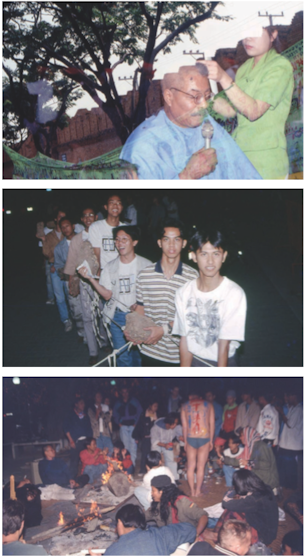

Our story begins with a photograph that Mit Jai Inn, one of the organisers of the Chiang Mai Social Installation (CMSI), shared with me. The image shows a line of people receding diagonally into the dark. It is night, and the mood seems festive and buoyant. Smiles are etched onto faces that are consciously posing for the camera. Many of the figures are carrying a piece of rock, and a rope seems to bind them to each other. Fleshing out the story behind the photograph, Jai Inn told me:

I organised a participatory walkabout around Chiang Mai on the last day of the Week of Cooperative Suffering in 1995, which took place from midnight until six in the morning. Everyone who joined the tour was made to carry a large object and participants were bound together for the duration of the walk by a rope. We walked from the Buddhasathan [also known as Chiang Mai Religion Practice Centre] to the night bazaar, a short distance away. There were about seventy to one hundred of us. We walked past a luxury hotel where a wedding celebration was taking place. We then walked past the red light district and solicitous bar girls. We proceeded through the slum where many Cambodian refugees were trying to rebuild their lives, and then through the various neighbourhoods that make up Chiang Mai. We finally ended our walk at the municipal abattoir, where pigs and cows are slaughtered. We stayed on and observed the scene. It was a narrative of great suffering – from dancing and celebration to death.01

As the walkabout’s participants passed through these various domains, the popular image of the Thai city – a tourist’s version of a Chiang Mai defined by its middle-class – was upended. They entered into spaces of uncertainty, where the city’s divisions between social classes and communities were transgressed. Conversation amongst the group became anxiety-ridden at times, yet the rope that bound them together provided a sense that they were in this together, that they had each other to fall back on. 02 In many ways, it also made them aware that their experience was constructed and mapped out in advance, like being part of a tour group, and therefore, in a sense, illusory. The large rocks they were made to carry would have felt exceedingly heavy by the time the tour ended, at daybreak. The journey was meant to be both mentally and physically exhausting.

If all that remains of the artwork is the photographic image and the stories, then what is the object of art history? Photographs are insufficient in that they speak as documents without narrative. According to Siegfried Kracauer, the photographic image does not function as a mnemonic storehouse but rather depletes over time into a surfeit of details; it ‘captures only the residuum that history has discharged’. 03 For an image to make sense, one often has to rely on the account of someone connected to the event (Jai Inn’s narrative above, for instance). It is with these considerations in mind that I wish to propose the art history of social practice as something akin to a set of ‘images without bodies’. This term is moreover used to convey a method or procedure for the art historian, whose task is to reconfigure such histories into potentialities in order to sustain their inherent multiplicity. Of course, scholars writing on the history of performance art have long debated what constitutes their object of study, and such questions are echoed in more recent debates around the genre of art-making known as social practice. For example, Grant Kester speaks of the dialogical nature of such projects; Miwon Kwon describes the precarious nature of site specificity as a medium-generative discourse; Nicolas Bourriaud writes on sociality as a significant facet of scenarios framed in the context of art; and Claire Bishop, as a rejoinder to Kester’s and Bourriaud’s approaches, favours the agonistic dimension of participatory projects that reactivates provocation as a key element within the avant-garde lineage she identifies. 04 In all these accounts, a specific dimension is isolated from a whole range of activities and processes that constitute ‘social practice’, which is then contextualised in relation to established twentieth-century avant-garde trajectories of art history.

