There are few curators of contemporary art who have been as widely discussed and as generally admired as Harald Szeemann (1933–2005). 01The tireless director of the Kunsthalle Bern in Switzerland from 1961 to 1969, Szeemann later founded the Agentur für Geistige Gastarbeit, a self- mockingly titled office (or ‘Agency for Intellectual Guest-Work’, which uses the term for migrant labour in German-speaking countries) for independent projects that created a blueprint for subsequent generations of freelance curators and cultural producers everywhere. The rough coordinates of his life and career are well known: after early experiments as a one-man theatre company and a dissertation on modernist book illustration, he was selected as successor by the outgoing director of the Kunsthalle Bern, Franz Meyer, which made him, at the age of 25, the youngest director of an art institution in Europe at the time. The Kunsthalle Bern was highly regarded for its authoritative programme of individual exhibitions of modernist artists such as Paul Klee, Alberto Giacometti and Henry Moore, and Szeemann developed this series by organising solo exhibitions by artists of his time, such as Otto Tschumi, Robert Müller and Roy Lichtenstein. But he also presented a series of speculative group exhibitions about diverse topics such as ‘Bildnerei der Geisteskranken’ (‘Artistry of the Mentally Ill’, 1963), ‘Formen der Farbe’ (‘Shapes of Colour’, 1967), ‘Science Fiction’ (1967) and ‘12 Environments: 50 Jahre Kunsthalle Bern’ (‘12 Environments: 50 Years Kunsthalle Bern’, 1968), and survey exhibitions such as ‘Junge Kunst aus Holland’ (‘Recent Art from Holland’, 1968) and ‘22 junge Schweizer’ (‘22 Young Swiss Artists’, 1969). 02

However, it was not until 1969 that he curated the exhibition that would establish his professional reputation and that has since become celebrated as the exhibition most closely identified with the artistic experiments of the late 1960s.

‘When Attitudes Become Form (Works – Concepts – Processes – Situations – Information)’, which was programmed to take place from 22 March to 27 April 1969, 03 brought Szeemann international recognition and much publicity, but it also caused him to leave his job at the Kunsthalle Bern, incidentally launching his career as a freelance curator (or ‘exhibition maker’, ‘Ausstellungmacher’ in German; the formulation that he himself preferred). Shortly thereafter he moved to Kassel, where he took over the position of General Secretary of documenta 5, then back to Bern and his summer house in Italy, until he settled in 1978 in a small village in the Swiss Alps, Tegna, which would become the headquarters of his freelance activities for the rest of his life.

During the 1970s and early 80s, Szeemann developed his most iconic projects, starting with his controversial documenta 5 (1972). Under the title ‘Befragung der Realität: Bildwelten heute’ (‘Questioning Reality: Image Worlds Today’), this multi-part exhibition brought together hyperrealism with kitsch, religious painting and the art of the insane, and introduced one of his lifelong concerns: the ‘Individual Mythologies’ of artists. In 1973, Szeemann began working on a project he called the ‘Museum of Obsessions’, which would continue to occupy him for the rest of life and would be the intellectual umbrella under which all later activities would appear (the Agentur für Geistige Gastarbeit would become the administrative arm of the Museum of Obsessions, while Individual Mythologies would feature as one segment of the Museum). 04Under this banner, Szeemann organised a series of visionary group exhibitions on turn-of-the century utopian artists, dancers, doctors, nudists and ‘Lebensreformer’ (‘life reformers’) starting with ‘Junggesellenmaschinen/Les machines célibataires’ (‘The Bachelor Machines’, 1975–77) and ‘Monte Verità: Le mammelle della verità’ (‘Monte Verità: The Breasts of Truth’, 1978–81). The apotheosis of this period of historical reinvention, a radical blending of artistic and social experiments, literary and musical avant-gardism and all things synaesthetic, was the exhibition ‘Der Hang zum Gesamtkunstwerk: Europäische Utopien seit 1800’ (‘Tendency towards the Gesamtkunstwerk: European Utopias since 1800’, 1983), which focused on several moments in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries when artistic invention, erotic desire and utopian social impulses came together to propose a radically expanded and inclusive vision of life and creativity. It is these exhibitions – together with a string of biennials and larger thematic shows curated in the last decade of his life – that confirmed Szeemann’s standing as a curatorial auteur. But the early provocation of ‘When Attitudes Become Form’, which led to widespread protest in the local press and community, 05 the cancellation by his board of a planned Joseph Beuys exhibition, and finally Szeemann’s resignation from the directorship of the kunsthalle in the summer of 1969, was the event that launched his international career as a curator of contemporary art.

‘When Attitudes Become Form’ marked the end of a decade of extremely fertile innovation and experimentation that had great influence on the visual arts. In short order Pop art and Fluxus, Minimalism and post- Minimalism, Conceptual art, Land art and Arte Povera transformed the discourse on the nature of art and its materials, questioning how and by whom a work of art can be made, where a work of art can exist and even whether it needs to exist as a physical object at all. In the decade between 1959 – when documenta 2 was one of the first large-scale international exhibitions exclusively dedicated to the art of the present day – and 1969 – when ‘When Attitudes Become Form’ opened – contemporary art had tested almost every limit and redefined nearly every relationship that existed between artist and audience, source material and finished work, idea and execution, and object and contextual surrounding. In the late 1950s, contemporary art was still a game of (predominantly) male artists and gentleman dealers, of connoisseur museum directors and taste-making critics, all grouped in a few recognised centres of classic culture and working almost exclusively in the conventional media of painting and sculpture. By the time the Bern exhibition opened in March 1969, it not only presented art made by a different cast of characters and utilising radically different means of production, it was also part of a larger art network that included gallery shows, temporary festivals, an emerging fair system and a surprising number of exhibitions in public institutions introducing the most significant characteristics of new art in the 1960s to a wide audience in both Western Europe and North America. Most of these exhibitions focused on one specific aspect of this new art, in an attempt to understand or define a new tendency or direction: the 1966 exhibition ‘Primary Structures’ engaged with what now is generally understood as Minimal art;06 in the same year ‘Eccentric Abstraction’ presented work that is now widely described as post- Minimal; 07 the exhibition ‘Arte Povera’ at the Galleria La Bertesca in Genoa (1967) and the event ‘Arte Povera + Azioni Povere’ centred on the Antichi Arsenali di Amalfi (1968) presented Italian artists grouped under the term Arte Povera (it also included the Dutch artists Jan Dibbets and Ger van Elk and the British artist Richard Long); 08 and the exhibitions ‘January 5–31, 1969’ and ‘March 1969’ helped define Conceptual art through their innovative approach of de-emphasising the material presentation in favour of the publication or, as in the ‘March’ show, making the publication effectively the site of the exhibition. 09 Szeemann’s exhibition was different in that he tried to resist any one single description or definition, and instead to provide a more encompassing overview of the different artistic tendencies that were emerging after the success of Pop art and Minimal art. ‘When Attitudes Become Form’ brought together works that might have been discussed under a number of different headings – Minimal art, Conceptual art, Arte Povera, Earth art and so on 10 – and, for the first time, staged an encounter between the work being produced in the US and parallel developments across Western Europe.

But ‘When Attitudes Become Form’ was not the only exhibition that tried to capture the larger contours of the art of this moment. Less known today, yet equally prominent at the time, was an exhibition with which ‘When Attitudes Become Form’ shares a considerable history: ‘Op Losse Schroeven (Situations and Cryptostructures)’ was held at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam from 15 March to 27 April 1969, opening just one week before the Bern exhibition. 11 Organised by Wim Beeren (1928 – 2000), then the head of the painting and sculpture department at the Stedelijk Museum, ‘Op Losse Schroeven’ had much in common with ‘When Attitudes Become Form’ and referred to the Bern exhibition on the title page of its catalogue. 12 Both exhibitions included many of the same artists, 13 were reviewed together in several publications and were perceived as companion shows by contemporary critics. 14 They shared organisational resources (Szeemann had a larger budget and routed many artists via Amsterdam so that they could install their works for ‘Op Losse Schroeven’), as well as intellectual and conceptual traits. However, despite the remarkable overlap of artists, travel schedules and studio visits, and despite the fact that Szeemann’s notes on organising ‘When Attitudes Become Form’ were published in the catalogue for ‘Op Losse Schroeven’, 15 the two exhibitions have fared rather differently in their long-term reception, with Szeemann’s show claiming a considerably larger share of the historical record. Due to its somewhat longer roster of artists, better funding and publicity, catchier title, and in no small measure due to the subsequent prominence of Szeemann himself, ‘When Attitudes Become Form’ has assumed the role of the representative exhibition of that moment, while ‘Op Losse Schroeven’ has almost disappeared from history, its reputation largely confined to Dutch-speaking historians and audiences. Beeren’s lack of international celebrity, a result of his having spent most of his professional career in the Netherlands, may partly explain this historical disparity, and other reasons for the historical success of the Bern exhibition will emerge at further points in this text. But I believe that only in tandem with ‘Op Losse Schroeven’ can ‘When Attitudes Become Form’ be fully understood. When the two exhibitions are seen together, the differences in choice and temperament that guided their respective curatorial ambitions become clear, and one can more easily discern the particular reading that each represents. Moreover, through a comparative study one gains deeper insight into the complexity of the task taken on by these two curators, working to survey the radical new art that was emerging in the late 1960s.

