My Parents, Their Children

There are two distinct figures in the painting, but there could be many more. There are two figures, a pale-skinned man and a dark-skinned woman, but there could be less than two, because their bodies dissolve into a deep-red background, onto the field of which black intrudes from the edges. The woman holds out two hands, in a shrug or a supplication or a gesture of persuasion, and the man holds out one hand. His left hand is nowhere. In the place where a left hand might go, if he had one, there is a white blur, like a tornado in a movie or chalk scrawled sideways on a surface. His right hand might be gesturing or giving up; it might have just let something fall to the impossible floor.

In the painting My Parents, Their Children (1986) by Lubaina Himid, the Black woman’s hands are more definite than the white man’s single hand, and her expression is more definite too, containing: one, sorrow; two, suspicion; three, fear of harm; four, concern; five, strength of will; six, inscrutable sense of self held away in private trust, just in case. Are these two ‘my parents’ or ‘their children’? If they are the parents or the children, then the other – the parents or the children – might be the roughly, barely painted column of white that blocks the space in between them, at the base of which the proposition is reversed in neat lowercase letters: ‘their children/my parents’. At the top of the column, suspended in its cloudy black head, these words appear: ‘my grandfather never met my grandmother’.

In photographs of strangers, the kind you still find in overflowing boxes in vintage stores or just by browsing social media, sometimes the relationships feel instantly comprehensible – mother and father holding their child’s hands, one each, the adults pressing close – while in others you don’t know who anyone is. I want to think of the cloudy and careless entity made of white and black paint that separates the two figures as their unexpected child, the kind of thing that happens when two irreconcilable differences meet and have sex. But the words ‘my grandfather’ and ‘my grandmother’ hover above their heads like labels. These two are the grandparents. The title’s declaration – ‘My Parents, Their Children’ – refers to the parents who are not depicted, or are depicted as this slur of white and black paint in the middle, which I cannot get over; nor can the two figures, because it separates them. In families that contain different histories of race, which is to say different histories of failure, courage, pride and humiliation, which is just to say ‘histories’, the simple facts – this person met this person, this person was born – take on strange dimensions. The acid bath of history can break up a body into parts, were it not that the body goes on insisting on its weird integrity, just by being factually present, just by the world emanating outwards from and falling into it as it does from and into all bodies.

Between a white woman and a Black man there might be the idea of sex, or the fear or promise of it, as these two characters in the commedia dell’arte of race relations have been tasked so many times with performing a pantomime of white fear of the body – the Black stranger and the trembling white wife, and so on. Against this background they can represent either the triumph of a liberal progression towards a mythic post-racial world or the exciting, awful danger of falling into animal nature, depending on where you look from. They play pantomime because their encounter is symbolically always mediated by a white man. This dance excludes Black women, as if excluding a difficult truth.

Between a Black woman and a white man – turned into a canvas, into symbols – there has been a more terrible proximity, and therefore there is no available pantomime. The figures hold their three hands out as if unsure of finding any other gesture, or any gesture at all. To a great extent, the problem of blackness as a question of category (authenticity, quantity, personal brand) rather than of experience has been determined by the ultra-productive sexual violence that white men have inflicted on Black women, formalised as partus sequitur ventrem: the mandate that slave status pass through the mother, the law that authorized the breeding of slaves. Had the grandparents met, family bonds might have mediated and domesticated this connection founded on property rights, on commodification and on extreme and permissible violence; but instead they float separately in a scab-red space.

But history is both gentler and worse than my telling of it. Grandpa and Grandma have both come beautifully dressed for the occasion of their first meeting, him in a suit and her in what looks like blue velvet. His shirt is buttoned all the way up and her hair is slicked down and neatly parted. Their faces show no hope, but their clothes look hopeful, like best clothes picked out for a party. If their expressions are not the most welcoming, if they face us instead of each other, that is only to be expected from two people who have lived in the same world in different worlds. Their eventual encounter happened belatedly, in the body of the artist, who gives them a frame in which to stand almost together.

A grandmother and a grandmother are someone’s children and someone’s parents, in the endlessly recursive nature of a family tree, until it stops with someone who tasks herself with telling this endless recursion and gets lost and found in it, or goes on differently.