Hence, an obvious limitation of these frameworks: the partiality of such histories and their reductive nature. The example of CMSI – just one in a diverse landscape of non-Western artistic practices – immediately invites alternative approaches. How else could we think of a history of social practice so that its complex matrix is not entirely reduced within the narrative of European and North American avant-gardism? Where could CMSI sit other than on the tail end of a global diffusion that began in Europe? Indeed, shouldn’t the methodology be reversed? By using one case study as a focal point, is it possible to more accurately flesh out a different kind of history – a history from within context?

Chiang Mai Social Installation in Context

Chiang Mai Social Installation was a series of four art festivals that took place during the 1990s across a number of public and private non-gallery spaces in Chiang Mai. Principal organisers such as Mit Jai Inn and Uthit Atimana (with operational support from Navin Rawanchaikul and spiritual support from Montien Boonma) conceived it as an art festival that would embed itself within the social fabric of Chiang Mai city. By most accounts, the idea of situating contemporary artworks outside of conventional gallery spaces was spurred by Jai Inn’s visit to Documenta 8 in 1987 – which explored the ‘social dimension’ of art – while he was a student at the University of Applied Arts Vienna. The name Chiang Mai Social Installation, or Chiang Mai Jat Wang Sang Khom, came to be adopted from the second edition onwards. Sang khom translates roughly as ‘a public or a society’, and, according to Thasnai Sethaseree, whose doctoral thesis is one of the very few extended studies of CMSI, ‘Jat wang relates to arrangement of a thing and placing it, it is in a sense a form of “making a space for the public”.’ 05

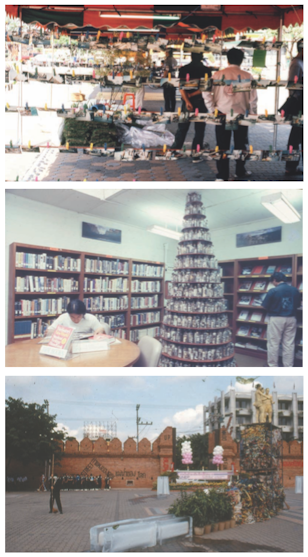

Each edition was different in tone and orientation. The first, ‘Art Festival: Temples and Cemeteries’, was held at the end of 1992, and essentially consisted of sculptural artworks shown in temple grounds and cemeteries. The festival’s evolving aims were sharpened with the second edition, a year later, which moved beyond sacred spaces into the secular. Artists began to enter into a conversation with the city, holding exhibitions and performances in empty shops and local businesses (a dental clinic was one early instance), as well as using the public square outside Tha Phae Gate, one of the main entryways into the historic core of Chiang Mai city, as a performance venue and gathering point. As the festival grew with later editions, it became more ambitious in its attempts to engage with the city’s many publics, from the homeless to small business owners to political activists: projects took place at hospitals, department stores, brothels, the canal, the bridges, even the museum. 06 The roster of participating artists also expanded to include artists from all over the world. Yet throughout, the approach remained self-funded and DIY; for the most part artists covered their own production and travel costs, and public spaces were often occupied without permission.

The genesis of CMSI is intimately connected to Thailand’s modern art history and the institutional challenges that it faced by the early 1990s. European artists had been employed in the Siamese court from the mid-nineteenth century onwards. The Italian-born Corrado Feroci, better known by his adopted name as a Thai citizen, Silpa Bhirasri, arrived in Siam in 1923 to teach sculpture in the fine arts department of the royal court and would become widely recognised as the father of Thai modern art. He played an instrumental role in the establishment of Silpakorn University in Bangkok in 1943 and the National Art Exhibition in 1949, institutions that, in effect, established an orthodoxy for modern art in Thailand. Following the radical student uprising of 1973, which ousted the military regime that had been in place since 1957, the United Artists’ Front of Thailand was established – an arts organisation that responded to the revival and dissemination of Thai Marxist Chit Phumisak’s call for an ‘art for life’ (Sinlapa PhueChiwit). 07 While he derided European modernism, Phumisak did not prescribe a stylistic model, other than calling for social revaluation as central to the artistic paradigm.