When the two exhibitions are directly compared, perhaps the most significant difference is the role each curator identified for himself in regard to the exhibition. Whereas Beeren, from the very beginning, sought to observe changes in materials, contexts and fabrication processes, and to develop a new terminology and classification for these observations, Szeemann responded to the changes in artistic practice by inviting artists to replicate their working methods within the space of the gallery. For Szeemann, the curator was, to borrow a description coined by Hans Ulrich Obrist, a ‘catalyst’ enabling artistic production, whereas Beeren, at least at the beginning, saw his role as that of a historian, noting developments and analysing current artistic production from a perspective of past achievements. 16 And yet, without aiming to overturn the general direction of each curator’s working method and objective, some of the artists involved have suggested, in retrospect, that Beeren’s exhibition in fact might have been more closely aligned with the artists’ intentions than generally assumed, while Szeemann’s emerges as more attentive to the concerns of the galleries that represented many of them. 17 Moreover, despite the curators’ collegiality and their remarkably similar travel schedules, their different backgrounds and predilections resulted in some subtle and not so subtle differences in the choice of artists, and in the selection, installation and interpretation of works. I hope that the nature of these differences and the impact they had on the shape of the respective exhibitions will become apparent in what follows, through a close inspection of the genealogies of the two exhibitions, as well as through an analysis of their material and discursive manifestations.

Above all, I hope this comparative approach will help to recalibrate the historical relevance of ‘When Attitudes Become Form’ and ‘Op Losse Schroeven’. By this I do not mean to suggest that Szeemann’s landmark exhibition is undeserving of the historical importance it has been ascribed; rather, I aim to make clear how Szeemann’s achievement cannot be separated from other similar efforts at the time, and that Beeren’s contribution will become better known and his efforts duly acknowledged. For although Beeren’s career path up to this point had been significantly more predictable and conventional than Szeemann’s – Beeren was the product of a traditional art-historical education and largely formed inside the museum, while Szeemann came to the kunsthalle from the theatre, cabaret and the experimental literary scene, albeit with a degree in art history – his intentions were as much shaped by the new art he encountered as Szeemann’s. Through his contact with artists Beeren also found himself challenging his institution from within, and expanding his understanding of the role of art in the world. And just as Szeemann left the Kunsthalle Bern after ‘When Attitudes Become Form’ so Beeren chose to leave the Stedelijk Museum shortly after ‘Op Losse Schroeven’, to curate the sixth edition of the open-air arts festival Sonsbeek, based in Arnhem, the Netherlands, in 1971. Beeren’s experience of working on ‘Op Losse Schroeven’ set him on a very different path from Szeemann’s and he was perhaps more immediately dedicated to working with contemporary art and artists, especially those interested in taking art out of the museum and into the landscape, while Szeemann’s interests turned increasingly towards a curatorial practice involving the creation of exhibition scenarios and the exploration of the Individual Mythologies mentioned earlier.

These two exhibitions, opening within a week of each other, represent two parallel but distinct responses to the art of their time, two ways of understanding a moment in which the nature of art production was changing radically and the traditional function of the exhibition space was being challenged by the demands of artists. Through a close examination of the histories of ‘Op Losse Schroeven’ and ‘When Attitudes Become Form’, and of their material and discursive manifestations, we shall be able to trace two distinct curatorial trajectories, two ways of thinking about exhibition making. In doing so, we shall be able to reflect on the ways in which new art interacts with its audiences and achieves historical longevity through the medium of the exhibition.

The Paths Towards the Exhibitions

By 1968, after seven years as Director at the Kunsthalle Bern, Harald Szeemann had gained a reputation for making cutting-edge thematic exhibitions and, above all, for bold statements. That his flair should be recognised by pioneering protagonists in the nascent arena of international art sponsorship should not come as a surprise, but the sequence of events that unfolded in the summer of 1968 is nonetheless remarkable. On 13 July 1968, Nina Kaiden, the director of Fine Arts for the New York Public Relations agency Ruder & Finn and an important consultant for emerging corporate art collections and philanthropic activities in the US, paid a visit to Szeemann at the kunsthalle. 18 Imagine the scene: she entered a small crowded basement office without a typewriter or fax machine, and stuffed with a ‘totally over-laden, white-painted bookcase whose shelves had begun to bend beneath the accumulated intellectual weight’, where Szeemann sat, clad in ‘white jeans, Manchester jacket and canvas shoes’. 19 Around him, workers were busy in their final preparations to wrap the entire building with 2,500 square metres of reinforced polyethylene, secured with 3,000 metres of nylon rope – Christo’s first-ever wrapping of an entire building; a project that unfolded over the coming days as part of the exhibition ‘12 Environments’, on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the kunsthalle. 20 And imagine the proposal: on behalf of her client Philip Morris, Kaiden offered Szeemann substantial funds to organise an exhibition of new art at the kunsthalle, under the condition that it would travel elsewhere. 21 Szeemann’s response was enthusiastic: ‘I said, “yes, of course”. Until then I had never had an opportunity like that. Usually I wasn’t able to pay shipping costs from the States to Bern, so I cooperated with the Stedelijk, which had the Holland American Line as a sponsor for transatlantic shipping, and I only had to pay for transport in Europe. In this way I was able to show Jasper Johns in 1962, [Robert] Rauschenberg, Richard Stankiewicz and Alfred Leslie, and many more Americans later on. So getting this funding for “Attitudes” was very liberating for me.’ 22 But the concept for the show was yet undefined. A week or so after the opening of ‘12 Environments’ and the meeting with Kaiden, on 22 July 1968, Szeemann travelled through the Netherlands with his friend and colleague Edy de Wilde, the director of the Stedelijk, to select artists for a collaboration between their two institutions comprising two exhibitions, one presenting young artists from the Netherlands, the other young artists from Switzerland. 23During the trip Szeemann expressed interest in the new art being made on the West Coast of the US, 24 but de Wilde said he was already working on a similar exhibition:

‘Edy said, “You can’t do that. I’ve already reserved the project for myself!” And I responded, “Well, if you reserved that idea when’s the show?” His was still years down the road, but my project was for the immediate future.’ 25 That day they were at the studio of the Dutch painter Reinier Lucassen, who had asked his studio neighbour and occasional assistant Jan Dibbets to help out with the visit and act as interpreter. After visiting Lucassen, Szeemann and de Wilde also made a brief visit to Dibbets’s studio, where they encountered two tables: one with neon coming out of the surface, the other covered with grass – which Dibbets watered during their visit. Apparently taken by the radicalism of Dibbets’s ‘simple’ experiment, Szeemann later that evening turned to de Wilde and proclaimed ‘I know what I’ll do, an exhibition that focuses on behaviours and gestures like the one I just saw.’ 26 Abandoning the idea of an exhibition of art from the West Coast, Szeemann speculated that Dibbets’s approach to art-making was representative of a new generation of artists, and he quickly began to gather information about others whose works and methods might be understood in a similar light. In the diary he wrote to record the preparation of ‘When Attitudes Become Form’, Szeemann identifies this moment as the germination of the project. But the immediate question about how to represent the work of artists who resisted producing conventional art objects – or rather the question of how to make it clear that they were presenting their ideas instead of making works of art for exhibition – was not lost on Szeemann: ‘In the beginning was Dibbets’s gesture to water a lawn on a table. But you cannot exhibit gestures.’ 27

In addition to showing them his work, Dibbets had also told Szeemann about other artists working in a similar vein, among them fellow Dutch artists Marinus Boezem and Ger van Elk, the English artist Richard Long and the Italian Piero Gilardi. In their work these artists incorporated new materials such as rubberised plastics and fibreglass, or declared simple gestures and processes – such as taking a walk in the countryside or observing the daily changes in weather – to be art. They knew each other (Dibbets and Long had studied together in London, van Elk had written an introduction for the Dutch translation of a text by Gilardi) 28 and they felt a kinship despite the apparent diversity of styles and practices.

