In his book The Play of Nature: Experimentation as Performance, Robert Crease examines the similarities between scientific and artistic processes and concludes that they are essentially similar in their performative aspect.01 Judith Butler suggests that gender is also a performative act, one that is played out by each of us as individuals in the public space. 02 Meanwhile, certain readings of Hannah Arendt claim that the body is constructed in performance and is therefore politically charged in the ‘social’ sphere that Arendt sees as the middle ground between the public and private realms.03 All these theorists seem to point towards an expansion of the idea of performance and performativity out of the theatrical and into social conditions. This liberation of performance from the formality of the proscenium arch stage has been grasped by an, increasing number of artists as a renewed site for experimentation. Interestingly, this work has mostly been carried out under the nominal title of visual art, an indication perhaps of the permissive territory of the visual in relation to other traditional art forms. As much as the ‘death of painting’ continues to muddy the waters of contemporary art practice, it is in reality this permissive attitude to media and forms of producing and presenting that has energised art over the past twenty years.

In terms of the practice and theoretical discussions around art, it has been the (sometimes literal) introduction of the body of the artist or writer into his/her work that has effectively challenged the formalist artwork and objective criticism that preceded it. The steady expansion of the idea of performance has been a response to the increasingly persuasive view that the world is in some measure created by the conscious individual through a limited, subjective and active engagement with external reality. The human subject then becomes a ‘site-in-time’ that both projects meaning and has readings placed upon it. Performance permits these contingencies to be made apparent in the duration, immediacy and the context of the artist and audience in a shared space that may or may not be transformed into a stage.

Today, these conditions are not confined to the ‘live’ experience in the way they might have been in the 1960s and 70s. If the fictionalisation of everyday life implied by Butler, Arendt and others, challenged the separate realm of live theatre, then the growth in media forms and images from the 1990s onwards confused the idea of live and recorded as perceptually different categories. Even a notion as apparently unsuccessful as virtual reality at least undermined ideas of authenticity in performance as much on technological as theoretical grounds. Certainly, the effect of video as a cheap, effective reproduction of moving images is in the process of changing performance much as photography changed the space for possibility in painting. It is the video camera as eye, linked to a single consciousness as subjective as any other, that carries the convention of the theatrical onto the screen. From pop television programs such as the UK’s ‘You’ve Been Framed’ to an artist like Hilary Lloyd, the video camera provides a way of recording the everyday and then theatricalising it for a knowing second viewer. By taking the banal and awarding it significance, it underwrites a levelling of experience between private and public that stands for the theatricalisation of society more generally.

The paradoxical intimacy and publicness of performance, reflected both in live events and film or video recordings, weave a loose thread between the artists and projects in Afterall number 3. This issue is grounded by the two contextual essays. Andreas Spiegl takes an insightful look at the conscious theatricality of everyday life and the transformation in the identity of the social subject that this might suggest. Bert O. States examines of the history of performance as a metaphor for actions out with the theatre. This latter essay is republished from a US theatre journal to provide a mainly visual art readership with an insight into current drama theory.04 In its approach, it also seems to argue for the replacement of the theatrical experience with one much more familiar to the art audience, where meaning is produced as a collaboration between artists and viewers as mutual ‘actors’ performing around a work (of art).