Away (Flat)

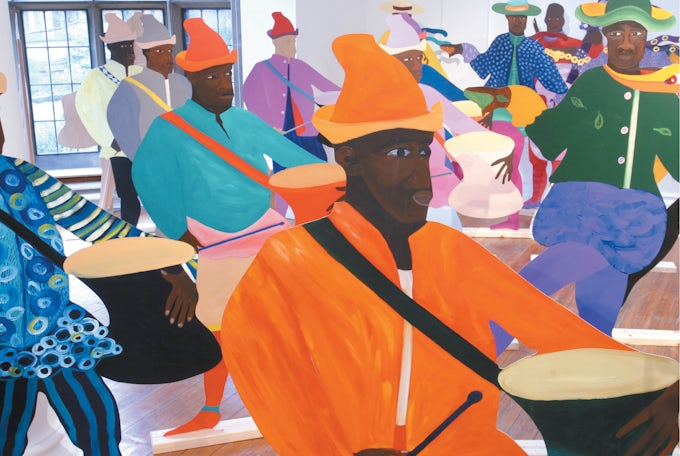

Himid’s installation Naming the Money (2004) comprises speaking depictions of Black servants and slaves that hover between sculpture and painting. The money is named by the sculptures’ flatness, their many-ness, and Himid refers to them as ‘life-size cut-outs’ – an absence the size of a life. The Black people represented in the cut-outs are lifted from portraits of wealthy white people and reimagined. In a sense they are set free from the frame and in a sense (so flat!) they remain tied to it, because they originate there, or this origin is the justification for their renewed presence in the gallery. In the original paintings they symbolise white wealth, which is to say they symbolise their own absence from home. In Himid’s work, they symbolise themselves. ‘I used to live with my family; now my family lives apart’, says one, or Himid has one say. With voices and names, they fall down from the high ceiling of something called history and onto the wooden floor of ordinary pain. The walls get the most attention, but a museum needs depth too, needs a ceiling and a floor.

All together, in a room at the Harris Museum and Art Gallery in Preston in 2007, the figures performed the necessarily clumsy procedure of introducing a new theory of history. Also in 2007, at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the sculptures of Naming the Money appeared next to whitemarble ladies reclining.01 There, their flatness became more like that of a knife, aimed uselessly at stone-cold, self-satisfied flesh. This kind of knife, the cutting edge of figuration’s white flatness, often has to stay private and imaginary.

Of another work, Swallow Hard (2007), paintings of Black people on British ceramics, Himid says, ‘The point I am often exploring vis-à-vis the Black experience is that of being so visible and different in the white Western everyday yet so very invisible and disregarded in the cultural, political or economic record or history.’02 The ceramics themselves, the museum itself, should make Black people visible, because the museum and the ceramics were minted by the invention of blackness. But money is flat and disappears when turned on its side.

These are old problems. They circle around and go nowhere. The Black diasporic condition that Himid sees as characteristic is the loss of the dimension of time – perhaps this zero temporality fuels the cyclical nature of the art world’s discovery, forgetting and rediscovery of Black artists.

At the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London in 1985, Himid’s exhibition ‘The Thin Black Line’ claimed and critiqued the art museum through the inclusion of a group of Black and Asian artists, all women. The transition from the first significant entries of Black women artists into European art spaces to the white declaration of the post-racial is so fast it makes your head spin. Thirty years after ‘The Thin Black Line’, a similarly curated show would feel no less striking and fresh, which is as much a testament to the lie of the post-racial as it is to Himid’s genius. The relentless othering of non-white artists requires constructing each individual as, paradoxically, either an extraordinary exception or a good example. Himid has resisted this tokenization by bringing her context into the gallery with her; by curating shows with other women of colour; by archiving, celebrating and showing their work. We have to go on doing this interesting and useful work for each other because we have a lot to say to each other. Representation is only reductive to the extent that its possibilities are reduced.

The publication created to accompany ‘The Thin Black Line’ refers to all the artists as Black, while a 2011 book published by Tate on this show (and two others) refers to ‘Black and Asian women artists’.03 In the decades since the exhibition, the meaning of British blackness has changed and also stayed the same – surveilled and marginalised. The conflation of Black and Asian diasporas into a unified Black identity, common in Britain up until recently, reflected their shared postcolonial status in the country.