By August 1968, Szeemann had reported back to Kaiden about his idea to present ‘a confrontation of the artists of the Cold Poetic Image, who had already hinted at the new problems in their work ([Marcel] Duchamp as father, then [Öyvind] Fahlström, [Carl] Andre, [Michelangelo] Pistoletto, [Dan] Flavin), with the “new” artists’. 29 The following month, as research and preparations for the exhibition ‘Recent Art from Holland’ at the kunsthalle took over, Szeemann seems to have already moved away from his initial idea and abandoned the historical perspective in favour of presenting only the ‘new’ artists (of the figures quoted as influences, only Andre made it into the exhibition, with Pistoletto listed in the catalogue as being represented by ‘Information’). By October he had assembled an initial working list of fifty artists, which he submitted to Philip Morris for approval on 30 October, and on 5 November a telegram from New York announced: ‘Exhibition idea accepted.’ 30 And, as Carel Blotkamp has noted in his account of the Dutch art scene of the late 1960s, it was at this time (during the opening of the exhibition ‘Recent Art from Holland’ on 2 November 1968 at the Kunsthalle Bern) that Szeemann had another discussion with Dibbets, van Elk and Boezem, arriving at, as Blotkamp speculates, the final form of ‘When Attitudes Become Form’. 31 On 10 November, Szeemann learned that an exhibition scheduled for March and April 1969 had to be postponed,32 and immediately began to conceive the Philip Morris-sponsored exhibition for this slot, only five days after the confirmation from Kaiden that his proposal was accepted and barely five months before the opening of the show. The same week, de Wilde came to Switzerland to conduct studio visits for the exhibition presenting Swiss artists in the Netherlands, and Szeemann informed him of his planned project. A week later, Szeemann began to travel with breakneck speed to visit the artists for his exhibition, starting with another trip to the Netherlands, in which he did a follow-up studio visit with Dibbets as well as visits with Boezem, van Elk and Gilardi (the latter of whom had travelled to the Netherlands to participate in the conversation and, together with van Elk, met Szeemann at the train station). Later that month, Szeemann travelled to Germany and, for most of December, crisscrossed the US, with stops in New York, New Jersey, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Dallas and Chicago. And just as the year 1969 was beginning, Szeemann was off to Italy, with a final round of travels to London, Munich, Cologne and Düsseldorf.

It is important to note that Szeemann seems to have had his initial direct contact with Wim Beeren about their respective exhibitions less than two months before these opened. This is surprising given the amicable relations between them, the close contact they had with many of the same artists and given Szeemann’s friendship with Edy de Wilde, who, as the director of the Stedelijk Museum, had to approve Beeren’s proposal for ‘Op Losse Schroeven’. According to Szeemann’s meticulous travel diary, the two curators met up for the first time in the process of organising their shows in Amsterdam early in February 1969, and by the end of that month Szeemann had submitted his diary to the Stedelijk Museum for publication in the ‘Op Losse Schroeven’ catalogue. ‘When Attitudes Become Form’ opened in Bern on 22 March 1969. It was formed as an idea over the course of a few summer months, and seems to have derived its extraordinary sense of currency from the speed with which it was put together – finalised in just three months of intensive international travel.

—

In contrast, the origins of ‘Op Losse Schroeven’ follow, at least at first, a more protracted and conventional trajectory. Early in September 1967, almost a full year before Szeemann began working on ‘When Attitudes Become Form’, Wim Beeren met Jan Dibbets, who had just returned from his studies at St Martin’s School of Art in London. Beeren had observed that more and more artists were experimenting with new materials and found objects, and he was considering proposing that the Stedelijk Museum make an exhibition to look at the development of such practices, tracing a lineage from Duchamp’s readymades and Yves Klein to the most recent practices of such artists as David Medalla (especially his sculptural experiments with sand and foam). In an interview in 1995, Beeren recalled:

Originally I was concerned with the change in the materials of the objects… Materials were important then because you could produce an artwork that made a totally different statement with them… The presentation and the status of the artwork as well as its site were also strongly influenced by the materials. Partly through their increased size, works of art became pretty conspicuous things in themselves. Intransigent and ineluctable, they were associated with situations in museums and galleries. They were also to a high degree transportable market products. The new work of art created or impacted on a situation. People literally went off into the desert. 33

What began with a concern for new materials soon developed for Beeren into an acute interest in the new sites of art and the placement of objects in contexts other than conventional gallery spaces. The artists of Earth and Land art, in both the US and Europe, would become of some importance to him, but initially he looked close to home: to the work of his Dutch contemporaries. As he said:

I remember that I was visiting Jan Dibbets at his house in Enschede at the time, and that I was expecting paintings from him. But he was already off on another track and told me that he was going to Frankfurt the next day to take part in the exhibition ‘Dies alles Herzchen wird einmal dir gehören’. 34

Shortly thereafter, in late September or early October 1967, Beeren made a studio visit to Ger van Elk in his Velp studio near Arnhem accompanied by the then Paris-based gallerist Ileana Sonnabend, to look at his sculptures made using polyurethane. Sonnabend, observing a certain similarity between van Elk’s works and those of artists working in Italy at the time, suggested to van Elk that he make contact with Piero Gilardi, the artist and critic who, it turned out, was exhibiting in the Netherlands, at Galerie Mickery in the village of Loenersloot, near Utrecht, from 8 October to 6 November 1967. 35 By the same time a year later, van Elk had written the introduction to the Dutch publication of Gilardi’s essay ‘Microemotive Art’. 36 And by the end of 1967 Dibbets had also introduced Beeren to the work of his fellow London student Long.

For Beeren, the works of Dibbets, van Elk, Long and others directly tied in with his plans to organise an exhibition about new materials in art. The Stedelijk Museum archive holds notes and early sketches for the exhibition concept, which point to an acknowledgment of the historical importance of the readymade and are structured around the idea of the object in art. Some notes espouse different categories, such as ‘Collage’, ‘Object/Readymade’, ‘Object/Sculpture’, ‘Assemblage’, ‘Environment’, ‘Happening’ and ‘Situation’, while others indicate an attempt to break down these categories further into materials such as gas and light, neon (for which Lucio Fontana is listed as an example), mirrors, fat and so forth.37 All indicate Beeren’s desire to explain the most recent developments as part of a longer historical trajectory, and his determination to construct a map of relationships and categories that would illuminate the emerging art of the time.

Over the course of the following eighteen months, Beeren’s proposal for a show about new materials would slowly evolve into the exhibition ‘Op Losse Schroeven’, a title that borrows a Dutch idiomatic expression referring to a construction that has come loose or a situation that has become unstable. The final concept takes Beeren’s initial interest and renders it more complex by expanding some of the categories that are already present in the earliest drafts (albeit as more marginal concepts, such as ‘Situation’ and ‘Environment’), and placing the exhibition squarely within the contemporary arena. In the process of his research, especially through his contact with artists in Italy and his understanding of Long’s practice (and his reading of Land art through Long), Beeren expands his earlier object- centred categories into notions of site-specificity and ‘situation art’, 38displacement and material transformation, as well as ‘change as a formative principle’ – all informed by process and context, rather than material and objecthood. 39

Starting in summer 1968, around the same time Szeemann was visited by Nina Kaiden, Beeren began to make a more serious list of contacts for travel and studio visits. On 6 August 1968, van Elk wrote to Beeren urging him to visit several artists on Gilardi’s recommendation, after he had learned that Beeren was planning a trip to see the Arte Povera artists in Italy. And around the same time, Edy de Wilde informed Beeren about a number of artists working in Turin (including Gilardi) asking: ‘I got the feeling their work would fit in with the object project. Do you know about them?’ 40 At this point, Beeren had already decided to include in the exhibition the Dutch artists he had visited nine months earlier, and was considering which other Italian artists (besides Gilardi) it would make sense to invite. That autumn Beeren travelled to Turin and other cities in Italy, and a document in the Stedelijk Museum archive lays out a further travel schedule: meetings with van Elk, Dibbets and Boezem between 7 and 19 October 1968; England from 29 to 31 October; US approximately from 1 to 11 November; and Germany in early December. The first draft of an exhibition concept submitted to de Wilde that focuses on situations – titled ‘Cryptostructuren en Microemoties’ (‘Cryptostructures and Microemotions’) – is dated 25 December 1968, and the accompanying note suggests Beeren was departing for Italy the same day. Soon after Christmas, Beeren seems to have arrived at his title, ‘Op Losse Schroeven’, 41 and by 21 January 1969, the first batch of invitation letters went out to artists requesting them to contribute works to the exhibition, and, in some cases, also information and drawings for a special section in the catalogue. At the beginning of February 1969, Szeemann came to visit Beeren in the Netherlands, and the two exhibitions finally crossed paths.

