Preamble

No audacity has shaken the conceptual foundations of Congolese plastic arts as much as the revolt that marked the end of the twentieth century in Kinshasa. To the point that it evoked

the ‘Dada phenomenon’,01came to be called ‘bad art’,02 or even became recognised as ‘a new philosophy of art’.03 Embraced by an entire generation of young independent or budding artists, this revolt was crystallised and brought to the public eye in June 1996 by the Free Exhibition Group (Groupe Exhibition Libre), which later became the Librist Group (Groupe des Libristes) in October 1997.

The concept of Librism was coined by the young Francis Mampuya, who at the time was a student at the Académie des Beaux-Arts de Kinshasa. It was used to describe the deliberate struggle that he and his colleagues engaged in against the confinement within academic artistic conventions in favour of blooming free expressions.

In the 1970s, when AICA (International Association of Art Critics) had its first encounters with Africa, the Congolese section had a hard time rallying people around this kind of struggle. The call made by the young section in 1972 for the establishment of an artistic research group was simply ignored by the academicians, whose motto was ‘Down with thinking, long live practice!’ But the debates initiated at the Third Extraordinary Congress of AICA in 1973, which deemed Congolese art as being 50 years behind that of the West, led to the formation in 1974 of the Groupe des Avant-Gardistes Congolais (Congolese Avant-Garde Group, then Zairian). This group aimed to renew modern Congolese art on the basis of ancestral aesthetic resources. This resulted in two major tendencies that were respectively named Neonegrism (Néonégrisme) and Neorupestrism (Néorupestrisme). The first tendency included artists such as ceramicists Bamba Ndombasi Kufimba and Mokengo Kwekwe, painters Mayemba Ma Nkakasa and Mavinga Ma Nkondonguala, and sculptor Tamba Ndembe. The second tendency was led by the painter Kamba Luesa. The approach of the avant-gardists remained consistent for about a year, during which friendly meetings with critical exchanges were organised with the members of AICA/Congo (Zaire at the time). However, a split became imminent. In 1975, clientelism seized upon artists once again. Congolese avant-gardism dwindled either by establishing new aesthetic ghettos or by revitalising the methods of late nineteenth-century Western art. Those who favoured this art had a penchant for exploring ‘artistic attitudes’, highly regarded by fine arts enthusiasts. Their aesthetics typically displays impassive human faces, plastic beauty taking precedence over literary themes. It is, therefore, an art of evasive contemplation. This art contrasted with contemporary popular painting.

Contemporary popular painting is a product of urban culture. Its distant origins, however, go back to the late nineteenth century, to the storied murals that adorned rammed earth-made rural huts, depicting scenes reflecting the villagers’ perspectives on the intrusion of colonial civilisation.

Like their predecessors, contemporary popular painters develop a discourse in which the ingenuity of language is employed for social communication. Most of these painters are self-taught and practice an approximate and naive form of realism. Some, however, have achieved a high level of drawing skill and work in hyperrealism. Considered a minor art form for a long time, contemporary popular painting in the Congo went through a significant turning point after 1978. In that year, the International Congress of Africanists (CIAF) organised a conference in Kinshasa on the theme ‘Africa’s Dependency and Ways to Remedy It’, with the support of the Congolese section of AICA. The CIAF conference was accompanied by the first official exhibition of Congolese popular painting. Held at the Academy of Fine Arts, this exhibition revealed to visitors a pictorial universe proceeding on the basis of a different cultural model. It vividly combines the resources of various visual and literary arts. The appeal of popular painting led some young academicians to convert to it to break free from the confines of academicism. Today, former academy students like Chéri Chérin, Alpha and Mbikulu can be found in the world of artists like Chéri Samba, Camille-Pierre Pambu Bodo, Mosengo Shula, Sim Simaro, Chéri Benga and more.