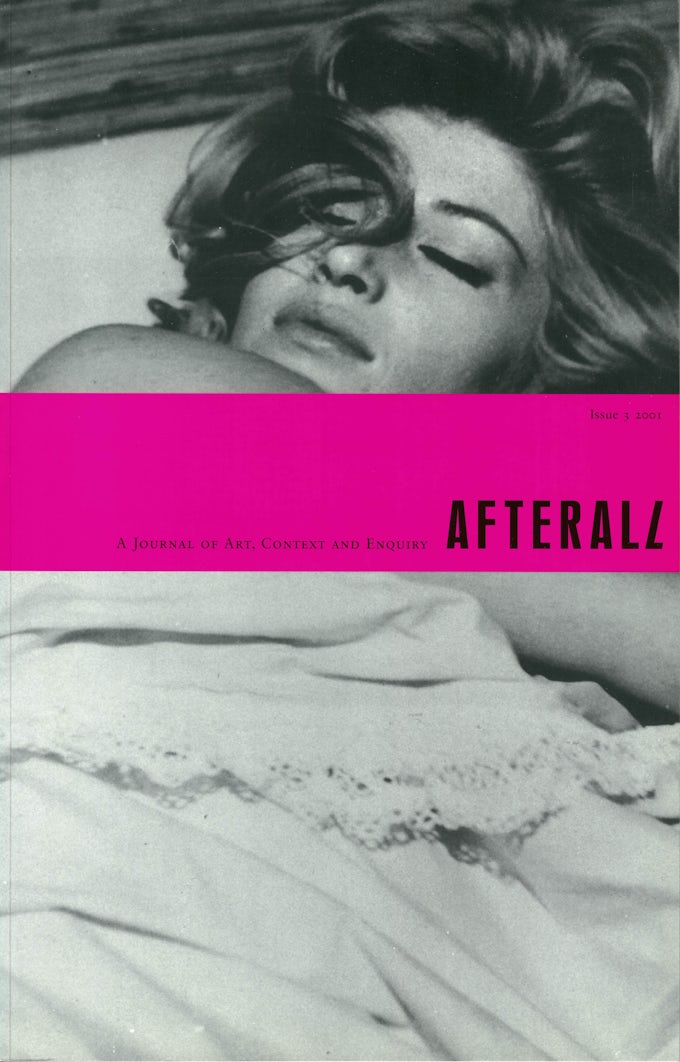

In a change from our familiar structure, we have invited two artists to create projects specifically for the journal. Juan Cruz and Ceal Floyer comment on the viewer as actor and the peculiarly reified status of the audience in contemporary art as opposed to its rather more random claim to attention in any real situation. The use of current recording media, particularly digital video, as a way of representing and recontextualising single, unrehearsed performances is apparent in the work of both Hilary Lloyd and Uri Tzaig. Lloyd’s slow, rhythmic monitor installations are looked at by David Bussel and Jan Verwoert as portraits, short scripted actions, poses and personal landscapes amongst other interpretative possibilities. Sarit Shapira has analysed Tzaig’s work largely in terms of the political context in Israel and the extraordinary bifocality of a society in which almost every event, monument or simple collective activity has an alternative way of being seen. In this context, Pierre Leguillon has chosen to create a precise visual essay, collaged from images of the artist’s most recent exhibition in Frac Champagne-Ardennes. The third artist, Michelangelo Antonioni needs no introduction. As one of the leading film directors of the post-war period, his work reflects the investigative thrust of European cinema in the 1960s and 70s. Even in his earliest works, his use of silence and minimal, repetitive gestures marked him out and he has continued this pursuit of cinematic atmosphere throughout his career. Looked at through the eyes of a contemporary art viewer, his films appear both innovative and familiar. He often constructs images that leave the viewers space to tell their own stories in ways that mirror artists such as Hilary Lloyd’s fractured, uncertain narratives. Finally, we look at the work of US artist Karen Kilimnik. Her installations may use a wide variety of media but they always still seem to revolve around painting and the subjective rendering of an image. Both Barbara Steiner and Caiomhín Mac Giolla Léigh examine a range of work from the overt theatricality of An Antechamber to the Year 1650 from the year 1640 to the playful, self-portraits as various identifiable pop icons. Again, Kilimnik’s work questions the centrality of the artist’s position in the face of the viewers, their memories and their own affection for the celebrities she depicts. Is she an over-achieving fan or a vehicle for a more critical viewing? The question remains open.

As with previous issues, Afterall number 3 does not attempt to create a coherent picture of its ostensible subject – this time the relationship between contemporary visual art, media and performance. By featuring these six individuals, we hope that the artists can be read and thought about primarily in terms of their own work and influences. Likewise, the contextual essays stand on their own. However in the mix of opinion, description, illumination and occasional inspiration, we hope that each reader will enjoy making up their own connections, treating this journal as, if you like, their own mental stage. The metaphor of performance often permits visual artists to think more about the audience and its responses than the creation of an object. We will finish with Roland Barthes, one of the great modern thinkers of performance and the act of viewing. ‘How could we believe… that the work of art is exterior to the psyche and history of the man who interrogates it? … Criticism is not at all a table of results or a body of judgements, it is essentially a activity, i.e. a series of intellectual acts profoundly committed to the historical and subjective existence (they are the same thing) of the man who performs them.’ 05 As two ‘subjective performers’, we would like to hand over this journal to our fellow actors, the readers.

Footnotes

-

Robert P. Crease, The Play of Nature: Experimentation as Performance, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993, p.96.

-

Peter Osborne and Lynne Segal interviewers, ‘Gender as Performance: An Interview with Judith Butler’, London, 1993. Originally published in Radical Philosophy, no.67, Summer 1994.

-

B. Honig, ‘Toward an Agonistic Feminism: Hannah Arendt and the Politics of Identity’, in Feminists Theorize the Political, New York: Routledge, 1992, pp.215-35.

-

Bert O. States, ‘Performance as Metaphor’, Theatre Journal, 48.1, 1996, pp.1-26.

-

Roland Barthes, Critical Essays, Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1972, p.257.