—

One of the most perplexing questions to anyone considering these two exhibitions in detail is why their two curators appear to have kept their research to themselves for so long and not shared information. Not only the similarity and proximity of sources and resources – the artists who acted as first informers, the essays consulted, 42 the gallerists involved – but also the curators’ amicable relationship suggests that it must have been decidedly more difficult to withhold information than to reveal it.

In recent conversations conducted during the research process for this book, several contemporaries of the curators have remarked on this peculiarity. Van Elk and Dibbets, the Dutch art historian Rini Dippel and Beeren’s former assistant Ank Marcar have all speculated that the acquaintance between Szeemann and Beeren was precisely the reason why both kept their cards so close to their chests. Among the artists, word had spread pretty quickly that both curators were in effect conducting the same research: pursuing largely the same artists through the same cities and galleries. Indeed van Elk has made the curious suggestion that the physical similarity of the two men – each was solidly built, bearded and bohemian in style – made it interesting for an artist to work with them both, as their quickly staggered studio visits turned into a kind of performance; that of a curator chased by his doppelgänger. 43

Even after they had informed each other of their plans, both curators would continue to work quite independently from each other, suggesting that they were particularly fierce about their own authorial efforts. In an interview in 2003, Szeemann reflected on the parallel and well-concealed respective research, but even 35 years later, subtle rivalries persist:

I didn’t know that Wim Beeren wanted to do the same thing as me in Amsterdam. De Wilde should have told me. We’d have done it together. I even gave all the artists the chance to come via Amsterdam, because Beeren insisted on starting the exhibition a week before me. […] In the end, people talked much more about mine, even though his started a week before me. People talked about it more, because it was more anarchist. Obviously there were almost the same artists as its starting point. In Bern, the exhibition took the artists as its starting point. There weren’t rooms with works hanging in them. It was fairly chaotic; it was more innovative. In Bern, you could do a lot more things. Everyone could do what he wanted. At the Stedelijk, you couldn’t take a bit of wall down for [Lawrence] Weiner’s intervention, or destroy the pavement for [Michael] Heizer’s work, or make [Richard] Serra’s lead, or have the whole kunsthalle put under radiation by [Robert] Barry. 44

In fact, Beeren’s restrictions were not as severe as Szeemann suggests. Heizer excavated the pavement in Amsterdam, Serra splashed lead against the façade of the museum, and Dibbets, van Elk and Boezem all made interventions into the fabric of the museum as well. And Beeren did follow a model of artistic collaboration and participation in decision-making. But crucially, Beeren did not have direct control of his institution, as Szeemann did in Bern. Further, the Kunsthalle Bern was a relatively small organisation, with exhibitions generally rotating every two to three months and no collection, whereas the Stedelijk Museum was a national institution displaying an internationally recognised collection of classic modern and contemporary art, alongside a full programme of temporary exhibitions. Amongst a smaller staff team and in a smaller venue, decisions could be taken more quickly, and as both the director and curator Szeemann had considerably more freedom than Beeren, who reported to and needed permission from his director, de Wilde.

Szeemann’s comments in turn point to a more significant question about de Wilde’s central yet conflicted role as interlocutor to both curators during the entire process. A friend and confidant of Szeemann, he was one of the first people to learn about Szeemann’s ideas and was kept up to date about every step in the exhibition’s development. And as Beeren’s director, he knew about his plans for an exhibition about ‘new materials’ from the very beginning and by August 1968 had already recommended artists to Beeren for his ‘object project’. 45 What remains puzzling, of course, is why de Wilde appears not to have informed either curator about the plans of the other. There is plenty of evidence that de Wilde was not altogether convinced that this new art in fact deserved an exhibition. Trained as a lawyer and initially working for the government in recovering artworks stolen during World War II, in 1946, at the young age of 26, he took over the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, where he created a sensation when he purchased an early Pablo Picasso painting for a then colossal sum of over 100,000 Dutch guilders. At the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, where he was appointed Director in 1963, de Wilde continued to pursue his interest in Modernism but was also able to embrace Pop art and artists such as Willem de Kooning and Barnett Newman. But de Wilde’s love for painting, especially of the École de Paris, did not extend much to sculpture, or to the more advanced experiments in materials and installations that Beeren proposed to him. Those involved in the organisation of ‘Op Losse Schroeven’ have recalled de Wilde’s initial reluctance. 46 As Gijs van Tuyl, Director of the Stedelijk Museum between 2005 and 2009 and an intern there in 1969, remembers: ‘Beeren had to work very hard to convince him, after he returned home from a trip in the US. He had met Dibbets and Gilardi. Then he could push it through. It was a big splash. finally he got his way and he could do it.’ 47 According to Marcar, who was a fellow member of staff at the museum and edited the catalogue of ‘Op Losse Schroeven’, a substantial part of the quarrels between Beeren and de Wilde – beyond issues of taste and interpretation – involved the allocation of budgets, particularly the expensive inclusion of US artists, who were apparently invited quite late in the process. 48 The earliest documents in the museum archive that include names of North American artists are dated 17 January 1969, and it seems Beeren only made his selection after his travels in November 1968. Furthermore, although the Stedelijk Museum was a much larger and better funded institution, Beeren’s budget was significantly slimmer than Szeemann’s (thanks to the latter’s support by Philip Morris), and Szeemann arranged for many artists to travel through Amsterdam, so that they could install ‘Op Losse Schroeven’ first before heading on to Bern. 49 As images, publicity material, film footage, interviews and eyewitness accounts indicate, while some installations by US artists were constructed on site without the artists present, many of their compatriots came to install their work.

The Installations

‘Op Losse Schroeven’ opened at the Stedelijk Museum on 15 March 1969, and ran until 27 April. 65 works by 34 artists were exhibited in twelve galleries and various ancillary spaces, occupying the ground floor of the museum’s west wing, a hallway, the main staircase, entrance space and upper floor windows, as well as several locations outside the museum.

Amongst the US artists who travelled to Amsterdam to create new works for the exhibition, Lawrence Weiner set off a flare on the city limit for his work The Residue of a Flare Ignited Upon a Boundary (1969). Only a wall label in the exhibition with Weiner’s name and the title of the work indicated that this event had occurred. Richard Serra’s Splash Piece (1968/69), which he executed in hot lead against the external walls of the Stedelijk Museum with the assistance of Philip Glass and Robert Fiore, was lost from the exhibition entirely when it was vandalised soon after it was made. Heizer inserted a metal grate into the pavement in front of the museum (Wigvormige uitgraving in het trottoir voor het Stedelijk Museum, overdekt door een metalen rooster, or Wedge-shaped Excavation in the Pavement in Front of the Stedelijk Museum, Covered by a Metal Grate, 1969), which to the uninitiated might have seemed like an air vent to a metro tunnel underneath. Robert Smithson and Dennis Oppenheim also created new works for the exhibition, but went even further outside of the regular environs of the institution, although they added references (and in Smithson’s case, a portion of the work) into the exhibition space proper. For his displacement piece, Smithson placed a mirror in a heap of dirt in the Southern Dutch town of Heerlen (the so-called ‘Site’ segment of the work) and created an installation of a dirt heap with a mirror inside it in the last gallery in the exhibition parcours (the so-called ‘Non-site’ segment of the work) (Mirror Displacement, 1969). Smithson often divided his work into a ‘Site’ and a ‘Non-site’ component to emphasise the mutual referentiality of the individual part: neither component is complete without the other, which is never present, creating a never-ending circle or mise en abyme: a perpetual pointing to the larger environment and back to the gallery. Oppenheim also chose to make a work off-site, in a field in Finsterwolde near Groningen, some 200 kilometres away from Amsterdam, where, according to Carel Blotkamp, the artist ‘had the land belonging to farmer Waalkens… ploughed and sown according to certain patterns’. 50 The catalogue for ‘Op Losse Schroeven’ lists a work that would have inscribed the outline of the floor plan of galleries 1, 6, 9 and 12 of the Stedelijk Museum into a landscape in New Jersey. It is, therefore, unclear if this is the same work transposed onto a Dutch, rather than a US, landscape.