Since then blackness and brownness have become pretexts for modes of policing, aimed at either ‘gangs’ (sociality) or ‘terrorists’ (alienation) but with many overlaps. Most importantly, the prominence of US struggles in global Black politics has problematized political blackness to the point of no return, usefully redirecting attention towards the conditions in the colony rather than those at the colonial centre. As a result, it is impossible to make an equivalence between the political subjectivities of the colonised people whom the coloniser encounters in their homeland, amid their own historical forms and antagonisms, and of Black people removed forcibly from Africa and brought to unfamiliar islands as raw labour. The task of collapsing the struggles of all racialised peoples into a single category has now moved to the phrase ‘people of colour’, a term crafted by Black women as a collective indicator of solidarity across different experiences of race. This term is now itself under erasure, as indicated by increasingly popular phrases such as ‘non-Black people of colour’ and ubiquitous critiques of ‘poc solidarity’. These are not mere intellectual or curatorial niceties: questions of what constitutes blackness and of the singularity of Black experience cannot be fully closed while anti-blackness persists – nor is it ethical to leave them entirely open.

Himid’s work, her being, travels through different racial regimes separated in space and time, navigating by pattern: What is the same and what is different? Who is like me and who is unlike me? These questions cannot be resolved because they are tools for navigating the world and the self. These artworks cannot be resolved: Himid talks often in interviews about continually revising old paintings so that they stay alive. Sometimes, in works like Swallow Hard, Himid condenses the question of a Black diaspora to its most simple expression – a reminder that Black people exist, have existed, will exist. This is still very hard for people to understand. ‘We must leave evidence that we were here, that we existed… Evidence of who we were, who we thought we were, who we never should have been’, says the disability rights activist and writer Mia Mingus, of the oppressed in general.04 The evidence is as much for ourselves as anyone else. For all the efforts of the modernists to keep the great ceiling of history intact, it falls down as dust, very slowly, over generations. Let’s try to believe in this, and not be afraid.

Away (Ocean)

The ocean passages that obliterated time and family, all of that, that fragmented the world and joined it together, are braided through the incoherence of water. Everything we say about the void falls off into it. Now I’m looking at a floral-patterned plate with a black face on it (from Swallow Hard) and thinking of the ban on images of Auschwitz with which Adorno thought to bring the trash of memory/forgetting into the court of critique. As a way of leaping over the question of a ban on images, Himid’s work is informed by the communicative possibilities of pattern – that play of abstract image and concrete life. Lives fall into patterns, too. That’s what it means, to be living out a history, to be living out of history, to be living out of a suitcase that you like to refer to as history.

In Himid’s series Guardian Paperworks: Negative Positives (2007–ongoing), images of Black people in The Guardian newspaper are framed by serenely patterned overpainting, lifting a part of the image up and out – a hand, an arrow – and repeating it until the epidermalised punctum of the celebrity skin is soothed away. An object’s self-representation, which is a technological and not psychological matter, falls outside a ban on representation. For the European museum, Black art begins as a representation of absolute alterity, and everything else it strives to do (become ordinary, for example, like a plate) has to start from there.

The perversity of Europe is that only atop a pile of corpses, symbolic and real, can a person become banal. The Black artist in Europe is condemned to always be interesting. What is interesting about the idea of a Black artist in Europe is the idea of someone carrying around a terrible hurt and exonerating everyone of this terrible hurt by doing so. The Black artist in Europe is condemned to always have been a curiosity. What is curious about the idea of a Black artist in Europe is the idea of someone carrying around a terrible hurt and insisting that we all look at it. There are two answers: forget yourself, or forget them. But you go on revising the answer because you are not sure if the question was right.

What caused this hurt? Asked in an interview about her paintings of the sea and water, Himid says: ‘The fear of and obsession with the sea used to exactly mirror my life at the time of painting these works in which I could not navigate my way out of the dangerous places because they seemed safe. The strategy for escape seemed more frightening than the known danger.’05 From Fred Moten’s poem ‘there is religious tattooing’: ‘it’s simple / to stay furled where you can’t live’.06 I think he means it’s not simple, but that the apparent simplicity of staying furled, contained within yourself, is an attempt to ignore the sea – ‘furled’ is a verb for a sail that currently doesn’t know anything.