As for the succession of the avant-gardists, it has been taken over since 1992 by the [Roger] Botembe workshops, where artists like Frank Dikisongele, Papy Malambu Malambu and Denis Matemo also operate. Teaching at the Academy of Fine Arts, Botembe took a sort of sabbatical leave in 1996 to focus on his research into traditional African art. The artist goes beyond the concerns of his predecessors. While the avant-gardists were limited to reshaping ancestral plastic forms, Botembe strives to perceive their symbolism. He uses African symbols to create a new language that can rightly be coined Symbolist Neonegrism (Néonégrisme symboliste). The artist himself claims to adhere to African Trans-symbolism (transymbolisme [sic] africain). This concept is still subject to controversy. Nevertheless, the artist’s approach has real merits. Botembe reconsiders the decorative function of the painting to make it suitable for introducing the public to the intricacies of encoded ancestral wisdom. Moreover, the artist resists the trap of a new academicism.

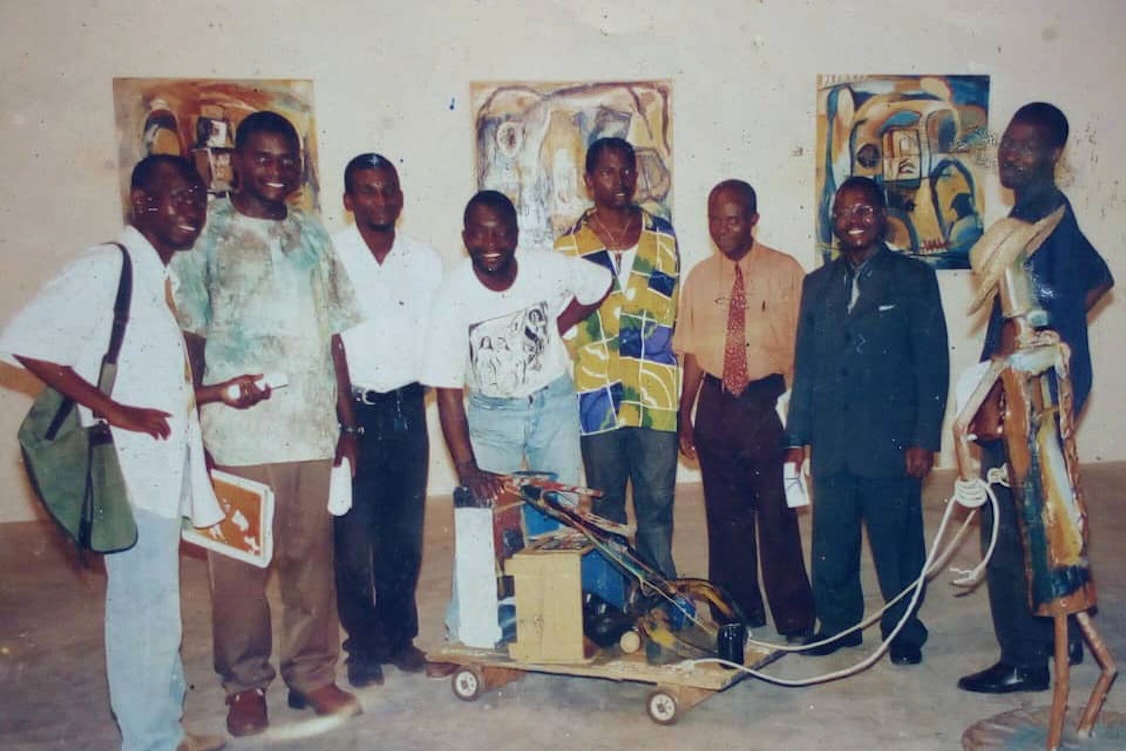

Compared to the experiences of the avant-gardists and the Botembe workshops, the Librist Group, the newest of the Kinshasa-based groups of academically trained artists breaking away from convention, inaugurated, for contemporary Congolese art, the era of radical deconstruction of Academy art (not to be confused with academic art). The founders of the group, Germain Kapend, Francis Mampuya and Eddy Masumbuku were considered ‘rebel students’. Despite their rejection by academic circles, the collective soon expanded with other adherents of Librism, including students Olivier Matuti, Jean-Pierre Katembue, Désiré Kayamba, and Nganga Puati, as well as the independent artist André Lukifimpa, one of the forerunners of the Librist spirit who joined this group in 2000.

