As the art world rushes back to pre-pandemic hectic pace, Afterall Writer in Residence Anahita Delcorde takes the time to look back at Maria Eichhorn’s gesture of closure and refusal for her solo show at Chisenhale Gallery in 2016. In the first part of this long form essay, Delcorde ponders over what a time-giving and generating practice might look like in the face of contemporary capitalism’s ever-advancing occupation of any interstice of our lives.

A few months ago, in April, like most of Paris, I tested positive for Covid-19. Experiencing fatigue like I had never felt before, the thought of having to work seven days later, after the end of my quarantine period, became a daunting prospect. As it sometimes felt like a magnet was weighing me down and keeping me glued to my bed, Covid revealed itself to be quite the checkup. Unable to feel completely guilt-free for not being productive, for not working, I was flooded by a constant flux of to-do-lists that hazily, but surely, rooted itself in my foggy mind. Alienation at its finest. Even though I didn’t know how, I needed things to slow down, space to rest, sleep. For The Right to Be Lazy , to quote Paul Lafargue’s eponymous text, 01 for the freedom to be absent, for one’s need to do nothing. A need that felt illegitimate, as the whole art world was rushing in planes with the start of biennales, international fairs, documenta, and projects swarming everywhere. Past talks in the microcosm of the art world about changes in ways of travelling, working, or consuming following the health crisis, had never felt more distant.

During this period, and in the rare moments of clarity, I was able to take some time to dig into numerous notebooks in which over the years, I scribbled ideas, kept press releases of shows and copied extracts of texts that had sparked curiosity. Notebooks that I hadn’t had the time to properly explore in ages and that, strangely enough, mostly revolved around ideas of ‘post-work’, 02 withdrawal, silence, and artistic absence. In the pile of notes, Maria Eichhorn’s closed exhibition at Chisenhale Gallery, 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours (2016), felt as topical and urgent as ever.

Honouring the spirit of Maria Eichhorn’s project, the following paragraphs are an ode to all my lost material. They are a nod to forgotten writings, unexplored ideas and essays I returned to, as well as a way of taking time to think about an ‘absent’ work.

A genuine emptiness, a pure silence is not feasible – either conceptually or in fact. If only because the artwork exists in a world furnished with many other things, the artist who creates silence or emptiness must produce something dialectical: a full void, an enriching emptiness, a resonating or eloquent silence. Silence remains, inescapably, a form of speech (in many instances, of complaint or indictment) and an element in a dialogue. 03

In her essay ‘The Aesthetics of Silence’, Susan Sontag explores the hidden meaning of what appears to be ‘absence’: an absence of words, speech, or space. For Sontag, art which takes its ground in a lack, in an absence, paradoxically points out to what is not there.By doing so, it renders visible what is invisible, and focuses our attention on what is not allowed to be seen or heard. Total absence, as such, is not possible. 04

