Georges Didi-Huberman stands out among contemporary authors for his efforts to explore the crossings between art history and philosophical thinking. His referents are numerous in this sense. On one hand, he is an heir to Marc Bloch and Lucien Febvre’s Annales school of historiography, together with theoreticians like Henri Focillon or Pierre Francastel, and iconographers like Panofsky and Warburg. On the other hand, he keeps a fluent dialogue with a tradition that begins with Nietzsche, continues through the writings of Bataille and flows into Barthes, Foucault, Deleuze and psychoanalysis.

The dialectic relationship between these theories – in the manner of a conceptual atlas, it could be said – gives rise to a sophisticated reflection about the present status of the image. Didi-Huberman assumes, with Barthes, its capacity to bear testimony of the ‘real’, but he articulates and counterbalances this trustful attitude towards representation with a measure of suspicion, drawing from such authors as Guy Debord or Jean Baudrillard.01

This framework implies that Didi-Huberman never refers to an ‘image’ singularly, but to images as a group, and more importantly, to the way in which they are organised and the different accounts they provoke through their montages – an essential concept in his work in general and in the ‘Atlas: How to Carry the World on One’s Back?’ exhibition in particular. Images are always relative and fleeting in Didi-Huberman’s theory: they perform precise functions in specific contexts. They are symptoms or gestures with an incomparable historical value, that help us to think and take a position in front of the real.02

Before he worked on the ‘Atlas’ exhibition – shown at the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid last winter – Didi-Huberman already had investigated other collections of images which could be considered as partial approaches to the general project that he dedicates now to Aby Warburg and his Mnemosyne Atlas (1925–29) in an exhibition format.03 This is the case with Didi-Huberman’s publication on the Salpêtrière hospital and hysteria in the nineteenth century, for example.04In other projects, his interest focused more specially on images as a vehicle to show past traumas, as in the book he wrote on four pictures taken by members of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Sommerkommando, documenting the extermination methods used by the Nazis on that concentration camp.05

All these experiences came together in the exhibition at Reina Sofía – using a medium in which Didi-Huberman has occasionally practiced in before, and which provides new readings on his own work.06 First of all, the exhibition allows for a performative display of Warburg’s notion of a discontinuous and non-linear time, in which artworks from different epochs are unexpectedly juxtaposed – here the display rejects history’s narrative as an ordered sequence of successive events. Secondly, and concomitant with this non-chronological concept of time, the exhibition characterises itself as a multi-dimensional idea of space. ‘To make an atlas’, Didi-Huberman writes in the exhibition press release, ‘is to reconfigure space, to redistribute it, in short, to redirect it: to dismantle it where we thought it was continuous; to reunite it where we thought there were boundaries’.07 In a museum context, this conceptualisation of time and space comes out as a challenge and a stimulus, towards reconsidering the work within a collection that already has a wide historical scope (such as Reina Sofía’s); such an account is inevitably transformed when looked at through the perspective of this spatially enacted atlas.

Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas anticipated this interpretation of history in the beginning of the twentieth century, when it to produced – to paraphrase Foucault – an ‘archeology of the visual knowledge’, which Didi-Huberman picks up again now.

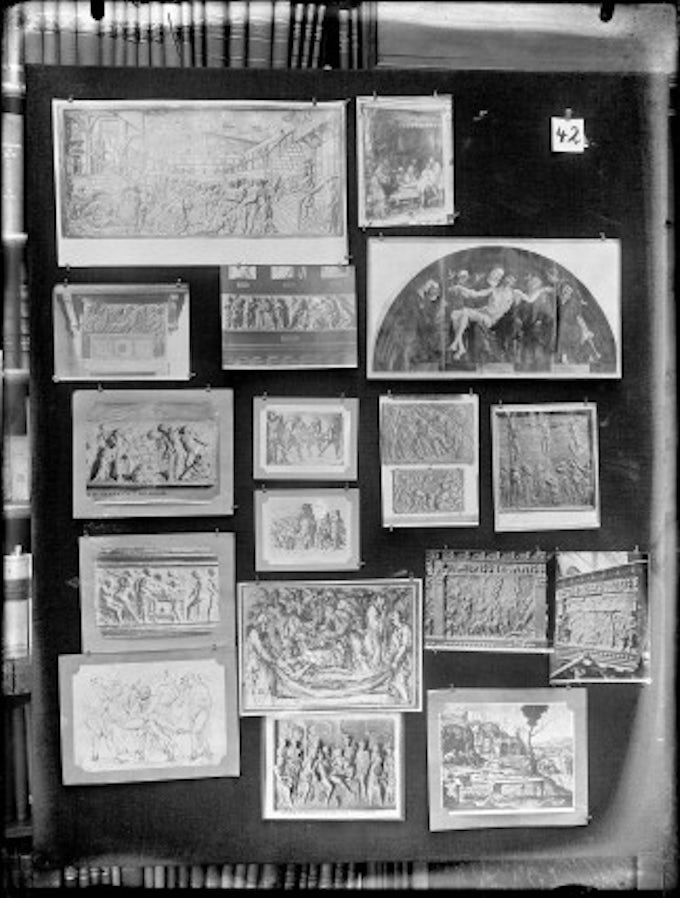

As conceived by the German art historian in his library and working place in Hamburg, before being smuggled to London to protect it from the Nazis, the Mnemosyne Atlas was a kind ofdispositif situated halfway between the pedagogic and the theatrical. Its modus operandi was simple. Warburg would attach images with small pins to a black cloth mounted on a stretcher – as if it were a canvas on an easel – and photograph the arrangement to obtain a (potential) plate for the Atlas. Following this, he would dismantle the original configuration in order to compose another mosaic of pictures that would establish new relations among the forms depicted. More so than the Atlas’s content, Didi-Huberman’s exhibition explores this working method – which was revolutionary, creative and pioneering in the fields of art history and cultural studies (and similar to certain referential practices by contemporary artists and curators).