The Librists do not belong to a school but rather to a coherent yet non-alienating collective. All were educated at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kinshasa. With the exception of Lukifimpa, whose rebellion came after his alma mater graduation in 1986, it was during their academic curriculum that these artists distanced themselves from non-deviant knowledge and practices and embarked on their artistic battle.

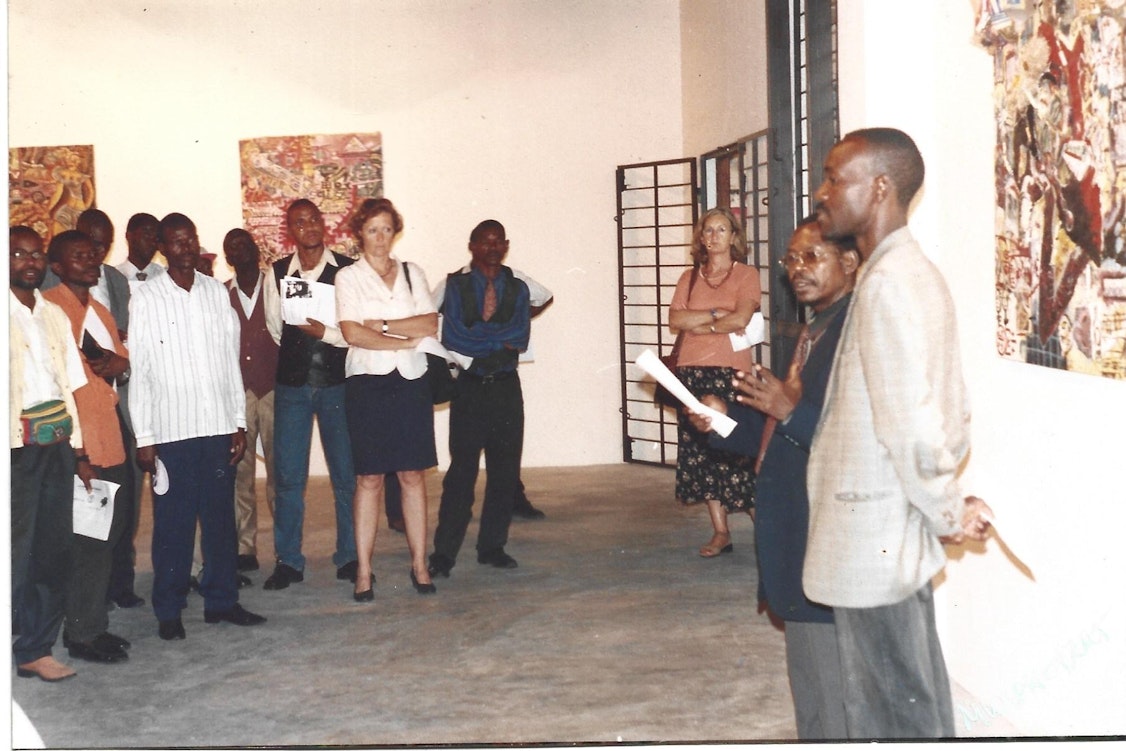

The constant commitment of the Librists to embrace contemporary artistic changes has nurtured and continues to nurture reflection within Espace Akhenaton. This ‘creative workshop’ in the heart of Kinshasa has provided Librists with a place for open, critical and free debates conducive to the trajectory of their creative process since 1997. This approach introduced concepts like, among others, recuperation, performance, everyday objects, installation, painting-sculpture, minimal art and outsider art into Congolese art. With the collaboration of the Halle de la Gombe (French Cultural Centre) and the Wallonia-Brussels Centre, Espace Akhenaton has brought this new Congolese art to the public.