Other works outside the museum included interventions by Dutch artists made in direct response to the site. Ger van Elk used glazed bricks to add a decorative rectangular corner to a rounded pavement edge in front of the museum (Luxurious Streetcorner, 1969). Jan Dibbets dug trenches to reveal the base plinth at the four corners of the museum (Museumsokkel met 4 hoeken van 90o, or Museum Pedestal with Four Angles of 90o, 1969), an action that figuratively elevated the museum onto a pedestal and simultaneously destabilised its foundations by laying them bare. Marinus Boezem’s work was meant to interact with the most variable of elements – the weather – in creating an ever-changing and ephemeral work, which further deflated the notion of the museum as a temple of permanence. 51 He hung white bed sheets out of the first floor windows (Beddengoed uit de ramen van het Stedelijk museum te Amsterdam, or Bed Sheets from the Windows of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, 1969), to indicate the changing patterns of wind and weather, but also to mock the Dutch habit of placing the bedding in the open window of one’s house to dry – and effectively, to show others that one does not harbour secrets and keeps clean.

Ungrounded, domesticated, decorated and made temporary by the Dutch artists, the museum was also watched. Emilio Prini arrived before the exhibition officially began and pitched a number of tents in the parking lot across from the museum, from where he studied the progress of the organisation and installation. 52 This work, titled Camping (1969), placed literally and figuratively, spatially and temporally ‘before’ the exhibition, expresses perhaps most directly the ambiguous new relationship between artist and curator. Prini’s disposition was sceptical and hesitant; however, this did not mean that he aimed directly to influence the curator or the organisation from his position. His role must be understood as closer to that of an observer, and although the result of his observations remained hidden, the mere fact of his presence prompted conjecture about their effects. In a manner comparable to Long’s walks in the countryside, Prini’s camping functions as a self-sufficient expression of artistic creativity, a ‘real’ action whose result may nonetheless be an imaginary object, a private thought or a trace of the energy invested.

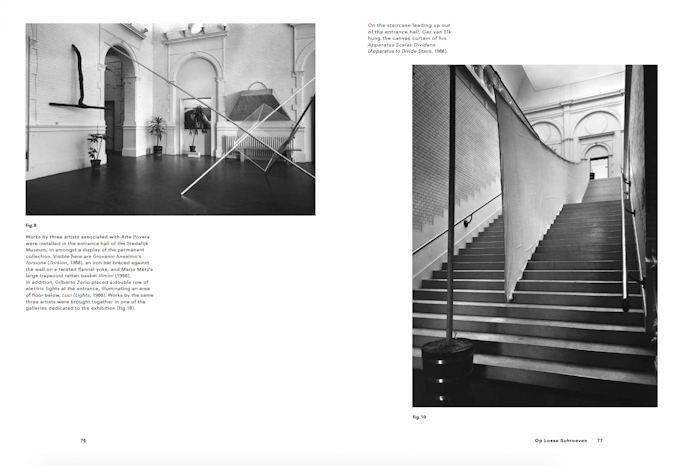

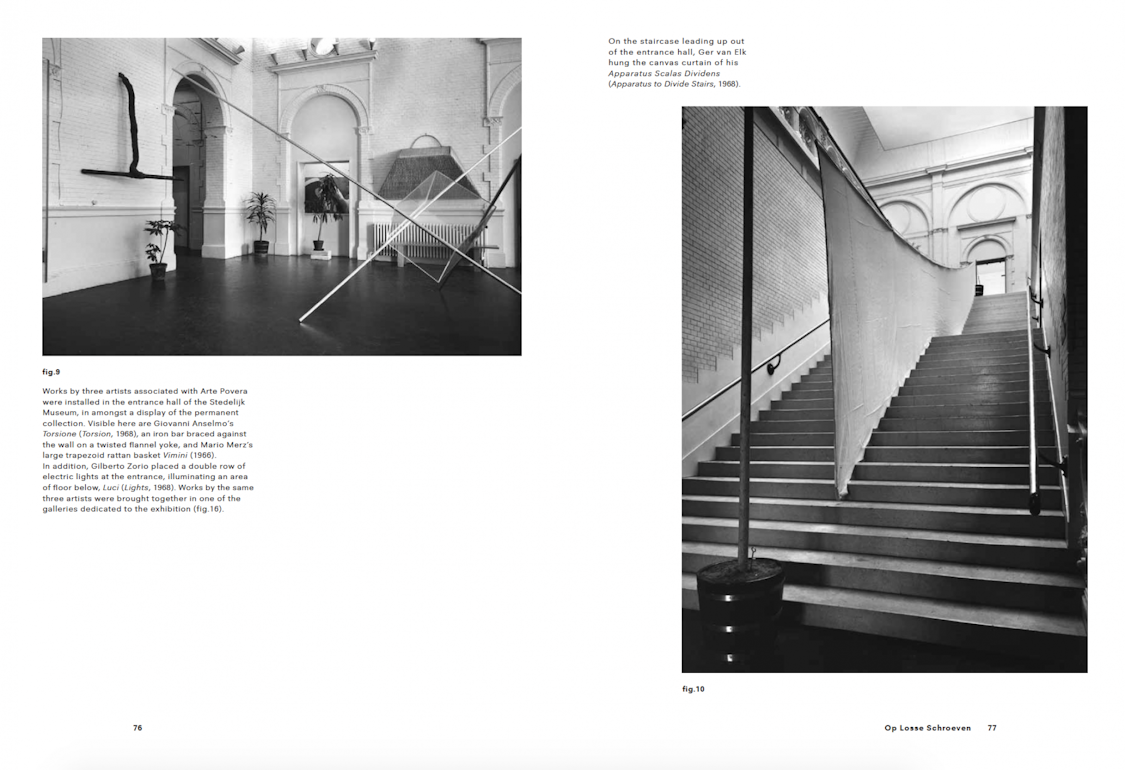

Hence, before visitors even entered the museum, several works already proposed an embellishment of the given surroundings, a critique of the institution and a substantial yet nearly invisible incision into the urban fabric. On crossing the threshold, visitors found a number of Arte Povera works installed in the entrance hall, dispersed among works from the permanent collection that would have been familiar to a returning visitor. A large trapezoid rattan basket by Mario Merz was hung on one wall (Vimini, 1966), Gilberto Zorio’s double row of electric lamps that illuminated a square area of floor (Luci, or Lights, 1968) was placed centrally in the entrance, and one of Giovanni Anselmo’s famous Torsione sculptures (Torsion, 1968), for which he tightened a piece of flannel fabric by twisting it with a metal bar and holding the tension by catching the bar against the wall, was also placed in the atrium. In the staircase leading to the galleries on the upper floor, van Elk installed the Latin-titled Apparatus Scalas Dividens (Apparatus to Divide Stairs, 1968), a canvas curtain that did exactly what the title describes and divided the stairs lengthwise. This juxtaposition of critical interventions into the architectural and institutional conditions of the museum with works by the dominant protagonists of Italian Arte Povera provided the template for the entire exhibition, and set the pace for the sequence of galleries on the ground floor.

Van Elk’s works either mockingly celebrate or directly disrupt the usual interaction of visitors with the museum. The glazed bricks of his Luxurious Street Corner may be seen as a subtle critique of the museum’s canonising authority and as a comment on the role of public art as urban adornment, while the works installed within the building suggest something more uncommunicative and dysfunctional in its social relationships. In Apparatus to Divide Stairs, the cloth curtain bisecting the main staircase meant that people moving up and down the stairs were hidden from each other, ‘so that suddenly’, in Beeren’s words, ‘you were walking past each other without knowing who was on the other side; … an unforgettable act’, while a small hanging ‘brick wall’, suspended on wires above a table in the museum’s cafeteria (Hanging Wall, 1968), made it impossible for two adults seated opposite each other to see each other’s faces. 53

Floor plans and photographic documentation of the display of ‘Op Losse Schroeven’ allow for a fairly comprehensive reconstruction of the sequence of works in the exhibition galleries. 54 Few of the images in the archive of the Stedelijk show the exhibition populated, although some do record a performance, when the installation by the Swedish artist Olle Kåks – a series of rolls of white paper mounted high under the ceiling, Process (1969) – was activated by a group of participants. Another shot depicts the mayhem of the gallery after the event. A number of images in private hands, in particular from the archives of Ad Petersen, another curator at the Stedelijk at the time, show artists during installation, but most of the photographs in the institutional archive – especially those showing works inside the galleries – appear to have been taken after the installation was complete and when the galleries were closed to visitors. They provide a record of the installation according to the generally accepted conventions of museum documentation, with little sense of interaction with the public.