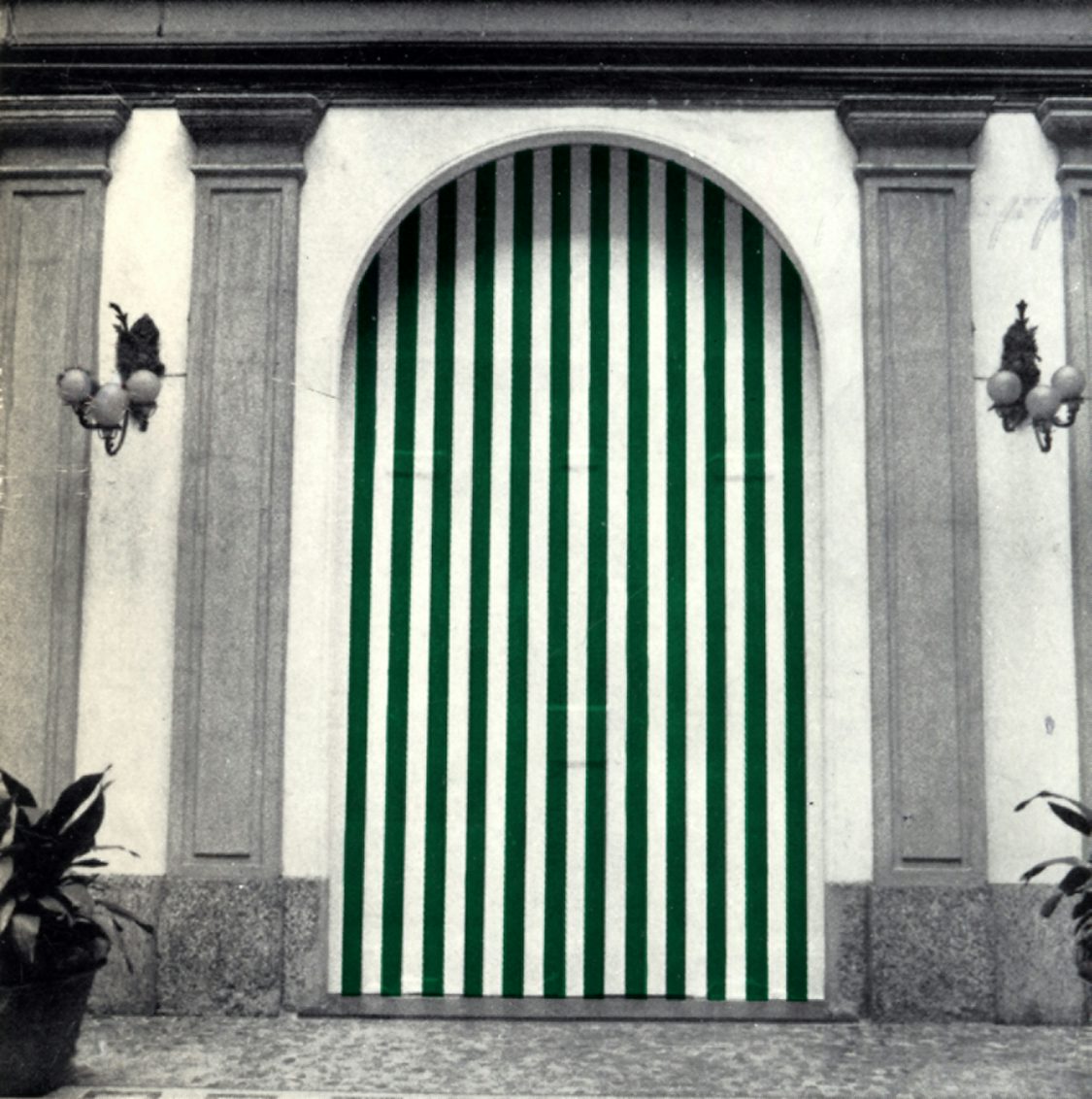

Susan Sontag’s words resonate when thinking about the radical gestures of concealment and closure operated by conceptual artists in the 1960s and 1970s. For his first solo-show organised by the Apollinaire Gallery in Milan in October 1968, the French artist Daniel Buren sealed the entrance to the gallery with his signature white and green striped wallpaper. The stripes were reminiscent of a health and hygiene service ban, as if marking the building as unsafe. The gallery was made inaccessible and was left empty. Artworks, normally contained in a space dedicated to their exhibition, were absent. The work appeared to be located elsewhere. In December 1969, the American artist Robert Barry declared that his solo exhibition at the Art & Project Gallery in Amsterdam would be closed. The shutdown was announced through a note on the gallery’s locked door and through invitations reproducing the same message. 05 The art space, out of function, seemed to have lost its role and efficacy, since it exhibited what appeared to be ‘nothing’.

