José Bedia was born in 1959 in Havana and is now based in Miami. He graduated from the Instituto Superior de Arte, Havana, in 1981. His installations, which frequently incorporate drawn or painted elements, are informed by religious beliefs and practices in Afro-Cuban and Native American traditions. He had a solo show at the Castillo de la Fuerza as part of the 1989 Bienal de La Habana.

José Bedia: I was part of the Bienal from the beginning, from 1984, and not just as an artist. I worked in the restoration department at the Museo [Nacional de Bellas Artes] and was therefore part of the installation team: unpacking, stretching, framing and hanging works, then packing them up afterwards to send them back to the artists. In 1989 they gave me the chance to have a solo exhibition because I won the prize for my work in the previous Bienal. In 1986 I participated with just one installation and this won an award. The work is now in the collection of the Museo.

Lucy Steeds: Tell me about this work for the second Bienal.

JB: It was related to my experience with the Native American people in South Dakota, in particular the Lakota Sioux people. Jimmie Durham found a way to introduce me to them and to send me there. Jimmie’s a great guy. I didn’t have the money at that time so he gathered it from friends: Claes Oldenburg and his wife [Coosje van Bruggen] provided the money for me and another Cuban artist, Ricardo Brey.

LS: And this was when you, Brey and Flavio Garciandía were artists in residence at the State University of New York, at the invitation of Luis Camnitzer?

JB: Yes, that was in 1985. The work I made in 1989, for the third Bienal, was completely different. That came from my research into Afro-Cuban traditions and from my experience in Africa. By then I was just back from Angola, from my time there in the Cuban army. Before then my link with Africa was through the Palo Monte tradition – I’d been initiated into this branch of Congolese religion in Cuba.

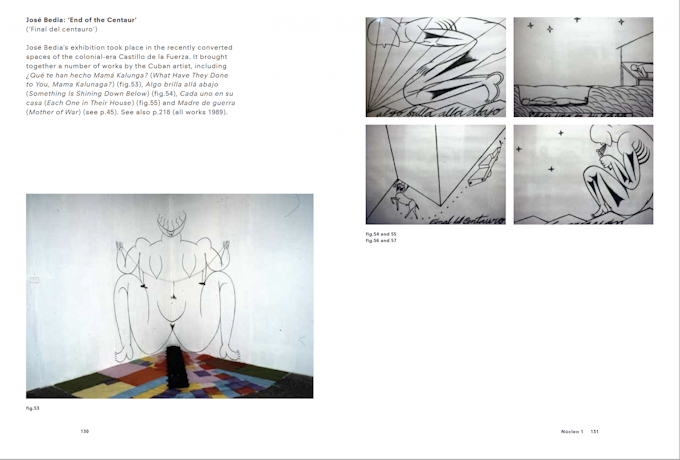

LS: How did you come up with the title ‘Final del centauro’ [‘End of the Centaur’] for your exhibition in the third Bienal?

JB: Of course a centaur is a mythological beast. For me the title was a metaphor for the end of the mythical era. In Cuba at the time everyone thought I was talking about the end of Fidel Castro because he’s associated with the horse – he’s nicknamed ‘the horse’, ‘El Caballo’ – and centaurs are half horses. My friends thought I was crazy and would get into trouble. But it was more to do with an idea about the end of the mythological: I was pointing towards our living in a rational, mechanical, industrial society. The title was a warning. I was concerned about the permanent loss of traditions – all around me, in many places across the world.

LS: Your exhibition had a direct connection then with the theme of the Bienal, ‘Tradition and Contemporaneity’. This was also the focus of the conference discussions, did you take part in those?

JB: I don’t remember there being a theme of ‘Tradition and Contemporaneity’. And I didn’t participate in the panels in the auditorium. I met many friends through the Bienal and had many discussions, but not in a formal context.

LS: Was there an ongoing conversation between one edition of the Bienal and the next?

JB: I was really involved in the Bienal until 1989, but in 1990 I left Cuba. For me the intention of the Bienal was really good, but in reality, in a sense, it was betrayed. They said they wanted to give a chance to people of the Third World to appraise themselves because they never had the opportunity to show in the big biennials of São Paulo or Venice. And, as everybody said, that was a wonderful idea. But in the end, they were waiting for Julian Schnabel or Joseph Kosuth to arrive and they ran around after those guys, and for me that was a betrayal. If you really want to do something in relation to the Third World, how can you put so much emphasis on these people? And it was the same with the film festival in Havana: people from Paraguay, Cameroon, Bolivia and Burundi were invited, but it was the arrival of Robert De Niro, Robert Redford and Francis Ford Coppola that mattered. For me, it’s ridiculous – a joke. I have always been infuriated by this betrayal of official intentions in Cuba. They say one thing and yet they move in another direction.

LS: Did you include social commentary on the Cuban situation in ‘End of the Centaur’?

JB: I touched on certain things about the society. In particular I included a drawing referencing living Congolese traditions in Cuba. This showed a large tree with many people crouching and kneeling behind it, and the title was Tanto gajo y no da sombra [Under the Big Tree Nothing Grows, 1989]. People immediately interpreted this as relating to the situation in Cuba, seeing it as a reflection on the dictatorship.

LS: Was there political critique, for instance in the work Juguete para niño africano [Toy for an African Child, 1989]?