For all its mastery, all its serenity, Himid says her series Plan B (1999–2000) was made ‘at a time in my life when I was frightened a lot of the time’.07 In Plan B, two adjacent painted views of the same thing – sometimes a thing transformed, sometimes just transposed – make a drama of the flat self-identity of mute objects. A popular antianxiety technique advises writing down your name and the date and place, then itemising what you can see in your surroundings (chair, screen, blanket, glass jar of oil, boots, phone…). The reality of objects is supposed to give contour and relief to the shapelessness of fear, but this technique feels lonely. It would be better to go inside the anxiety, inside the sea, than be confronted with the brute banality of oneself as an object amongst objects, picked up and put back down again wherever. But perhaps there is a process of becoming-thing, in art or life, that only then makes it possible to confront the fear of which the sea has become the object.

In her 2016 book In the Wake, Christina Sharpe refers to the afterlife of slavery as materialised in blackness, as producing a condition of ‘non/being’, alongside Black resistance to this foundational non/condition.08 If Black culture is deployed all over the world as solace and excitement, sprinkled into the museum to keep things edgy and real or worthy and wholesome, it is not despite the positioning of blackness as the external edge of the human – as where the human blurs together with the commodity – but because of it. For Sharpe, living this impossible position of non/being requires something called ‘wake work’, a phrase implying alertness, mourning and the trail that a ship leaves on the water through which it passes.

Thinking of the ways people carry long-held hurt and neglect with them into their adult lives, the child psychologist D.W. Winnicot wrote: ‘I can now state my main contention, and it turns out to be very simple. I contend that clinical fear of breakdown is the fear of a breakdown that has already been experienced.’09 I suspect that Winnicot wasn’t thinking of Black women, but here we are. The frightening possibility of escape-as-loss that the ocean once seemed to present is the reality that the loss, the escape, the great sea change already happened a long time ago, before the lines of experience were organised into something like an identity, when loss had no past or future.

Out of fear we make images of safety, and out of images of safety we make a world. Himid’s painting Between the Two My Heart Is Balanced (1991) stages a meeting between two serene Black women on a frightening sea. The work is a Tate holding, bought with sugar money fattened into banality over generations. Two women sit on a boat, the wake trailing out behind them. A block of stripes between them is a stack of maps or something more energetic. Maps are no longer needed. The painting from which the title is borrowed, by a white man, depicts a white man sandwiched between two women, his mother and his wife. Just kidding – it’s just two women. In Himid’s version there are no white women, no white men. She says of the two women: ‘The women take revenge; their revenge is that they are still here they are still artists, that their creativity is still political and committed to change, to change for the good.’10 The original is revised to include its missing heart. Revision is a nice word because it implies we’ll see each other differently; or one day see each other again.

Footnotes

-

Naming the Money was included in the exhibition ‘Uncomfortable Truths: The Shadow of Slave Trading on Contemporary Art’.

-

Lubaina Himid in conversation with Jane Beckett, ‘Diasporic Unwrappings’, in Marsha Meskimmon and Dorothy C. Rowe (ed.), Women, The Arts and Globalization: Eccentric Experience, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013, p.194.

-

See Thin Black Line(s): Tate Britain 2011/12 (exh. cat.), Newcastle upon Tyne: University of Central Lancashire, 2011.

-

Mia Mingus, ‘About’, Leaving Evidence, available at https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/about-2/ (last accessed on 13 December 2016).

-

L. Himid in conversation with J. Beckett, ‘Diasporic Unwrappings’, op. cit., p.215.

-

Fred Moten ‘there is religious tattooing’, Hughson’s Tavern, Southport: Leon Works, 2008.

-

L. Himid in conversation with J. Beckett, ‘Diasporic Unwrappings’, op. cit., p.215.

-

See Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016.

-

D.W. Winnicot, ‘Fear of Breakdown’, in Donald Woods Winnicott, Clare Winnicott, Ray Shepherd, and Madeleine Davis (ed.), Psycho-analytic Explorations, Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1989, p.90.

-

L. Himid, quoted in Maud Sulter, ‘Without tides, no maps’, in Revenge: A Masque in Five Tableaux (exh. cat.), Rochdale Art Gallery, 1992, p.32.