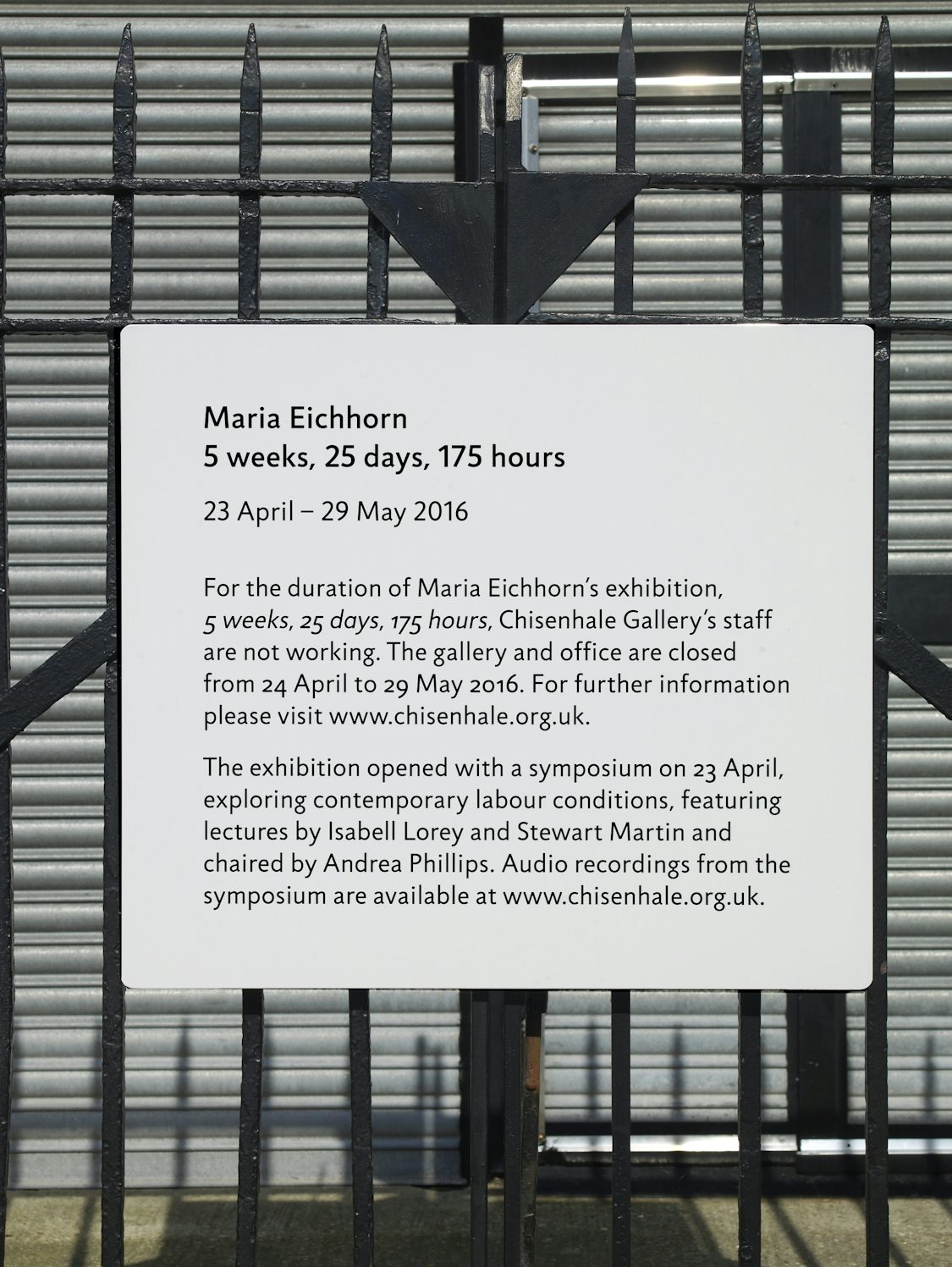

Roughly fifty years after Buren’s and Barry’s works, German artist Maria Eichhorn had the Chisenhale Gallery in London closed for her exhibition 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours, from 23 April to 29 May 2016. Eichhorn requested that the gallery staff continue to receive pay, but not be allowed to work during the time of the exhibition. The staff did not need to explain what their plans were during the duration of the show. The gallery space was as a consequence left empty, and the fences prohibited anybody from getting in, its closure being signalled with a note on its gate explaining the artist’s intervention. The idea behind 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours emerged after Eichhorn had conducted workshops and interviews with the gallery staff in July 2015, as part of their commission for the gallery’s How to work together programme. Eichhorn asked the fifteen salaried employees what their tasks consisted of, what they enjoyed and did not enjoy in their work. A year later, the exhibition began with a symposium (on 23 April 2016) tackling the issues of art labour with special interventions by writers and academics such as Isabell Lorey and Stewart Martin. The symposium ended with a discussion with the audience, leading to the closure of the gallery.