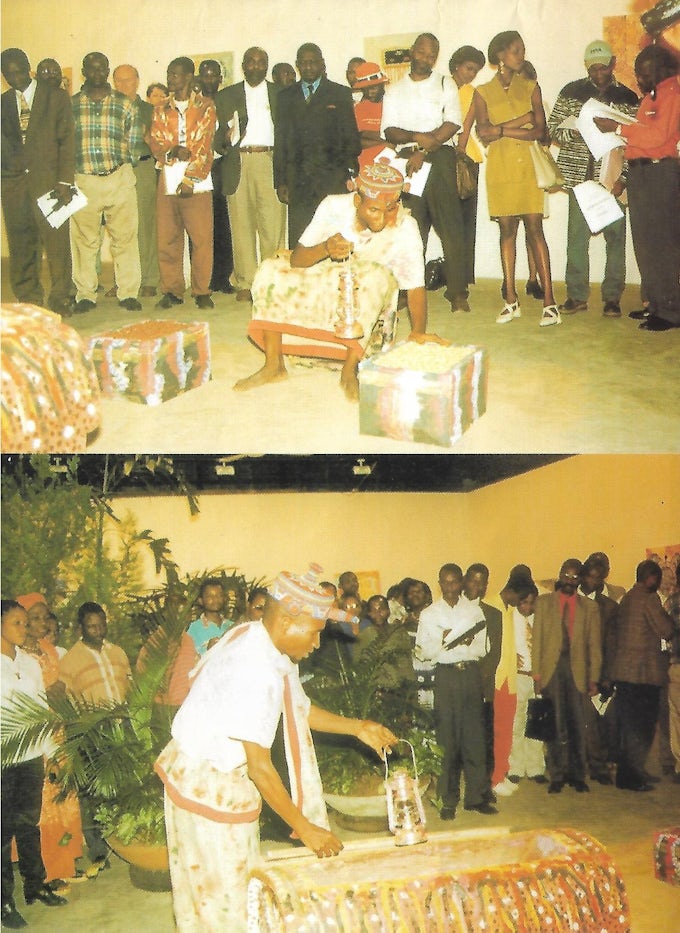

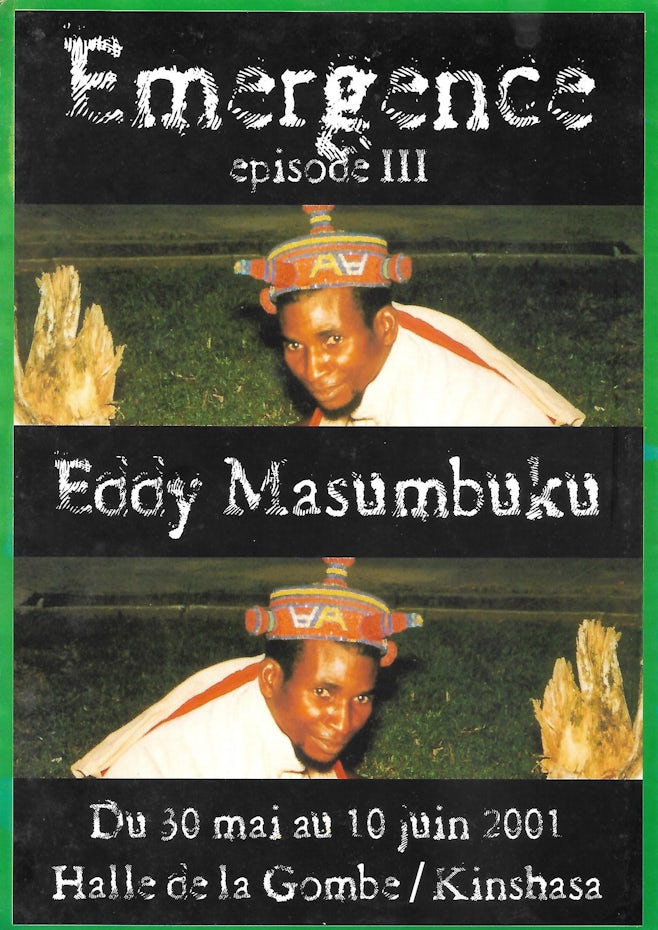

It dedicated its monographic festival ‘Emergence 2001–2002’ to Mampuya, Kapend, Masumbuku, and Katembue, each of whom was showcased in turn in the installations at the Halle de la Gombe, while the ‘Coup de Cœur’ section of the Wallonia-Brussels Centre featured Lukifimpa in its Magritte room.

The following communication seeks to propose what can be considered the initial phase of Congolese art in the early twenty-first century. We are aware of the risks involved in such an exercise, but we leave the definitive judgment to history. To illustrate our point, we have chosen five artists whom we had the privilege of presenting to the public in Kinshasa as part of our cultural activities in support of the young Librist Group’s practices.