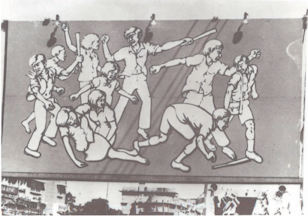

In 1975 the United Artists’ Front of Thailand responded to this call, insisting on the democratic opening of Thai public space by staging a temporary exhibition of billboard artworks along Ratchadamnoen Avenue, a historically significant thoroughfare in Bangkok. 08 Ratchadamnoen Avenue had been constructed in the early twentieth century at the behest of King Chulalongkorn to connect the Grand Palace to the Dusit Palace. Subsequently, under the military regimes of Plaek Phibunsongkhram (between 1938–44 and 1948–57), which were antagonistic towards the monarchy, a so-called ‘Democracy Monument’ was erected on the avenue in 1939. 09 The Monument’s significance continues to be contested across the political divide: while it stands as a symbol of military rule for some, progressive anti-militarist and conservative causes alike have rallied around it. 10The regime and the monarchy established a power-sharing arrangement from 1957 onwards, but this came to an end with the latter’s tacit support of the 1973 protests, which converged at the Democracy Monument.

Hence, the United Artists’ Front’s 1975 outdoor exhibition of billboard cut-outs was a celebratory reclamation of a significant site where political contestation had taken place, and in this way, an important precedent for CMSI. Soon after this, the monarchy turned against the student movement and returned its support to the military, leading to the 1976 student massacre and re-establishment of military rule.11 Many students, including members of the United Artists’ Front, dispersed into the countryside. Only once the political situation had stabilised, around 1978, did many of them slowly return to the capital city. By 1979, the regrouped United Artists’ Front of Thailand initiated the Open Art Exhibition of Thailand, as a kind of ‘Salon des Indépendants’ to counter the dominance of the long-established and artistically conservative National Art Exhibition of Thailand. 12 By the late 1980s, the faculty of fine art at Chiang Mai University began to actively position their art school as an alternative to Silpakorn University in Bangkok; 13 other institutions were also beginning to challenge Silpakorn’s stranglehold, including newly established art schools within Bangkok such as Chulalongkorn University and Srinakharinwirot University. In reaction to the close association of Thai neo-traditional painting with corporate Thailand, individual artists began raising questions regarding the nationalist characteristics of contemporary Thai art under the influence of Silpakorn. It is also important to point out that many of the 1970s radicals did eventually become, from the 1990s on, the most strident promoters of royalist conservatism. In light of these fits and starts, the discontinuities of twentieth-century art in Thailand should be emphasised here; all the more so, I will suggest, because the disbandment of CMSI would follow just such a path.

In effect, these historical precedents demonstrate three things: first, the emergence of a political discourse in Thailand surrounding the activation of public space as a site for artistic practice; second, germinating from the dispersion brought about by the student massacre in 1976, the gradual realisation amongst the cultural intelligentsia of a need to decentralise from Bangkok; and third, through the various challenges to Silpakorn, a collective re-evaluation of art and its institutions. Consequently, in the early 1990s numerous unorthodox art movements began building towards critical mass.

If Chiang Mai became a default location for radical intellectuals from the 1970s–90s, during the same period the city also enjoyed something of an economic surge in the form of tourism, compounded by an unprecedented scale of government and private investment, spurring the heritage industry. For the city’s engagement with the global cultural current of contemporary art, these infrastructures laid the groundwork for what anthropologist Anna Tsing has called an ‘economy of appearance’, defined as a rhetoric of spectacle centred on the potential of profitability. 14 Insofar as the founders of CMSI were initially able to draw on Chiang Mai’s newfound image in order to fashion an international image for themselves, it soon became clear that another mode of operation would grow out of CMSI and thwart such cultural ambitions.