The apparent absence of artworks and the obstruction of the exhibition space prompted several issues regarding the relationship between the artist, the visitor, and the gallery, and pointed out the dynamics existing between time, labour and space. 06 The issue surrounding what appears to be an artistic withdrawal is compounded by contemporary concerns with audience participation. Eichhorn’s closed Chisenhale show can, through this prism, be read as an exclusionary gesture. What happens when the artist forces an exclusion?

During the symposium, Eichhorn explained that she was interested in the ‘fundamental possibility of suspending the capitalist logic of exchange by giving time and making a life without wage labour imaginable’. 07The closed exhibition is a powerful image of the ‘waging of producing nothing’, 08 to quote the then director of Chisenhale Gallery, Polly Staple. Consequently, does Eichhorn’s own artistic labour equate to ‘doing nothing’? Is paying the gallery staff while the gallery is closed, an act of financing laziness?

Angry non-visitors and shut-off exhibitions

When Maria Eichhorn’s 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours ‘opened’ in London, the exhibition caused quite an uproar. Responses in popular news outlets such as Time Out ranged from there was ‘not much going on at all’ to ‘PLEASE don’t ask if this is art’, or deemed that the artist ‘wasn’t really exhibiting’. 09 Eichhorn herself recalled that the first reaction to her proposal at the Chisenhale Gallery had been an ‘hearty laughter’. 10 Several other mainstream news articles condemned Eichhorn’s work as forbidding people from entering the gallery and experiencing art, and found that the show was an inexplicable vacation for which London taxpayers should be outraged. The work generated debate in regard to several matters: what exactly is art in the show, and why is the audience not allowed to access it.

Feelings of anger and discontent are quite familiar to Maria Eichhorn’s practice. For her 2001 exhibition at the Kunsthalle Bern, Eichhorn decided to dedicate the budget of her solo show to much needed renovations of the art centre, leaving the galleries empty for its duration. Intended to dismantle and deconstruct the power structures at play in an art venue (financial, material, artistic, political) and the system which enables an exhibition space to function, the gesture was accompanied by a catalogue thoroughly exposing the institution’s financial decisions and its precarious state. As Eichhorn explained,

Some people were angry when they went into the Kunsthalle because they didn’t know it was going to be empty most of the time. They expected to have something to look at, and they wanted their money back because they had paid to see something. The only thing I didn’t like was that they shouted at the staff… it was both good and bad for the Kunsthalle, because they almost didn’t have any visitors during the show and the fact that the building was in such a bad condition was made public. I talked to people from the city and they didn’t want it to be exposed on such a level. 11

Even though these two works seem to be quite opposites (one closing the space, the other keeping it open), they both rely on the emptiness of the art venue. The articles about the Chisenhale Gallery exhibition in the popular press reveal that this emptiness was interpreted as ‘deprivation’, a denial of service by the gallery. This fact triggered feelings of anger, as if Eichhorn was taking away something from the public (this ‘something’ understood as art), and dispossessing them of a building that was theirs, as the Chisenhale Gallery is a non-for-profit, part publicly funded, contemporary art centre. 12

The outrage triggered by Eichhorn’s piece is revelatory of the ways in which art is consumed. If the news articles viewed the exhibition as ‘forbidding people from looking at the art’, it is because art is still understood and better accepted as an object-based practice, which can thus be commodified. To quote the artist herself, ‘a work of art is seen in terms of its ability to accumulate monetary value and its reproductive form: when a work is purchased – when it becomes property – it can reproduce capital. As soon as it is acquired, all effort is focused on increasing its value.’ 13The reactions to Eichhorn’s work are thus deeply rooted in a capitalist vision of art as a commodity, which Eichhorn, through her gesture, is trying to subvert. Responding to Exhibition and Events Curator Katie Guggenheim’s question about the nature of the artwork, the artist replied that the art is situated in

the empty gallery and the sign on the gate outside explaining the reason for the closure, the symposium and the conversations that develop around the work, and the free time given to the Chisenhale staff… The exhibition consists of the staff members not working: that I give the employees time, and that they accept the time. 14