Five Influential Figures

Germain Kapend

Sequences of a nightmarish sleep! Kapend’s paintings give the appearance of it. However, this is by no means psychedelic art.

Kapend enrolled in the Academy of Fine Arts in Kinshasa in 1988, where his Librist rebellion began. It gained full strength in 1996 with the establishment of the Free Exhibition Group, where the artist developed a unique language that combines scientific knowledge and Surrealist-inspired visual constructions, constellated with equations and various scientific formulas emerging directly from the unconscious.

The key? One day, in a medical laboratory, Kapend fixed his eye on a microscope for the first time. The cellular universe! What an abundant and teeming life! But what order as well! Perhaps human, animal, plant, mineral and celestial anatomy are all mathematical! Yet, what confusion in human society, despite scientific and technological advancements! Where do the lights of modern science lead us? Mathematics, chemistry, biology . . . ?

The conquest of space, the pursuit of power, the conquest of women, conquest . . . always conquest . . . Kapend rises up, asserting that the drift of scientific genius has resulted in the dehumanisation of contemporary humans who have become masters of the art of destruction.

Kapend’s art is highly urban. Palettes of fire and blue form alternative sets. The madness of the city, the delirium of urban life, can be reminiscent of the graffiti art born in New York in the mid-1970s. Bodies are adorned with a multitude of artifices that penetrate flesh and soul, tattoos made of mathematical formulas and diabolical scarifications.

In many of his works, grafted shards of mirrors invite the viewer to enter the paintings. The unfinished shapes invite them to take part in the creative act, and to mentally complete the anatomies. On some canvases, the artist leaves traces of his own body – hair, beard signs of introspection and of becoming conscious of existence,

a process the artist calls maïshisme. This term is derived from maïsha meaning life or existence in Swahili, a language widely spoken in Lubumbashi, where the painter was born on 30 November 1964.

In his paintings, you can discern the hallmarks of a genuine ‘African urban culture’ that spares neither its ancestors nor its ancestral beliefs. One doesn’t know where to look. As in the heart of the urban jungle, one always misses something, one can neither see nor be everywhere.

How can one hook or direct one’s gaze? Perhaps with a few linguistic artifices: close-ups, superimposition, rotation, or even a 180° bodily twist, which impart to several of the paintings

a multipolar perspective.

A seductive power, an invitation to party, an apocalyptic nightmare, a kind of ‘reasoned’ debauchery – that of the love for the other and of the hope of one day seeing science ‘humanize’ itself.

Exhibition: ‘Emergence’ at Espace Akhenaton, in collaboration with the Halle de la Gombe, 3–13 April 2001.

Jean-Pierre Katembue

In Lubumbashi, Katembue was a student of Mwenze Kibwanga. His art is an eloquent testament to the collision between the Kinshasa academism and the pictorial freedom of Lubumbashi, of which he revitalises the linear figuration.

A member of the Librist Group, he garnered public attention starting from the Dialogues Workshops at the Halle de la Gombe (French Cultural Centre in Kinshasa, 1999–2000). His vigorous lines and refusal of decoration serve as a visual counterpart to Katembue’s fiery temperament. It is also the best way for the artist to contain and channel the binary impulses of his spiritual and even nervous forces. Polychromy is rarely used; when it is, it is often subdued through misty, monochromatic hues, as ethereal as dew. His preferred palette, occasionally torn by vivid, tear-like sprues, is monochrome, in China ink or acrylic, which gives the black line against the white background its full expressive power – whether it’s the outline of figures, always schematic and powerfully frontal, or the abstract meanderings that transcribe ‘the traces of Man’

in his constant quest for spiritual elevation towards infinity.

Katembue’s vision of the world is thus a linear one. According to him, it is reduced to a point and a line. This line helps him apprehend characters in their essential schema. This linear reduction exacerbates the expressiveness of his characters with empty, revulsed gazes and a hieratic stature.