Cooperative Suffering

Chiang Mai Social Installation might be said to mark the beginning of a ‘contemporary’ moment within Thai art history. 15 The few existing studies of CMSI touch on the broader socio-historical forces that emerged as counters to Thai modernism, or as strategies to critique what Pandit Chanrochanakit, in his consideration of the Foucauldian performance of Thai nation-statehood, came to term the ‘Siamese diorama’. 16 The artistic lineage of this critique is often couched in relation to a principle figure, the German artist Joseph Beuys. Here, the term ‘social installation’ is said to be an updated version of Beuys’s ‘social sculpture’ to meet the new demands of the 1990s.

Though the organisers of CMSI have mentioned Beuys as a significant influence, such a genealogy remains unsatisfactory. This is partly due to well-known tensions within Beuys’s social-aesthetic model; in particular, the charismatic and singular figure of the artist in Beuy’s work stands in stark contrast to CMSI’s fundamentally collective paradigm. 17 While most works shown in the festival can be attributed to specific artists, when one speaks to former organising committee members such as Atimana and Jai Inn, they continue to downplay individual artworks in favour of the event itself, to the extent that the event-form is privileged. 18 Moreover, CMSI has survived in the public imagination less as an event attributable to a specific instigator or founder. Hence, CMSI is collective in a double sense: it privileges neither individual authors nor individual works.

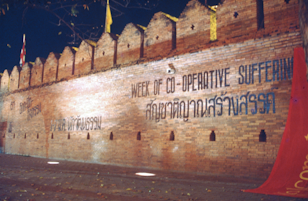

Most of all, what marks CMSI’s departure from the utopian goal of Beuys’s social sculpture is the Week of Cooperative Suffering. This cluster of events, I believe, worked to counteract the main festival, and would be the conceptual catalyst that eventually led to CMSI’s demise. Before the Week of Cooperative Suffering was established, CMSI’s focus had been on staging artworks within public spaces. Yet, according to Atimana, this model was soon perceived as insufficient, especially as the event began to gain attention from the international art world. The first Week of Cooperative Suffering came about through a period of reflection about the aims and direction of CMSI, as well the frustration of dealing with the administrative work of running the festival. With this smaller ‘satellite’ project, the organisers attempted to direct their creative energy towards very different concerns. As Atimana notes, ‘What the people hate, we love. We made many people angry.’19

The first Week of Cooperative Suffering took place in January 1995, between editions of CMSI, and ran from midnight until dawn over a series of nights. In explaining this specific time frame, Jai Inn falls back on a Buddhist story:

When the Buddha was teaching, he was preaching to different constituents of the world at different times. During the day, he taught mankind. At midnight, he taught the Devas (Gods). Some of the Gods even debated with him. That’s why I thought midnight is a good time to initiate a different kind of conversation. We started at six in the evening [and went] until six in the morning. After midnight, there were only drunk people.20

The Week built on a series of events called Midnight Socrates, for which a bonfire was built on regular evenings at Tha Phae Gate, where people would sit around and talk – for example, professors from different departments at Chiang Mai University who did not normally interact with one another. 21 Midnight Socrates was later formalised as Midnight University, and went on to become an important forum for alternative education. But whereas Midnight Socrates and Midnight University were discursive and pedagogic, the Week was more event-based and performative; rather than engaging an audience, it often aimed to shock and provoke; or to entertain, not unlike the night-market performances staged by local stall owners to sell their products. In addition to a session of Midnight University, the first Week of Cooperative Suffering included: a revue of provocative performances and interventions, a night for ‘contemporary sound and light’ (a film screening), a night for installations and a nighttime art bazaar.

The first Week was also the context in which the rock-carrying walkabout (as described at the beginning of this essay) took place. The event was described in the programme as ‘midnight pah-pa’, or ‘midnight forest robe’, a reference to a ceremonial offering from the Thai laity to the Buddhist monastic institution. According to tradition, people would hang rags in the forest as an offering to monks, who would stitch them together for their robes. In more recent times, the ceremony has taken the form of a collection of donations to monastic causes offered along with a robe. The midnight forest robe adopted this traditional symbol of giving while subverting the monetary logic that dominates its contemporary form – the participatory experience was a method to stitch together a gritty tableau, as if the city itself were made of old rags. The midnight forest robe is also exemplary of the very idea of cooperative suffering, since the collective dimension here engendered a crisis of faith. At the time, the Week of Cooperative Suffering was sometimes translated as ‘Angst Week’ – and it was angst that would drive CMSI to ultimately re-evaluate its goals.