The traditional architecture of the museum – with well-proportioned and ample galleries illuminated by large windows and a strictly linear layout of enfilade rooms – meant that the unfolding of the exhibition was by necessity a narrative proposition. Beeren addressed this issue by setting up an alternating choreography between galleries occupied by works of only one artist and rooms with works by several artists. He further structured the viewers’ experience with carefully calibrated density, mixing galleries only sparsely filled with more crowded rooms that follow in some cases more specifically geographic attributions or, in others, more speculative affinities. For instance, after a string of five galleries at the beginning of the exhibition almost exclusively dedicated to individual artists (Dibbets and Douglas Huebler share one room, followed by solo installations by Boezem, Paolo Icaro, Pier Paolo Calzolari and Jannis Kounellis), the first large corner gallery contained a selection of artists considered part of the Italian Arte Povera movement: Merz, Anselmo and Zorio, the same constellation of artists that Beeren had presented in the museum entrance. In the other corner gallery there was a similar grouping of work by three artists from the US: Bill Bollinger, Serra and Keith Sonnier.

A look at the different versions of the floor plan in the archive of the Stedelijk Museum suggests that Beeren’s exhibition structure of alternating densities developed late in the process. The first hand-drawn plans indicate a more incremental set-up, with a series of individual galleries of Dutch and Italian artists, focusing on Boezem and Dibbets as well as Prini, Calzolari, Kounellis (although Greek-born, he moved to Rome in the late 1950s) and Icaro, at the beginning of the exhibition, followed by the corner gallery with works by Merz, Anselmo and Zorio. Only from that point did the drawings indicate several artists sharing a space. Beeren also played with another sequence – this one geographically defined – going from European to American. On his first two sketches, two more galleries with European artists follow after the Arte Povera corner gallery, before a sequence of three rooms that contain, in various constellations, works by Walter De Maria, Robert Morris, Frank Lincoln Viner, Bruce Nauman, Serra, Sonnier, Bollinger and Alan Saret. These rooms are sometimes broadly marked on the plans with the word ‘Americans’ sketched across all three rooms. Clearly Beeren initially understood the separation between European and US artists to be compelling, even fundamental, to his exhibition concept. However, apart from the corner room devoted to Bollinger, Serra and Sonnier, which mirrored the corner gallery devoted to three Italians, his final plan mixes US and European artists, and the sense of geographical distinctness that appears to have preoccupied him in his early planning is largely absent in the final configuration.

Some installations seemed specifically placed to challenge and engage the viewer: Zorio’s Scrittura bruciata (Burnt Writing, 1968) was positioned in the middle of the doorway axis and turned in its orientation so that the viewer had to circle around to interact with it. The sculpture consists of an open, cage-like wire-mesh box and a pad of paper on which viewers were invited to scratch a message with a metal stylus before throwing their note into the box. A heated metal plate at the bottom would ignite the paper and make temporarily visible the invisible relief of the script in the process of calcination, before the paper burnt and disappeared. Other works seemed to illustrate, more or less directly, Beeren’s initial interest in new and unusual materials and their role in shaping and defining a new status of ‘objecthood’ for the artworks they construct. In the same gallery as the works by Zorio were a number of works by Merz, among them a large, ladder-shaped metal construction with a cushion of wax atop surrounded by several bushels of brushwood (Cera ferma che passa, or Still Wax Passing, 1969). Other works included two constructions made of glass and mastic, a kind of natural rubber: in Che fare? (What Is to Be Done?, 1968), Merz spelled out the title of the work in a line of mastic onto several sheets of glass leaning in one corner of the room, and in Pacchetto illuminato (Illuminated Package, 1969), he stacked sheets of glass, covered along the edges in mastic, and lit the opaque layer from behind with a single light bulb. The gallery also featured several works by Anselmo, including the now-classic work Untitled (at the time referred to as Struttura che mangia l’insalata, or Structure Eating a Salad, 1968), a small granite pedestal on the side of which a head of lettuce is held in place under a granite block, tied on with wire. As the lettuce wilts, the wire becomes less taut, making the granite block slip and fall down onto the floor.

The following gallery contained works by a number of artists, including Joseph Beuys, Marisa Merz, Panamarenko, Walter De Maria and Bruce Nauman, but, despite the range of materials and scale, the installation felt mannered and orderly, partially owing to the fragility of the works. A room with works by Nauman quickly led to the other corner gallery, in which Beeren had installed work by Serra, Sonnier and Bollinger. While impressive in their economy, scale and ambition, these three artists’ works did not appear as monumental as could have been expected, considering their often daring scale, brute materiality and frighteningly makeshift assembly. All the works were safely leaned or mounted against the walls, and only Bollinger’s Pipe (1968), consisting of two steel pipes joined by a piece of plastic tubing, jutted out into the centre of the space. But the aggressive assertiveness with which other works by these artists instil unease and physical fear in viewers does not seem to be present here. Two lead works by Serra, Right Angle Prop (1969) and Floor Pole Prop (1969), were installed adjacent to two earlier neon sculptures (Untitled and Plinths, both 1967), forming a sequence along three walls. And across the room in the opposite corner, Beeren placed two other neon sculptures (Flocked Neon, 1968 and Neon Wrapped Light, 1969) and a floor piece (Red Floor Piece, 1968), all three by Sonnier. The similarity of the approaches taken and materials used – neon, industrial pipe and tubing, fibreglass and metals – underlined the proximity of the three artists’ production. All of them worked in close contact and showed at the time with the same gallery in Cologne – Rolf Ricke’s – and had some overlap in New York (Leo Castelli) and Paris (Ileana Sonnabend).

The last three galleries of the exhibition introduced an array of artists – both Western European and North American – difficult to group together by any coherent order or theme. Those in the first of the three rooms included Minimalist painter Robert Ryman, who contributed Classico V (1968), a multi-part painting on cardboard, Carl Andre, Barry Flanagan, Alan Saret, Frank Lincoln Viner and the Swedish artist Kåks, who contributed the performative installation mentioned earlier.

The next two galleries were united by the common theme of Earth art, with works such as Smithson’s mirror displacement in dirt (the ‘Non-site’ element to the work Mirror Displacement, already described), Reiner Ruthenbeck’s Double Ash Heap (1968) and Morris’s Specification for a Piece with Combustible Materials (1969), as well as the knee-high wall built of riverbed stone by Long, which had a room to itself and concluded the exhibition parcours, leading into the museum hallway. This constellation of works created a suggestive and complex, albeit not always clear, juxtaposition of artistic practices, structured through seemingly similar sculptural forms – heaps and mounds – and materials – earth, ash, coal and so forth. Morris’s flammable materials relate to Ruthenbeck’s ash heap through a suggestion of metamorphosis, but while Ruthenbeck has a more classical concept of the poetic qualities of the materials, Morris aims at a classificatory system. Smithson’s earth mound on the other hand functions as just one element of his ‘Site’/’Non-site’ paradigm, as the record of a displacement of matter that always points beyond the confines of the museum. All works, however, were united by the deliberate casualness with which they had come to occupy the galleries, a departure from the much more formal approach of, for instance, the exhibition ‘Atelier VI’, which immediately preceded ‘Op Losse Schroeven’ and which appears as an orderly procession of paintings on the wall and sculptures on the floor, generally placed at the centre of the room and in symmetrical arrangements. 55 The expansion into unusual sites and materials was also mirrored by a concert and screening event that supplemented the exhibition. The night before ‘Op Losse Schroeven’ opened to the public, an associated programme of ‘New American Music and Film’ was presented at the Stedelijk. At 7.30 pm on Friday 14 March 1969, Philip Glass performed the organ piece Two Pages (1968), after Steve Reich’s tape recording It’s Gonna Rain (1965) was played and before a screening of Michael Snow’s film Wavelength (1966 – 67).

The final parcours of ‘Op Losse Schroeven’ gently moved the viewer from site-specific and conceptual interventions to relatively traditional sculptural works to room-sized environments and finally, in the museum hallway, to documentation of works so large in scale that they could not be represented in any other way – a testament to Beeren’s understanding of the impact of ‘situations’ as a new material for artistic creation, and to his fascination with the experiments in nature by artists such as Long, Oppenheim and Heizer. While Heizer and Long were also represented with newly created works for the museum, Oppenheim’s work was off-site far away in a field near Groningen and only documented with images and plans in a space underneath the museum staircase. As Blotkamp has argued, 56 Beeren’s expansion of the bounds and reach of the exhibition, as well as the special section in the catalogue which presented drawings and unrealised projects requested from the artists, already prefigured an exhibition that Beeren would go on to curate after ‘Op Losse Schroeven’: ‘Sonsbeek Buiten de Perken’ (‘Sonsbeek Beyond Lawn and Order’, 1971), an exhibition of artworks mainly outdoors, taking place across the entire Netherlands, often in sites as remote as barns and fields.