The same line unfolds in a play of straight lines, curves and counter-curves to make the subtle vibrations that cross space sensible. Elsewhere, this line unfolds in a spiralled form that emphasises the gyratory movements of thought conquering space, or generating beings.

Katembue thirsts for plenitude and infinitude. He places his approach under the vigilant eye of the thinking principle that sees everything, and whose symbol, the ‘eye-point-oval’, is present in each painting and sculpture.

Always in search of a better expression, Katembue’s linear reductionist approach has shaped his evolving desire to appropriate space, non-void because it is traversed by the energy of thought. He has gone beyond the boundaries of two-dimensional art to translate his language into sculpture, which allows him to revalue his vision of a simple world through equally simple materials: plaster substitute, moulded iron bars and lacquered planks. Sculpted lines in reinforced concrete erect hollowed-out figures on the pedestal. Elsewhere, they unfurl spiralled thought or speech into space. Drawn black lines traverse the whiteness of concave reliefs or parallelepipeds. The linear universe sometimes creates an interweaving of planes arranged into tangible or visual volumes. This is Katembue’s current step of self-surpassing, where Siamese figures or androgynous beings emerge as a strong expression of the aspiration for plenitude.

To be sure, this is just a first step towards other unexpected audacities.

-

Francis Mampuya, during ‘Émergence episode I’, held at the Institut Français de Kinshasa with Germain Kapend, presented by Célestin Badibanga ne Mwine -

Germain Kapend, ‘Émergence episode II’, 2001, at the Institut Français de Kinshasa

André Lukifimpa

Lukifimpa is a sculptor who embarked on voluntary seclusion for nearly twenty years to find a path that diverged from the 1970–80s trend when bronze and brass were the preferred materials in modern Congolese sculpture.

After graduating from the Academy of Fine Arts in 1986, the artist turned his back on the exhibition hall of the institution and cloistered himself in his home in the modest commune of Bumbu in Kinshasa. He dedicated his days to the observation of the environment littered with various discarded materials, such as sheets and scrap metal from various sources: cars, bikes, household utensils… Beyond this indecent disorder, the sculptor perceives opportunities for ennoblement. He draws inspiration from his own personality and from his practice of martial arts and music, and his training as a visual artist. Three elements become the cornerstones of his production: structure, colour and composition.

These elements are orchestrated in a contrapuntal manner. Massive structures come together with filiform ones. Austere shapes are articulated with supple ones. The colours aim for purity, creating chromatic counterpoints that resonate like true accents intended to strengthen the structures they raise. The orchestration of structures and colours festively evokes the grand compositions of instrumental music, where dense spaces are articulated with airy spaces. This gives Lukifimpa’s sculptures a rhythmic breathing quality that radiates a sense of monumentality. Regardless of the dimensions of the works, whether small, medium, or large, they all possess an airy and spatial appearance.

Before scores of assemblies with geometric carvings, it feels as though one is witnessing a three-dimensional kaleidoscopic unfolding, akin to a transmutation by Wassily Kandinsky: rhythmic structures harmonise with colours in space.

And when the artist lets the raw rust of iron have free rein, the composition blends airiness, monumentality and material effects to the point of enthralling the imagination, diverting it from the danger represented by the sculpture’s ephemeral resistance to

the elements. Art restorers have some work ahead of them.

Sometimes, everyday objects create ‘objective’ cuts in the sculptor’s abstract universe. The visitor is drawn back to the immediate environment, with the recycled discards serving as symbols. Padlocks, lamps, handlebars, rear bridges, brake bands, pots, rims . . .

What is more, Lukifimpa’s various sculptures reveal their ultimate purpose, which is to be created on a large scale to reorganise the environment, making it liveable.

Francis Mampuya

Mampuya’s spirit and heart are in search of human reconciliation. This is evidenced by the theme of faces that is recurrent in his works from 1998 and 2000: a leitmotif with which he adorns his canvases and sections of polychromatic sculptures; a cliché signifying both the diversity of humanity and the unity of humankind; a true aphorism whose resonance challenges contemporary consciousness regarding the ills brought about by the absence of interpersonal and intercultural communication. Despair, desolation. Chaos.

The artist thus places human communication at the heart of the social discourse, where the key for each person lies in learning to communicate with their inner self.