JB: That was my silent revenge against my presence in Angola. I’m an artist but I was sent in there as a soldier, which I didn’t want. The work you mention drew on a kind of tradition created by Cuban soldiers: on a particular day of the year, each produced a toy, made by hand, for an Angolan child – a small gesture. The toys were generally related to war: tiny Kalashnikov machine guns, grenades, little tanks and planes – made with tin cans, wood or plastic caps. Among all these military toys, I finally saw one that was different: it had two ducks sitting on top of wheels. For me this provoked a fantasy in which the anonymous Cuban solider who made this piece was respecting the African tradition of the Bantu areas, in which ancestry is represented as a couple – a couple of animals or a couple of human beings. For me these two ducks reflected the local culture and tried to project that idea positively into the future. And the toy worked as a metaphor, by putting the live traditions of Africa on wheels, moving them forwards. This was a giant toy for the future of Angola, and for the future of Africa. My intention was to talk about the situation in Africa, to make a work about my presence in Angola, but subtly, indirectly in relation to the war. It was my own healing process, doing that installation. Maybe the only nice thing to come out of fifteen years of Cuban intervention in the Angolan war was the idea that a soldier might make a toy and give it to a child. I never knew who made that toy, I just found it and asked the chief if I could keep it. He consulted another chief, and then another chief, and they said I could take it away.

LS: In a review of the third Bienal de La Habana, Camnitzer compares and contrasts it with another show that year, ‘Magiciens de la Terre’, which took place in Paris. 01 You were also involved in this other exhibition – did you show related work?

JB: There were similarities and differences between my contributions. I engaged with the issue of Afro-Cuban traditions in both ‘Magiciens de la Terre’ and ‘End of the Centaur’. And in both I worked between what is three- dimensional and what is completely flat. ‘Magiciens’ was amazing. To be there in that moment was the best training. Meeting people from many parts of the world making work like me – that was a marvellous thing. The curators mixed us all up, treating us all with the same respect, dissolving boundaries.

LS: The only other artist who was, like you, in both the Havana and Paris exhibitions of 1989 was the Nigerian painter Twins Seven Seven.

JB: I know he was in ‘Magiciens’ but I never met him because there were two locations for the exhibition and I was mostly in one, at [the Grande Halle de] la Villette, while he was in the other, at the [Centre Georges] Pompidou. Meeting artists from around the world was one of the great things about that show. I would take a break from installing and talk to people. I established friendships with Joe Ben Junior, the Australian Aborigines, Richard Long, Cyprien Tokoudagba from Benin, Esther Mahlangu from South Africa…

LS: Did the curatorial work in Havana feel like more of a team effort? Did you find ‘Magiciens’ a more authored, perhaps less organic, exhibition?

JB: There were individuals working for the Bienal: Gerardo Mosquera was involved and Nelson Herrera Ysla, for example. The exhibitions had two different styles. What I remember of the Bienal is a mess, a craziness, a madness – but in the end everything came together. In ‘Magiciens’ they had more capacity: they were able to do more and to do things more easily. There was money to bring all those people together and produce those giant installations. The production of that show was amazing. I hadn’t thought about comparing the global reach of both ‘Magiciens’ and the Havana Bienal before but I think it’s interesting. Given the emphasis on national representation, the Venice Biennale is different, a little bit tricky. And São Paulo was completely like Venice.

LS: Did your experience of ‘Magiciens’ speed your departure from Cuba?

JB: At that time I don’t think I anticipated living outside Cuba. It was a particular moment, because as Cuban artists we didn’t sell anything. We supported ourselves with parallel jobs, working as teachers, designers or, as in my case, restorers. But we had a public that expected something from us – a bunch of followers who really admired what we did – not only me but all the artists at that time. That was from 1981 to 1989 or 1990, it was less than ten years. Then my whole generation left. We felt stuck. I was 32 years old, I had no studio and a family to feed. I could see no quality of life and no opportunity to develop my profession, so I left. I tried to survive in Mexico for a while but eventually I came here to the US, like everyone else. Now I hear from friends who still live in Cuba, or from new artists there, whom I’ve met since, that conditions are different, that there is a chance to get recognition and travel outside, to go back and forth. People live as artists, by selling their work. In my time you had to go to the Minister of Culture in order to get permission to leave, and it was almost impossible – going from one official to the next – and you had no money, so you had to get the ticket from them too. It’s ironic but always a previous generation has to make sacrifices in order for it to be easier for the next. After leaving Cuba people looked at me differently. I lost a lot of contacts. And of course I made new friends. Unfortunately, no matter how close we are in Miami to Cuba we don’t have any cultural links.

LS: Tell me about your involvement in the Bienal since 1989.

JB: They gave me another solo exhibition in 1991 and by then I was living in Mexico. I showed in the Casa de África, a museum in Old Havana, in connection with the ethnographic collection there. But on the fifth day they took my work down. It was censorship, although they didn’t say they didn’t like what I was doing, they just gave a ridiculous excuse: that they wanted to paint the building. During the latest Bienal, in 2009, they included me in a group exhibition with two Cuban masters, Wifredo Lam and Raúl Martínez. It was about how three artists used the influence of avant-garde art from around the world in order to talk about the local reality. It was a nice idea. But I didn’t go. They brought in five of my paintings from my dealer in Mexico.

LS: Is it important to you to be celebrated in Cuba as a Cuban artist?

JB: Artists now are pushing to be international. For me this is a little bit tricky – I don’t think that’s necessarily the right way to go. People tell me I’m international but I’m not completely satisfied with that. I am a Cuban artist, wherever I go, no matter where I live. Even when I’m not accepted as Cuban in Havana because I left the country. I am still concerned with what is going on in Cuba. It’s very different now from in the 1980s: today people don’t want to be tied to an identity, they find it old-fashioned, primitive or folkloric. I’m not afraid of that: I live my identity, I live my culture.

Footnotes

-

See Luis Camnitzer, ‘The Third Biennial of Havana’, Third Text , vol.4, no.10, Spring 1990, p.81, and reproduced in this volume, p.207.