—

The main floor of the Kunsthalle Bern is structured into just four galleries – a large central hall and three smaller side galleries, which are accessible from the main entrance hall – with two additional galleries located on the basement level. The smaller space and the interconnecting rather than linear layout of the galleries obliged Szeemann to opt for a more concentrated spatial arrangement than that of ‘Op Losse Schroeven’.

Like Beeren, Szeemann allowed for several works to be made in situ and outdoors, making a connection into the urban fabric of the city of Bern. For fig.45 his work Bern Depression (1969), Michael Heizer hired a crane-operated wrecking ball to break open the pavement in front of the kunsthalle and create a cratered hole near the entrance, which drew the wrath and mockery of the local press. 57 Heizer mirrored his ‘depression’ in front of the kunsthalle with a long incision into the garden behind the building: a work titled Cement Slot (1969), which was simply listed as ‘Incision’ in the exhibition catalogue and consisted of a long, narrow concrete furrow incised into the lawn. Dibbets repeated his excavation of the corners of the institution (Museumsokkel met 4 hoeken van 90o, or Museum Pedestal with Four Angles of 90o, 1969) and Ger van Elk replaced a piece of pavement in front of the kunsthalle with a life-size photographic reproduction, which he inserted into the original photographed space (Replacement Piece, 1969). Robert Barry released a radioisotope from the roof of the kunsthalle building (Uranyl Nitrate (UO2 (NO3 ) 2 ), 1966–69) and Joseph Kosuth participated with a series of four advertisements taken out in three local newspapers, in which he printed his conceptual statement I. Space (Art as Idea as Idea) (1968). 58 In the exhibition catalogue, a photograph of the newspapers in which the piece was published is accompanied by a statement by the artist:

My current work, which consists of categories from the Thesaurus, deals with the multiple aspects of an idea of something. I changed the form of presentation from the mounted Photostat, to the purchasing of spaces in newspapers and periodicals (with one ‘work’ sometimes taking up as many as five or six spaces in that many publications – depending on how many divisions exist in that category). This way the immateriality of the work is stressed and any possible connections to painting are severed. The new work is not connected with a previous object – it’s accessible to as many people as are interested, it’s non-decorative – having nothing to do with architecture; it can be brought into the home or museum, but wasn’t made with either in mind; it can be dealt with by being torn out of its publication and inserted into a notebook or stapled to the wall – or not torn out at all – but any such decision is unrelated to the art. My role as an artist ends with the work’s publication. 59

Richard Long contributed to the exhibition with A Walking Tour in the Berner Oberland (1969), which consisted of the titular walk through the Swiss region (made from 19 to 22 March) and a simple poster giving the duration and title of the piece that was shown in the galleries. Robert Smithson placed a mirror into a site in the city, which was then photographed and the image shown inside the kunsthalle (Bern Earth – Mirror Displacement, 1969), and, in what might be one of the most discreet interventions into the city, Stephen Kaltenbach rubber-stamped an image of his Lips (1968) around Bern.

Two events officially unrelated to the show, but that were planned to coincide with it, have since become part of the history of ‘When Attitudes Become Form’. One was an action by French artist Daniel Buren, who Szeemann visited during the preparations for the exhibition but who did not take part and instead decided to work independently: he wallpapered his signature vertical stripes, in a white-and-pink colour scheme, over several advertisement posters and billboards in the vicinity of the kunsthalle, for which he was fined by the local authorities, who had his interventions removed shortly thereafter. 60 The other event occurred briefly after the opening of the exhibition, and might be understood as a spontaneous outburst inspired by the radical expressions of experimentation of its artworks: two Swiss citizens, writer Peter Saam and artist Hans-Peter Jost, burnt their army uniforms near the public fountain on the plaza in front of the kunsthalle, protesting against compulsory military service. Harry Shunk, the New York-based photographer who had travelled to Bern to document the installation of the exhibition and its opening proceedings (and whose pictures provide the bulk of the visual archive from which all scholarship on the subject draws) photographed this happening. As such it has been absorbed into the narrative of the exhibition, largely because photographs of the incident appear on Shunk’s contact sheets together with images of works by exhibiting artists.

Franz Meyer, the éminence grise of the Swiss museum world, 61 published an ‘eye-witness report’ on the exhibition in 1996 and this was the first attempt at a detailed reconstruction. He testifies to the exceptional response that Szeemann’s show triggered in him: ‘The “Attitudes” exhibition, unlike the contextual thematic group shows before, overwhelmed me. It was an event with a palpable inner necessity, an uncertainty maybe that was felt beneath the skin, but one that was also immensely pleasurable and inspiring.’ 62 He noted the crammed immediacy of Szeemann’s installation, inspiring unconventional, almost accidental dialogues: ‘everything was physically close and the viewer encountered it as a (highly productive) jumble, high on the wall or very low, protruding into space from the wall or independently situated in the middle of the room’. 63

Images of the exhibition, especially those taken during the installation period, vividly convey the sense of a densely packed and somewhat jarring installation, with every wall, corner and floor surface utilised to make room for art. However, it would be naïve to imagine that Szeemann did not conceive of a basic structure for his exhibition. As a curator, he was very aware of spatial choreography, and clearly knew where to place the showstoppers, as an early entry in his exhibition diary, right after a studio visit with Richard Serra, reveals: ‘From Cologne, I will get the large Belt Piece as a key work for the exhibition.’ 64 And accordingly, upon entry to the kunsthalle, a visitor would have been faced frontally with the spectacular nine-part rubber and neon belt piece from 1967, a lead Splash Piece (1968/69) executed on site by Serra and three Prop Pieces (Shovel Plate Prop, Close Pin Prop and Sign Board Prop, all 1969), placed to the right of the entrance to the hall. Greeted by such a bold statement, visitors then had to decide which way to turn. To the left, a passage opened onto a single gallery; to the right, there were the main three rooms; and at the left rear corner of the entry hall a small staircase led to the lower level and its two galleries. Each of these paths through the exhibition was defined by different sensibilities and concerns.

The lower galleries were dedicated to an investigation into the energetic, material-driven practices of several Italian artists commonly categorised with the terms Arte Povera and Primary Energy, including Giovanni Anselmo, Alighiero e Boetti, Mario Merz and Gilberto Zorio – even though the inclusion of related works by artists such as the Turkish-born Sarkis and, from the US, Neil Jenney broke the national monopoly. The North galleries, to the left of the entrance hall, were predominantly dedicated to more spare, even immaterial installations, which followed decidedly conceptual and performative principles. These included works by US artists Andre, Ryman, Fred Sandback, Mel Bochner and Sol LeWitt, as well as the Germans Hanne Darboven and Franz Erhard Walther.

Turning right from the main entry hall, the two smaller and linked South galleries, which give access to the large and much higher central hall, provided a prelude and context for the densely installed selection of artists to be encountered in the main space: the first of them contained works by artists of a previous generation that can be claimed as influential predecessors, such as Beuys, Claes Oldenburg and Ed Kienholz, but also had works by Long and Flanagan. Beuys and Oldenburg were especially important for Szeemann as perceived influences on the younger generation of artists, both in their organic, process-driven way of working and their early experimentation with common materials unusually employed as artistic media, such as felt, fat and sulphur in the case of Beuys, and papier mâché, rubber and cloth in the case of Oldenburg. Szeemann particularly considered the different uses and roles of the same materials by artists of different generations and geographic regions, as demonstrated by his interest in the way in which both Beuys and Morris were using felt as a sculptural material. By 1968 comparison between the different sculptures made of felt – and speculations about the artists’ mutual influences regarding the use of this material – had become commonplace. 65 To make this comparison direct, Szeemann placed a felt stack by Beuys (Fond, 1969) and several of his Fettecke (lard placed into the corner and edges of a room, 1969) in the first gallery, and Morris’s wall work Felt Piece Number 4 (1968) in the following room. Oldenburg was represented by two sculptures (Street Head II, 1960 and Pants Pocket with Pocket Objects, 1963) that referenced earlier works such as The Street (1960) and The Store (1961), and by two soft sculptures that could be described as representations of common objects rendered in soft materials (Soft Washstand, 1965, and Model (Ghost) Medicine Cabinet, 1966). Morris himself had acknowledged the influence of Oldenburg on his most recent sculptural practices using non-rigid materials. 66

