Matter Minding, or What the Work Wants: Aldo Tambellini’s Intermedia

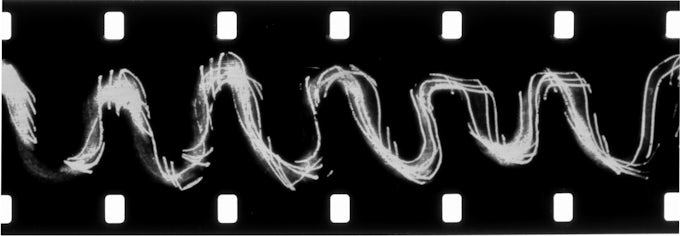

Hanna B. Hölling looks at the relationships between blackness, mediality and intermediality, as well as at materiality and physicality and claims that the work ‘teleport[s] us into a realm in which black wanders between media, and perform an aesthetic of change’.