiography, revisiting the history of agriculture and botany in a different way, going so far as to propose that she herself cultivate Oryza glaberrima in the art centre where she exhibits. In the installation Oryza, the thin, green and fragile shoots shiver as they emerge from the granulated soil and contrast with the black-painted galvanised aluminium tubs in which the rice is planted. The hardness of the smooth, cold, metallic support, an obvious reminder of the minimalist industrial sculptural forms created in the mid-1960s by Donald Judd (who speaks of the aggressiveness of the raw material in his famous essay ‘Specific Objects’ written in 1964), can be seen as a bulwark protecting nature. Moreover, as already mentioned, Kiwanga has long been interested in organic environments and their symbolism:

The plant or organic matter in general is an interest I have had in looking at different documents or references that are not textual or visual, but living. So I consider plants as witnesses or documents of history. Flowers for Africa is a series in which I look at the floral arrangements in photographs of the moments when African countries become independent.21

The photographs she refers to are the archives she finds during her research. By observing the role of ‘living witnesses’ performed by bouquets and floral ornaments during these important celebrations of the independence of a country that had been colonised until then, she chooses to re-actualise the event, even if in an ephemeral way. Working with florists in the places where she exhibited Flowers for Africa, she recreates the bouquets or decorations almost identically and presents them on plinths like sculptures. This work is traversed by an idea that repeats the role of the ceremonial still life seventeenth-century European paintings. Silent presences during African Independence ceremonies, these flowers assume a responsibility since their ‘testimony’ consists in being living and solemn traces of past times. By presenting fresh flowers destined to wither, Kiwanga pays homage to a historical moment – liberation from colonial rule – but also anticipates the danger of its disappearance and oblivion. The reiteration of these plinths, which host majestic floral compositions or simple bouquets, in different exhibition contexts, also refers to the presence of this type of ornamentation in religious settings, during wedding or mourning ceremonies. Each composition has its own symbolism, each flower its own allegorical charge. In the logic of research that can be taken even further, starting with Flowers for Africa, we could also interrogate the origins of the different flowers chosen for these decorative arrangements and the way in which floral art may or may not have been imported to Africa through colonisation. In the exhibition views, the red or pink gladiolus is noticeably often used. The gladiolus is a flower native to South Africa that was imported to Europe in the eighteenth century.22 The symbolism of flowers and their social uses (floral art is said to date back to ancient Egypt) would be another thread that could be drawn through the work of Kiwanga, which has a thousand facets to explore.

One might think that the artist’s relationship to colonial history is a way of working with her heritage and the way in which the heritage of the past feeds into the present. This may be too hasty an observation to make, forgetting that Kiwanga began her artistic practice by immersing herself in the Afrofuturist philosophy of Sun Ra, a powerful contemporary figure of emancipatory Black thought. With the creation of her fictional documentary Sun Ra Repatriation Project in 2009, and since 2011, her lecture-performances AFROGALACTICA-A brief history of the future, Kiwanga evokes the creation of the United States of Africa in 2058 and presents a series of visual, textual and sound archives describing the first space mission of this fictional country. Curator Yesomi Umolu offers a very interesting analysis of this work: ‘AFROGALACTICA is not just a mere exploration of Afrofuturism’s influences, it demonstrates that the possibility of framing Black subjectivity in the present and future lies at the heart of the archive.’ 23 The archive exhumed by Kiwanga is not only a memory of the past, it is also a memory of the future, that which consists in writing, through artistic forms, the histories to come, keeping alive the energy that defines them. Art carries within it an invincible, resilient and optimistic thought that allows poetic and political engagement to coexist, much like what Sun Ra says in ‘The Spontaneous Love’ in 1972:

It lives and blossoms like the flaming petals of a cosmic-flower.