Connecting the two South galleries was Barry Flanagan’s Two Space Rope Sculpture (1967), eighteen metres of heavy commercial shipping rope that gently meandered from the middle of one gallery to the next. In the same room as Morris’s Felt Piece, Szeemann placed four works by Bruce Nauman that measured the artist’s body (including Neon Templates of the Left Half of My Body Taken at Ten Inch Intervals, 1966) in close proximity to two works by Mario Merz, Sit-in (1968) and Appoggiati (Leaning, 1969). A self-portrait of sorts by fellow Italian artist Alighiero e Boetti – a silhouetted figure on the floor made of 110 hand-size cement balls, titled Io che prendo il sole a Torino il 24 febbraio 1969 (Me Sunbathing in Turin on 24 February 1969, 1969) – was placed in the centre of the room, apparently added by Boetti after the rest of the room was installed. Beuys and Oldenburg, Morris and Nauman, Merz and Boetti; Szeemann set up in these rooms a rapid sequence of alternating influences and examples of current practice that respectively prefigured and introduced some of the sculptural strategies of the time, including the use of soft materials, neon, mastic and other uncommon media, the body of the artist as a formative component, as well as stacking, piling, random order and chance as compositional strategies.

The parcours culminated in a grand gallery dedicated significantly, if not exclusively, to the youngest generation of artists from the US, such as Bill Bollinger, Gary Kuehn, Walter De Maria, Alan Saret, Keith Sonnier and Richard Tuttle. Despite being interspersed with works by German artist Reiner Ruthenbeck and Swiss artist Markus Raetz, the North Americans clearly dominated the installation of this central gallery. Many of the works in this room were produced on site, as a short film made by Marlène Bélilos for the Franco–Swiss Télévision Suisse Romande documents. 67 The film shows Sonnier applying fibre particles onto enormous sheets of cloth, tacked to the wall or pulled away from it with strings. Flocked Wall and Flock Pulled from Wall with String (both 1968) are perhaps the most directly visible examples of a creative process shaping the form of a work. The same film also shows Weiner on the staircase leading to the lower galleries producing A 36” x 36” Removal to the Lathing or Support Wall of Plaster or Wallboard from a Wall (1968), a square area of wall from which he removed the surface layer of plaster. As Weiner conveys in the documentary, the work existed already in its verbal description: its execution is not important and could be done by anyone; the idea for the work is what counts.

In the downstairs galleries, installations by Paris-based Turkish artist Sarkis using electricity and water, now known as Rouleau en attente (avec néon blanc) or A Roll Waiting (with White Neon) and Conversation (both from 1968), works by Italians Anselmo, Merz, Zorio and by the North American Jenney can all be broadly grouped in a category of natural materials and processes of transformation. Water and fire, dissolution and incineration, the changing of aggregate conditions and the definition of light – even neon and fluorescent light – as a ‘natural’ material, all come to bear on the art presented on the lower level of the kunsthalle. If the central hall had a strong emphasis on US post-Minimalist practices, downstairs Szeemann surveyed a different sensibility. In these rooms the transformation of materials, although still tied to the creative process in the studio or conceived through an experimental relation to the original object, was also understood to be symbolic or at least metaphorical, and the works were never solely understood as physical manifestations of the inherent qualities of the materials.

Across the street from the kunsthalle, in a space normally used as a school, the exhibition continued with several large-scale installations and some scattered works that seemed not to fit elsewhere. These included Robert Morris’s Specification for a Piece with Combustible Materials (1969, an instruction piece that, as mentioned earlier, was also included in ‘Op Losse Schroeven’), Michael Buthe’s Untitled (1968), a painting-object made of torn-canvas strips on stretchers, Allen Ruppersberg’s Untitled Travel Piece, Part 1 (1969), consisting of a card table covered in white tablecloth displaying four regional newspapers from the United States (Desert News from Salt Lake City, Utah, Omaha World Herald from Omaha, Nebraska, Chicago Tribune from Chicago, Illinois, and The Plain Dealer from Cleveland, Ohio), as well as the work Confluenze (Confluence, 1967) by Pino Pascali, a large field of square shallow metal containers filled with blue-dyed water. According to Meyer’s eye-witness report, works by Thomas Bang, Marinus Boezem, Pier Paolo Calzolari, Paul Cotton, Ger van Elk, Rafael Ferrer, Emilio Prini, Frank Lincoln Viner and William T. Wiley were also displayed at the school.

Looking back on ‘When Attitudes Become Form’ and ‘Op Losse Schroeven’ from a distance of over twenty years, Szeemann asked himself ‘why did Bern succeed?’ and concluded: ‘Amsterdam was conceived more museum-like and nearly each artist had an individual room. In Bern, by contrast, the climate of departure of a new art after 1968 was palpable.’ 68 Evoking what has become the classic image of ‘When Attitudes Become Form’, Szeemann characterises the crowded installation in Bern as a direct expression of a climate of revolt, experimentation and freedom, a narrative with which ‘Op Losse Schroeven’ has not been able to compete. The Amsterdam exhibition has likewise paled in the historical record given the energy and excitement attributed to the installation process in Bern. Even though for ‘Op Losse Schroeven’ a significant number of artists came to install their works on site – and several site-specific, new and public installations were made – the same activity for ‘When Attitudes Become Form’ has, following Szeemann’s lead, been particularly accentuated. Szeemann’s diary entries for the final week of installation of ‘When Attitudes Become Form’ reveal an almost constant coming and going of artists and their assistants, families and friends, as well as gallerists. Heizer and Serra, Anselmo, Merz, Zorio, Boetti and Kounellis, Beuys and Buthe, Ruthenbeck, van Elk, Dibbets and Boezem, Long, Flanagan, Louw and Lohaus, Weiner, Kosuth, Artschwager, Kuehn, Jacquet and Sarkis all arrived in the final days of preparation to install their works – both new and old – in Bern. Moreover, testaments to the intensity of the installation period were, as already described, given corroborating visual form; not only in Shunk’s installation photographs but also in Bélilos’s film. Szeemann would seem to loom large behind these documentary endeavours: he invited Bélilos to film the artists working in the galleries and Shunk’s photographs became a part of his personal archive, rather than remaining at the kunsthalle.

Sources of Influence

Despite the spatial limitations imposed by the strictly linear progression of galleries at the Stedelijk Museum, Beeren, like Szeemann, dreamt of a new approach to exhibition installation – less formal, less museum-like. He directly drew inspiration from a model of display he had observed when travelling to Turin in the final week of 1968. Following a recommendation by Piero Gilardi, Beeren visited the short-lived but influential Deposito D’Arte Presente (DDP), a mix of studio, gallery and storage space (hence, deposito). 69 Located at 3 Via San Fermo, in a 450-square-metre space previously used as a car showroom, the DDP, active between June 1968 and April 1969, was founded by collector and local philanthropist Marcello Levi, who modelled it on the private art associations of the turn of the century. Teaming up with art critic Luigi Carluccio and gallerist Gian Enzo Sperone, Levi worked closely with artists associated with Arte Povera, including Anselmo, Calzolari, Gilardi, Merz, Pistoletto and Zorio. Gilardi helped renovate the space and remained involved over its ten-month run. In a 1995 interview, Beeren recalled his impression of the DDP:

As for the artists, Gilardi was so clearly against the gallery establishment, so I had the idea that all artists thought the same way. This was confirmed when I arrived in Turin, like a bureaucrat, really, with the museum floor plan offering each of them a room. They weren’t the least bit interested. They had their Deposito. That gave them a way of both storing and exhibiting their work; it was a generously sized stockroom where the best works, works that are so well-known today, all stood next to each other. 70

The DDP, as Beeren clearly understood, presented not only a different sort of installation than that of a conventional museum show – it was an outgrowth of a new kind of art. (‘The status of the work of art had changed’,he later reflected.) 71 He also acknowledged the more active role the artists played in the placement and organisation of the display: ‘The extraordinary thing about “Op Losse Schroeven” was the process. Up until then all you did was place something or hang something, but this time the operation was carried out by the artists together with the curator.’72 Beeren was inspired by the presentation of the DDP, given its lack of formality and with works less isolated than in a conventional museum exhibition. He liked the collaborative organisation and haphazard character of the installation, and responded to the dense placement of all manner of objects, hung on the wall, leaning against each other or placed in close proximity to each other on the floor, seemingly without an overarching curatorial logic.