As such, Maria Eichhorn’s work is located in her asking the staff to withdraw their labour, consequently leading to the closure of the gallery. Eichhorn here plays with artistic authorship: as there is no artwork without the staff and without taking into account the specific context of the Chisenhale gallery. The artwork also has an ‘expiration’ date: it will end once the exhibition ends, and thus when the gallery staff re-enters the gallery. Eichhorn’s own labour is then deeply dependent on other actors: the artwork can only become such if and only if, the staff agrees to stop working. As the work cannot be bought, Eichhorn’s action seems to function as a direct stance against the commodification of art as accelerated under late capitalism. The artwork seems to escape the establishment of monetary value on the work, its exchange and circulation. To quote art historian Elizabeth Ferrell,

Eichhorn impertinently asks the question ‘how can a collector possess an idea?’ to illuminate the effects of late capitalism on art production today: ‘when a work is freed from the idea of ownership in both material and non-material respects, it can neither be possessed nor sold; the mechanisms of circulation have no way to exploit it; have no effect. How is such a work created?’ 15

Eichhorn’s work at the Chisenhale Gallery can thus be understood as a response to the previous question. Mechanisms of circulation are thwarted. 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours is an exploration into conditions for making an artwork unmarketable, upsetting the neo-liberal understanding of art as solely commodity.

Give me transparency

Closing the art centre problematises and interrogates the structures of the institution, its conditions for the exhibition of art. Eichhorn’s action helps to unveil an opacity surrounding the art institution. By asking the staff to withdraw their labour, the artist focuses the audience’s attention on this same labour: how exactly is it organised? What are the profiles of the people who work at Chisenhale Gallery? How is the institution run and managed? All of these issues, usually invisible, are here exposed by the artist through a publication produced with the Chisenhale staff, and the symposium organised on the first day of 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours. It is revealed that most of the staff come from an art school, and are artists, even though they don’t have time for their own practice. The salaries of the gallery staff are only partially covered by public funding, forcing them to spend most of their time securing other sources of funding in order to cover both production costs (since the Gallery exhibits commissioned work) and salaries. As such, the then director of the Gallery, Polly Staple, spent 75% of her work fundraising. 16 The Chisenhale Gallery is thus highly dependent on funding from individual benefactors, and vulnerable to the Arts Council’s cuts. As Staple stated,

There is a broader conversation here about the state of the public sector in the UK. Within a neoliberal context, entrepreneurial activity is regarded as a strength. At institutions like Chisenhale we become our own worst enemy. We show that we can raise money, through individual giving or editions for example, we show that we can be less dependent on public funding, and as less of that money is available it is seen as less necessary to us. Although it is. It’s self-perpetuating, because we’re all trying to survive and do good work at a level that attracts individuals to support. 17

The lack of public funding has forced longer hours of work, unstable job offerings and a de-waging of tasks. Because ‘it is imagined as speculation with oneself in a secure future of abundant cultural capital’, 18 art workers accept precarious positions, with no secure wage.

Eichhorn’s work as such, is not so much an exclusion of the audience per se, or an artist’s strike, but rather shifts the demand to suspend the work on the level of the art institution itself. We are forced to look at the gallery, its structure, and the precarity of certain aspects of the art sector. To quote Maria Eichhorn,

The Chisenhale staff have every reason to strike… due to the lacking support of the public authorities. This is how art is privatised and disappears into the arsenals of the sponsors and the rich. The tax money paid by the community flows instead into areas that the majority of citizens don’t want to support: armaments, wars, nuclear energy. The rich receive tax benefits, while the budget for social expenditures is cut more and more. 19

In a way, the artwork is directly integrated (or one can even say re-placed) into the public realm. The art is not ‘shut off’ in a specific, dedicated space; but on the contrary, the art gallery is to be understood and deciphered withincurrent social and economic relations and power dynamics. The work exists as an idea in the public sphere, generating discourse, rather than objects. It could paradoxically be called participatory, as the artwork is only achieved once the staff agrees to participate in its project. The focus on the institution as such also displaces the work from within the art centre to its understanding as an event in the world. In Artificial Hells, art historian Claire Bishop describes participatory art as intending to place pressure on ‘conventional modes of artistic production and consumption’, and where the ‘artist is conceived less as an individual producer of discrete objects than as a collaborator and producer of situations’. 20 Eichhorn offers here an understanding of participation as necessary transparency and reintegration into broader social dynamics. As Bishop claims, ‘we need to recognize art as a form of experimental activity overlapping with the world’. 21