The organisers’ anxieties in experimenting with the city would play out in the third CMSI, later in 1995. This was the first time the Week of Cooperative Suffering was introduced into the main festival. With the participation of artists from all over the world, this was by far the best-documented CMSI festival, receiving wide press coverage both locally and internationally, and documented by artists in the form of zines and video recordings. Its DIY attitude brought in a different global demographic in comparison to the kind of exhibition spectacle that would put Southeast Asian art on the global map in the 1990s. 22 The Week of Cooperative Suffering could therefore be understood as a process of making visible the aporia of the globalising trajectory of CMSI. As a dialectic foil to the main event, it was also a mechanism to reflect the organisers’ thinking process as they felt out, and eventually came to terms with, the logic of the global cultural spectacle.

Welcome to Thailand

The expansion of CMSI as an arts festival ran parallel to the festivalisation of the culture industry, as seen in the proliferation of Asian biennials in the 1990s. Prior to this, there were only four biennial-type exhibitions in Asia. 23Beginning with the inauguration of Biennale Jogja in 1988, the 1990s saw the creation of another eight biennials in the region, signalling the moment at which Asian cities began to see the biennial as a viable format to position themselves as regional, if not global, artistic centres. 24 This did not go unnoticed by those involved in CMSI. An observation by American-born performance artist and theorist Ray Langenbach, as part of an artists’ discussion at the 1995 iteration of CMSI, is worth quoting at length:

At the heart of this discussion and the work we … do is a kind of contradiction. I represent a propaganda system. … No matter what my personal view is, I am still that object of propaganda and I carry an ideology wherever I go. … As artists … many of us are attracted to this field[because] there is the possibility of unalienated production. But the problem we face in large part[today is that] we end up being the R&D arm of the new commodities that are produced by our society. … So however radicalised our position … it will be subsumed into the capitalist system, which is a global belief system now. As performance artists, we have even put our bodies into the commodity system. … The ideology of my culture is that I buy you, you buy me. So… all I can say is … welcome to America… but it’s welcome to america… welcome to merica, welcometumerica, welcomtomer, tuh … welcometuhtuh, welcometothailand, welcome to Thailand, welcome to Thailand.25

This slippage in utterance neatly spells out the transformation of the national situation into an international one. It is also an acute observation of the limits of the art festival model under such conditions. After 1995, CMSI lasted only one more edition. According to Atimana, by its third many of the organisers realised that CMSI had outlived its usefulness. If it were to continue, it would be as fossilised cultural spectacle.

It is significant that CMSI came to an end at the very moment that Asian biennials began to proliferate – indeed, at the very moment when CMSI itself was gaining traction on an international level. In the late 1990s, Jai Inn would leave Chiang Mai to start his own business in the Isan region, while Atimana would start running the Chiang Mai University Art Museum and teaching at the university, later leading a media arts and design programme. Thus, CMSI’s demise was not so much a failure to sustain the event on an administrative level as it was a pointed reaction against the festival morphology, a rejection of a certain typology of the spectacular that consumes any space for critical engagement, and of the American-Thai cultural enmeshment (as enunciated by Langenbach) that would parallel the appearance of a globalising art world and its serviceable cookie-cutter biennial oecumene.