It never dies because it is the idea of that which is to be

And that which is to be cannot die 24

(Translated from the French by Adeena Mey)

Footnotes

-

Kapwani Kiwanga and Carolin Köchling, ‘It can be broken down’ (A conversation between Kapwani Kiwanga and Carolin Köchling), in Kapwani Kiwanga: Structural Adjustments (exh. cat.), Toronto and Chicago: The Power Plant and Chicago University Press, 2017, p.73.

-

Ibid.

-

See the detail of the work in Adrian Piper, ‘The Real Thing Strange’, Adrian Piper, A Synthesis of Intuitions (exh. cat.), New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2018, p.84.

-

Sylvain Bourmeau, ‘Kapwani Kiwanga et Zahia Rahmani: “se frayer des chemins’’’, AOC media, Analyse, Opinion, Critique [online journal], 19 June 2021, available at https://aoc.media/entretien/2021/06/18/kapwani-kiwanga-et-zahia-rahmani-se-frayer-des-chemins/ (last accessed on 9 July 2021). A recording of the conversation in French is available at: https://credac.fr/en/artistic/cima-cima/table-ronde-no3 (last accessed 7 February 2022).

-

Ibid.

-

Jacques Rancière, Les Temps Modernes, temps, récit et politique, Paris: La fabrique éditions, 2018, p.14.

-

Simone Browne, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015.

-

Assata Shakur, Assata, an autobiography, Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2001 [London: Zed Books, 1987], p.60.

-

Simone Browne, ‘Everybody’s got a little light under the sun’, Cultural Studies, vol.26, no.4, 2012, p.546. (missing references)

-

Ibid.

-

Ibid., p.552.

-

Hortense Spillers, ‘Formalism comes to Harlem’, African American Review, vol.50, no.4, Winter 2017, p.692.

-

Aimé Césaire, ‘Virtue of Fireflies’, The Complete Poetry of Aimé Césaire (trans. Clayton Eshleman and A. James Arnold), Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2017, p.827.

-

Tyrone S. Palmer, ‘Review of Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness, by Simone Browne’, Souls, vol.18, no.2–4, 2016, pp. 479–80.

-

Sun Ra, ‘Black on Black’, The Immeasurable Equation. The Collected Poetry and Prose (ed. James L. Wolf and Harmut Geerken), Wartaweil: Waitawhile, 2005, p.80.

-

S. Bourmeau, ‘Kapwani Kiwanga et Zahia Rahmani: “se frayer des chemins’’’, op. cit.

-

Ibid.

-

Judith Carney, ‘The Role of African Rice and Slaves in the History of Rice Cultivation in the Americas’, Human Ecology, vol.26, no.4, 1998, p.337.

-

John Paul Morabito, ‘Statement’ [website], available at https://www.johnpaul-morabito.com/statement(last accessed on 9 June 2021).

-

André Vaillant, ‘Milieu cultural et classification des variérés de Riz des Guyannes française et hollandaise’, Revue internationale de botanique appliquée et d’agriculture tropicale, year 28, no.313–14, November–December 1948, p.522, available at https://www.persee.fr/doc/jatba_0370-5412_1948_num_28_313_6700 (last accessed on 9 July 2021). Judith Carney wrote on this migration in: ‘“With grains in Her Hair” Rice in Colonial Brazil’, Slavery and Abolition, vol.25, no.1, 2004, pp.1–27; see also Judith Carney and Richard Nicholas Rosomoff, In the Shadow of Slavery: Africa’s Botanical Legacy in the Atlantic World, Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 2009.

-

K. Kiwanga and C. Köchling, op. cit., p.76.

-

Matthew Crawford, The Gladiolus, A Practical Treatise on The Culture of the Gladiolus, with notes on its history, storages, diseases, etc. (appendix by Dr W. Van Fleet, 1911, addenda by J. C. Vaughan, 1921), available at https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/31237 (last accessed on 9 June 2021).

-

Yesomi Umolu, ‘Reenacting histories’, in Kapwani Kiwanga: Structural Adjustments, op. cit., p.6