Against productivity

Eichhorn’s resistance to capitalism does not limit itself to the nature and form of the artwork. Its parameters and ‘subject-matter’ are deeply rooted in a criticism of the art market, its generated capital, and more specifically neo-liberalism’s temporal organisation of life. The outrage following Eichhorn’s exhibition is not only linked to the obstruction of the space: it’s also a reaction to the fact that Eichhorn was enabling fifteen people not to work for five weeks, while continuing to be paid.

Following Jonathan Crary’s analysis in 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, the ultimate tactic of resistance to neoliberal power structures lies in doing nothing, understood as not producing anything (which, Crary links to the act of sleeping). 22 Neoliberalism is to be understood as the rise of a 24/7 life rhythm of constant control and productivity: sleep is seen as detrimental because it is a time not invested in direct productivity. As he explains, ‘sleep poses the idea of a human need and interval of time that cannot be colonized and harnessed to a massive engine of profitability, and thus remains an incongruous anomaly and site of crisis in the global present’. 23 ‘Downtime’ is increasingly reduced to the verge of disappearing because it does not generate financial value: ‘time for human rest and regeneration is now simply too expensive to be structurally possible within contemporary capitalism’. 24 As such, resting might be considered, in current neoliberal conditions, as one of the most controversial acts of living. Resting is not an efficient time (in financial terms), since nothing of value is produced for an external owner. There is a profound incompatibility of anything resembling reverie with the priorities of ‘efficiency, functionality and speed’. 25

By implementing free time, Eichhorn is, in a way, enabling the staff to rest and regenerate; or at least, to have the choice to do so. During the duration of the exhibition all work emails were automatically deleted so not to burden the staff once they re-accessed the gallery. Crucially, Eichhorn did not ask the staff to notify her about what they were doing or planning to do during the gallery’s five-week closure. They were free to choose and decide how to spend their time. In so doing, Eichhorn put forward a new understanding of labour, as consisting of absolutely no production. The value inculcated into the space itself plays an important role in resisting the production of capital. Indeed, as the artist explained, ‘in a certain way the building should also calm down, and have time off, not work. These spaces should also not be used or made available in other ways: not rented for profit or otherwise capitalized’. 26 Eichhorn instates time, a time that suspends, a time outside exploitation. Interestingly, the German word for ‘to suspend’, aussetzen, means also ‘to expose’ and ‘to strike’.

The interviews conducted by Eichhorn also circle back to the issue of time as experienced by the fifteen salaried employees of the gallery. They lament the lack of time to focus on research and the conceptual thinking behind exhibitions and events, as their working hours are hijacked by never-ending admin. Katie Guggenheim recalls this situation: ‘I do like the chaos to a degree but not when I feel like I can’t do my job well because there isn’t enough time…. I don’t get the time to digest, think and follow through, and I don’t get time to research things thoroughly’. 27 As art jobs are increasingly defined by the constant necessity to do more administrative work, working hours extend. All the while staff face a de-waging of labour due to the dwindling public funding their admin tasks are often geared to secure. In reaction to this situation, Eichhorn also broadens the definition of work as it is attached to wage labour, and questions the basis on which wage is established, in particular in the arts. Shouldn’t work be a time for reflection too? How can one be productive, if faced with administrative tasks taking over time for creativity and research? Shouldn’t work consist, at times, of actually not producing anything?