More importantly, it would seem that CMSI’s endgame rejects the very condition of coeval equivalence between contexts, which historians such as Terry Smith have taken to mark art production and reception under the condition of global contemporaneity. 26Against such logic, CMSI’s withdrawal suggests an affirmation of its position within a constellation of regional histories, unfolding unevenly, at different speeds. Rather than being absorbed into a ‘global’ contemporary moment, CMSI asserted an understanding of contemporaneity as regional, non-coeval and multiple, arriving at different moments according to specific local conditions. And like its arrival, its dissolution and reconfiguration also speak to this condition of non-coevality. The decision to stop could hence be understood as a protest against the liberal concept of ‘plurality’ itself – and the concomitant idea of multi-temporal coexistence – which ultimately reflects an underlying structural homogeneity despite its appeal to diversity and decentralisation. For the founders of CMSI, the only possible way out of this ‘game’ was to stage a total withdrawal.

Yet, it is not possible to qualify CMSI as a culturally unique phenomenon. By and large, one is able to detect similar gestures taking place across a number of locations across Southeast Asia, each demonstrating similar social practice typologies. It is in this sense that a number of other artist-led collective/event-based happenings across Southeast Asia could be compared in order to shape a regional-historical context in relation to the desire of artists to create new arenas of exchange and encounter.27

This essay enters into the discussion by suggesting that another model of art history for Chiang Mai Social Installation is possible, encouraging a kind of lateral mapping instead of an over-reliance on a chronological canon. For if the history we write is a history for our time, then this lateral history – that would map the event comparatively in relation to other undertakings within the region of Southeast Asia – could offer a different kind of spatial narrative, one that is concrete and public, and yet at the same time strategically disembodied and multivalent.

Images Without Bodies

I have already proposed the notion of ‘images without bodies’ as a means towards historicising such constellations of activity. The materials that survive are less representations than perspectives – interviews, photographs and videos amongst other ephemera; snapshots and afterthoughts, which take on many afterlives. Analogous to Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s concept of ‘bodies without organs’, the work of art history should hence be understood as drawing from this reservoir of possible formations to return the actual event into a state of potentiality – unanchored, in this case, by the historical circumstances that shaped the event’s birth and eventual demise. These are the very same questions that historians of performance and social practice in other contexts grapple with.

Rather than obtain contemporaneous purchase for CMSI through the lineage of the twentieth-century European avant-garde, I have sketched two alternative and complementary possibilities. I have offered a preliminary diachronic sketch stemming from a Thai leftist lineage, which connects the motivations and sympathies of CMSI to the historical gambits of Chit Phumisak and the United Artists’ Front of Thailand. Chit’s appeals to ‘art for life’ resonate with the claim made by Atimana of being a culturalist rather than an artist, 28 which is in turn revealing of the dialectic that spelt out CMSI’s endgame.

I have also suggested a form of critical regionalism – a comparison via a constellation of case studies. 29 Rather than being a pre-existing political unit of examination, the ‘region’ here emerges from a set of specific local contexts and temporary contingencies. Like the very concept of cooperative suffering, this is more about advancing forms of momentary allegiance than erecting geo-political boundaries, to sustain the view that art historical trajectories are always already multiple. As Ahmad Mashadi has observed, ‘Regionality need not be seen simply as a desire for an imagined fraternity. Enmeshing practices, histories and ideals into a crucible of dialogue dismantles the frames and assumptions, unpacking national categories and allowing for cycles of formation and deconstruction.’ 30

A comparative history of this nature is, then, an attempt to seek affinity beyond the confines of the nation state (argued by some scholars to have become art history’s Hegelian unconscious 31) and to allow for new, collective critical sightlines to develop. It is, indeed, a form of cooperative suffering, addressing a kind of knowledge transformation stemming from patience and labour, doubt and angst – and stubbornly local. Like the binding together of the participants from various backgrounds in the walkabout described by Jai Inn, this offers a path that traverses boundaries.

Chiang Mai Social Installation is the point of departure for the two-day symposium ‘Regions of the Contemporary: Transnational Art Festivals and Exhibitions in 1990s Southeast Asia’, University of Melbourne, 5–7 November 2016, organised by Afterall in collaboration with the School of Culture and Communication, University of Melbourne, which will test ideas for forthcoming books in Afterall’s Exhibition Histories series. The author and editors would like to thank David Teh for his feedback during the development of this essay.