Oval contours, multipolar compositions and the spreading of warm and cold colours: an awareness of the essential attraction of elements. Unity and attraction that only speech can generate… A difficult but achievable task. The presence, albeit rare, of serene profiles, ‘accomplished’ individuals, is indeed evocative in Mampuya’s work. As with the faces, the spaces are seldom in a state of stability. A difficult but possible fulfilment of the true global village where everyone can speak freely together and invite one’s counterparts.

The 2000s announce some elements of response to the persistent questions posed by the artist. A face-to-face with his dreams, fears, and fantasies. The exploration of oneself and of the environment in order to discover the potential forces capable of transforming humans from ‘consumers of everything at all times’ into beings who create meaning.

Eddy Masumbuku

Masumbuku grew up in his hometown, Mangai, where he was born on 3 October 1965, in the Bandundu province. His adolescence was marked by an ‘all spiritual’ diet: traditional tales, imbued with ancestral wisdom, and the study of subjects such as mathematics and physics, as well as philosophy that he discovered during his secondary education, shaped a critical yet serene mind.

In 1985, while still a high school student, Masumbuku rebelled against the fatalistic and resigned mindset of his fellow citizens in Mangai, who believed that the hardships they faced were solely a result of ‘politics’: ‘That’s just the way it is,’ they would say. Masumbuku disagreed and decided to make his disagreement known.

This rebellion symbolised his break from the official ideology of the time, known as ‘authenticity’, which, in his eyes, caused collective intellectual anaesthesia. Masumbuku sought to reclaim his original identity despite the political constraints of the era, and he rejected his Zairian post-surname Alungula, replacing it with the pseudonym Eddy.

After earning his high school diploma in 1988, Masumbuku enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kinshasa in 1989, majoring in advertising. However, the challenge he faced was to fulfil his dream of excelling in expressive painting rather than advertising illustration. Starting in 1995, he spent his free time illustrating children’s books, focussing on themes such as the wisdom of village children and riddles. However, these pastel sketches soon revealed their limitations,

as the medium did not allow the artist to fully express himself.

The turning point came in 1996 during Masumbuku’s first true experience in painting with a brush, which he created with the assistance of a fellow student, Francis Mampuya. The first real painting The Curiosity of Knowledge was born.

This theme announced the fundamental content of Masumbuku’s art: a plea for knowledge. In 1996, he also shared his idea with Mampuya and another fellow rebel student, Germain Kapend, to create a group of young artists breaking away from academic art. In the same year, the Free Exhibition Group was formed, with the three students as its founders, adopting the name suggested by Mampuya. Following another proposal by Mampuya, they renamed themselves the Librist Group in 1997. Within the collective, Masumbuku found support for his moral, intellectual and artistic struggles. His art is open to any critique that could illuminate his own quest for identity.

For Masumbuku, ongoing learning is the key to individual and community development. He believes that knowledge liberates people and conveys this idea through newspaper clippings found in many of his paintings. Even more subtle is his Fouillism (Rummagism) language, a term coined by the artist. The first painting in this style, Humanity Rediscovered, created at Espace Akhenaton in 1998, marked a turning point in Masumbuku’s developing artistic language, born from his meticulous observation of the environment and nature.

The striations, true pictorial ‘tears’,‘are created from fingerprint impressions that attempt to extract the human form, similar to a rooster digging up sustenance from the nurturing earth. As his work progresses, the striped strokes become a matter of brushes. From being monochromatic and thick during his early fingerprint phase, they are now polychromatic, filament-like and luminous, with

a certain penchant for decoration.

Following a period of reflection, which led him to minimise the decorative aspect in his paintings, Masumbuku delves into the very essence of the phenomena he observes. For example, the moment when raindrops meet the ground inspires the creation of acidic strokes, akin to magma, which make gooey zones erupt from his paintings, representing those that humans encounter when traversing ‘the corridor of knowledge’.

Whether joyous or acidic, uniform or striped, or in droplets, realistic or geometric, Masumbuku’s paintings make tangible the vicissitudes of initiation into humanism. His desire to involve individuals in these initiatory experiences finds its full expression in the ‘performance-installation’ genre, through which the artist engages the public in the creative process.