With 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours, Eichhorn interrogates the assignment of value to time and work particularly in the arts sector, where creativity is very poorly (if at all) remunerated yet it’s expected. To quote Marina Vishmidt, creativity has been ‘internalized as a workplace norm’, 28expected yet with no proper time dedicated to fostering it. Faced with precarious positions and sinking wages, work has become excessive while, at times, being negated as work. According to Lorey,

More and more, new service-based production takes place without wage or social security. The creative, communicative and affective capacities of workers, which tend to be formed outside of paid employment settings, get appropriated in companies and institutions as work that is usually unpaid. 29

In the arts sector, this aspect is reinforced by the disengagement of public funding forcing the staff to represent their institution, while conducting ‘private’ activities, in order to attract new benefactors. At exhibition openings, parties, through social media, art workers are expected to embody the institution. Work emails require staff to be rapidly and constantly available; gallery openings become sites for scoping potential investors. As Polly Staple explains, ‘when you go to an opening and you’re still representing the gallery, you can’t clock out and say, “I’m just going to chat”. You’re always conscious of the fact that you’re working’. Deputy Director Laura Parker adds, ‘What’s quite different about working in an arts organization is that it becomes difficult to separate your job from your life’. 30 Working relationships with artists are also private ones and extend beyond the gallery. Boundaries between private and professional are more and more porous: art workers have to constantly interact and engage, for professional matters, even in a time when they are not being paid.

This 24/7-work rhythm of life is created by a permeability and lack of distinction between times of work and leisure. Private relations and working relations interlock; social relationships are made productive. 31 Maurizio Lazzarato famously qualified this as ‘immaterial labour’, a form of labour which involves the subjectivity of the worker, their personality and social relations which add to ‘the production of value’ while being oppressed by ‘organization and command’. 32 This aspect of late capitalism has also been identified by Gilles Deleuze in his ‘Postscript on the Societies of Control’. Deleuze argues that the rooting of neoliberalism has led to a shift in society’s structures: we are no longer in disciplinary societies, as expressed by Michel Foucault, but in what Deleuze qualifies as ‘societies of control’. The institutional regulation of individual and professional life proceeds in ways that are continuous and unbounded. Gaps, times of doing nothing are disappearing: means of control are multiplied and invested in all areas of life, notably through technological advancements (emails following the staff everywhere, maintaining the idea that people have to be constantly present), in order for individuals to be endlessly productive, profitable. Permanent availability is expected. As Deleuze states, ‘in the societies of control, one is never finished with anything’.

For Crary, ‘one of the forms of disempowerment within 24/7 environments is the incapacitation of daydream or of any mode of absent-minded introspection that would otherwise occur in intervals of slow or vacant time. Now one of the attractions of current systems and products is their operating speed’. Eichhorn’s gallery show was intended to re-empower the staff in disposing of their time, and ‘opened’ the space for slow, vacant time. The title of the show itself reinstates a necessary division of time between work and leisure. Twenty-five days does not correspond to the number of days in five weeks, but to the working days affected by the exhibition. 175 hours correspond to the time of wage labour: the time in which the staff is supposed to be at the Chisenhale offices and are paid to do so. Re-establishing the distinction between work time and leisure is an implicit act of resistance against the neoliberal tendency of erasing boundaries between private and professional life and of redistributing time away from neoliberalism’s demand of constant presence, effectiveness and attention.

Footnotes

-

Paul Lafargue, The Right to Be Lazy (trans. Alex Andriesse), New York: NYRB Classics, 2022

-

Andy Beckett, ‘Post-work: the radical idea of a world without jobs’, The Guardian, 19 January 2018, available at https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/jan/19/post-work-the-radical-idea-of-a-world-without-jobs (last accessed on 26 October 2022).

-

Susan Sontag, ‘The Aesthetics of Silence’, in Styles of Radical Will, New York: Picador, iBook, 2013, p.21.

-

Ibid. , pp. 24–25.

-

Lucy Lippard, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972,Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997, p.133.

-

Following Danielle Child’s analysis in Working Aesthetics: Labour, Art and Capitalism, labour is here to be understood as remunerated time of work. See D. Child, Working Aesthetics, London: Bloomsbury (e-book version), 2019, p.3.

-

Katie Guggenheim, ‘Maria Eichhorn in Conversation with Katie Guggenheim’, in Mathieu Copeland and Balthazar Lovay (ed.), The Anti-Museum: An Anthology, Fribourg and London: Fri Art and Koenig Books, 2017, p.133.

-

Polly Staple, ‘Preface’, in P. Staple (ed.), Maria Eichhorn 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours, London: Chisenhale Gallery, 2016, p.4, available at https://chisenhale.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Maria-Eichhorn_5-weeks-25-days-175-hours_Chisenhale-Gallery_2016.pdf (last accessed on 26 October 2022).

-

See Matt Breen, ‘A Gallery in East London has just opened an exhibition that’s permanently closed’, Time Out London, 3 May 2016, available at https://www.timeout.com/london/blog/a-gallery-in-east-london-has-just-opened-an-exhibition-thats-permanently-closed-050316 (last accessed on 26 October 2022).

-

Himali Singh Soin and Maria Eichhorn, ‘Maria Eichhorn talks about her solo exhibition at the Chisenhale Gallery’, Artforum [online], 14 April 2016, available at https://www.artforum.com/interviews/maria-eichhorn-talks-about-her-solo-exhibition-at-chisenhale-gallery-59479 (last accessed on 28 April 2022).

-

Mai-Thu Perret, ‘Institutional Exposure, Interview with Maria Eichhorn’, in M. Copeland (ed.), Voids . A Retrospective, Zurich, Geneva and Paris: JRP|Editions, Ecart and Éditions du Centre Pompidou and Centre Pompidou-Metz, 2009, pp.149–50.

-

As the director of the Chisenhale Gallery at the time Polly Staple stated in the exhibition publication, ‘as a publicly funded gallery we have a responsibility to audiences. 27% of our funding is public money, so there is a degree of accountability in everything we do. I think about the range of people we are engaging with, as well as the range of work that we’re presenting in the program, and the values of the organisation as a whole.’ The Chisenhale Gallery heavily relies on funding from public organisations such as the Arts Council England. Applications for these types of funding put forward ‘participatory engagement agendas that publicly funded organizations in the UK are encouraged to embrace’. Grants ask for art projects to be ‘accessible’, and to take into consideration a wide audience. P. Staple, Maria Eichhorn, 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours, op. cit., p.33.

-

Maria Eichhorn, ‘Maria Eichhorn Public Limited Company (2002)’, in Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson (ed.), Institutional Critique: An Anthology of Artists’ Writings,Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009, p.389.

-

K. Guggenheim, ‘Maria Eichhorn in Conversation with Katie Guggenheim’, op. cit., p.137.

-

Elizabeth Ferrell, ‘The Lack of Interest in Maria Eichhorn’s work’, in Alexander Alberro and Sabeth Buchmann (ed.), Art After Conceptual Art, Cambridge, MA and Vienna: MIT Press and Generali Foundation, 2006, p.210.

-

P. Staple, ed., Maria Eichhorn, 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours, op. cit., p.31.

-

Ibid., p.36.

-

Isabell Lorey, ‘Precarisation, indebtedness, giving time: Interlacing lines across Maria Eichhorn’s 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours’, in P. Staple, ed., Maria Eichhorn, 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours, op. cit., p.39.

-

K. Guggenheim, ‘Maria Eichhorn in Conversation with Katie Guggenheim’, op. cit., p.136.

-

Ibid., p.284.

-

Jonathan Crary, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, London: Verso, 2013, p.87.

-

Ibid., p.10.

-

Ibid., p.14.

-

Ibid., p.88.

-

K. Guggenheim, ‘Maria Eichhorn in Conversation with Katie Guggenheim’, op. cit., p.138.

-

Ibid., p.30.

-

Marina Vishmidt, ‘Mimesis of the Hardened and Alienated: Social Practice as Business Model’, e-flux journal, March 2013, p.8.

-

I. Lorey, ‘Precarisation, indebtedness, giving time: Interlacing lines across Maria Eichhorn’s 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours’, op. cit. , p.40.

-

P. Staple ed., Maria Eichhorn, 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours, op. cit., p.33.

-

Maurizio Lazzarato, ‘Immaterial Labour’ in Friederike Sigler (ed.), Work. Documents of contemporary art, London: Whitechapel Gallery, MIT Press, 2017 (1996), p.30.

-

Gilles Deleuze, ‘Postscript on the Societies of Control’, October, vol.59, Winter, 1992, p.5.

-

J. Crary, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, op. cit., p.88.