Future Prospects

Contemporary Congolese art seems to be shaped by the rebellion of young artists against the aesthetic traditions inherited from the academic education imposed since 1943 by the École Saint-Luc

à Gombe currently the Academy of Fine Arts. This education, based on the interpretation of Western academic canons and African statuary, tends to inhibit artistic creativity and maintain traditional aesthetic standards. It is necessary to rethink this pedagogy to allow young artists in training to explore other forms of artistic expression that align with their personalities.

Today, many young people would like to embrace the new technologies of creativity, but workshop masters are clinging to manual craftsmanship. For the time being, only alternative training structures are willing to meet the needs of young talents. This is the case with our Espace Akhenaton, which can support aspiring digital art enthusiasts as soon as interested partners provide it with the appropriate equipment.

Established in Kinshasa in 1989, this centre is notable for its courage in providing support for young creators, even when they face ridicule from the majority of established artists and art enthusiasts. In 1994, Espace Akhenaton introduced the Emergence concept, which serves as a space for encouragement and (re-)assessment of artistic experiences that break with the conventional paths, while also aiming to facilitate intercultural encounters. The 2001 and 2002 editions, organised in collaboration with Halle de la Gombe, demonstrated the relevance of Emergence to the public and underscored the need to diversify partners, in line with the project’s initial plans, to enable it to achieve its various objectives.

Espace Akhenaton is also concerned with the qualitative development of popular painting. It benefited from the collaboration of the French Cultural Centre and the Wallonie-Bruxelles Centre to organise the first edition of the International Popular Painting Crossroads (CIPP– Carrefour International de la Peinture Populaire) in 1994. As the current AICA conference is taking place, Espace Akhenaton and the African Centre for Popular Cultures (CACP– Centre Africain des Cultures Populaires), led by art historian Joseph Ibongo, are pleased to have contributed to the success of the ‘Kin moto na Bruxelles’ (‘Kinshasa heats up Brussels’) exhibition, dedicated to popular painters from the Congolese capital. The artworks are displayed at the City Hall of Brussels and the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren. Initiated by the City of Brussels, the exhibition runs from 5 May to 14 September 2003, with the support of the Wallonia-Brussels Federation and the aforementioned museum as part of ‘Africalia’ 2003. Several requests have been made for the paintings to tour across Europe.

However, the event has primarily emphasised the need for long-term collaboration. This may be the opportunity to make the regular occurrence of the International Popular Painting Crossroads

a reality through a multilateral partnership.

Finally, the longstanding wish of many young artists and cultural operators in the Democratic Republic of Congo, similar to those we had the honour of meeting during the DAK’ART 96 and 98 editions to see Kinshasa host, on an alternating basis every two years, the Emergence concept and the International Popular Painting Crossroads. This will contribute to the construction of new opportunities for artistic encounters and exchanges, as well as the development of intercultural dialogue in Central Africa.

Translated from French (Democratic Republic of Congo) by Adeena Mey. Published with kind permission from Ghislaine Badibanga and the Archives of Art Criticism, Rennes, France. With special thanks to Jean Kamba for his help.

* Paper by Célestin Badibanga ne Mwine ‘Emergence d’une nouvelle plastique Congolaise’, presented at the symposium ‘Art minorités, majorités’, 11pp., 2003. Transcript held at Archives de la critique d’art, France, FR ACA JLEEN the AIC024 04/11, Jacques Leenhardt Fonds, Lina collection.

Footnotes

-

See the art critic Bemba Lu-Babata, ‘Avis sur l’exposition de Mampuya’ [talk], Centre Culturel Français, Kinshasa, 13 March 2001.

-

Adiste Lema Kusa, professor at the Académie des Beaux-Arts, intervention at the conference ‘Librisme: Par qui? Pour qui? Pourquoi?’, hosted by Célestin Badibanga, Paul Nzita, Désiré Kalumba and the Librist, Académie des Beaux-Arts, Kinshasa, 16 July 2001.

-

See philosopher of art Abbé Mudiji, ‘Avis sur l’exposition de Mampuya’, Centre Culturel Français Kinshasa, 13 March 2001.