From Didi-Huberman’s perspective, the Atlas is not only a collection of images, but a ‘form of visual knowledge’ and an infinite archive which gains meaning through the concept of montage.08In the period between the World Wars, when avant-garde artists were torn between their passion for photography and cinema on the one side, and abstract iconoclasm on the other – along with his contemporaries Sergei Eisenstein, John Heartfield, Walter Benjamin and the Soviet Constructivists, Warburg explored the dialectic and meaningful relationships that emerge from setting one image next to another. It is this positioning act, revealing and discovering their secret ties, as well as the hidden discourses that are produced in the interstices and which transform the atlas into the opposite to a linear and monolithic narrative.

To develop and analyse this historical and epistemological context, beginning in the first third of the twentieth century and continuing through to the present moment, Didi-Huberman has traced an interdisciplinary itinerary, composed of sections which include both artworks and documentary materials. This trajectory moves through four main areas, dedicated to ‘Knowledge through images’, ‘Piecing together the order of things’, ‘Piecing together the order of places’ and ‘Times’, which are subsequently divided into new fragments.

The display opens with the reproduction of some panels from the Mnemosyne Atlas itself (now kept at the Warburg Institute in London), and a sculpture of Atlas bearing the earth’s globe from 49 CE. Immediately following these, in the first room, the viewer finds a number of documents which condense most of the project’s contents: diagrams, sketches, and drawings that Warburg made to prepare his lectures – such as Luthers Geburtsdatum (Luther’s Date of Birth, 1917) – which advance in a different format his work with the Atlas panels, showing the creativity and freedom he employed to interpret and confront images.

As the exhibition continues, the concept of the atlas is nuanced through different interpretations. Paul Klee’s fragile collection of plants, Pflanzen auf schwarz grundiertem Papier(Plants on Black -Primed Paper, 1930), or a selection of Bauhaus Jahrbücher (yearbooks) from 1923 to 1924, contextualise the exhibition project within the historical avant-garde, coinciding with the moment when Warburg designed the Atlas. However, the show’s weight rests on a certain generation of Conceptual artists who came to prominence in the 1960s and 70s, variously accumulating images, interpreting and organising them, according to their personal experience. On Kawara, for example, created an atlas based on a collection of postcards, each assigned with time, date and place, depicting the different cities in which he woke up every morning from 22 November 1971 to 7 February 1972. In contrast to Kawara’s attention to apparently insignificant events, Gerhard Richter’s photographic series dedicated to the Baader-Meinhof terrorist group members – Baader-Meinhof-Fotos (1977) – represent a version of the atlas as a collection of historically relevant moments which are built in retrospect, in a manner as blurry as an individual’s memories.

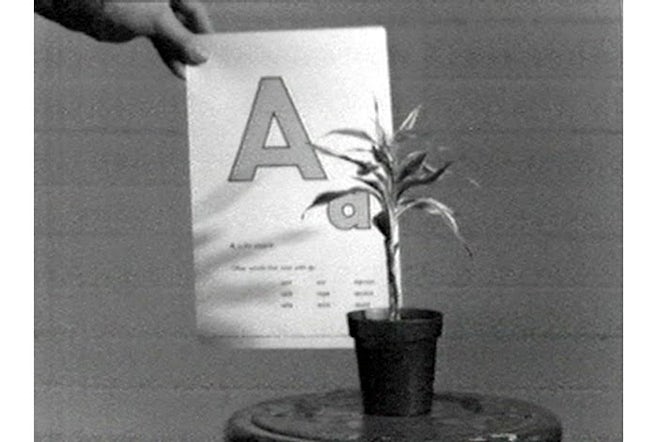

Next to these, Marcel Broodthaers and John Baldessari contribute more humorous visions. Broodthaers presents a miniaturised and ironic atlas illustrated with blank maps of isolated nations, presented as if they were drifting islands, together with the legend ‘La Conquête de l’espace’ (The Conquest of Space). As is usual in his practice, Broodthaers’s piece plays with absurdity and arbitrariness, challenging any taxonomy, classification or abstraction. Baldessari’s contribution is his well-known video Teaching a Plant the Alphabet (1972). Although perhaps not as obvious from this work, Baldessari’s presence is a reminder of the fact that few artists have so successfully exploited archival images, following and renewing – precisely – montage and collage traditions.

Peter Fischli and David Weiss show a multi-screen version of their monumental Sichtbare Welt(Visible World, 1997) project: a disparate collection of images ranging from natural wonders to urban phenomena which fade into each other as if impelled by an alchemic process. Matt Mullican’s Bulletin Board (1998) reflects contemporary social structures through signs, both in their material and virtual levels. His contribution is part of one of the most original subsections of the exhibition, titled ‘The child-junkman-archeologist’, based on the artist as a muckraker, scavenging the remains of repressed and silenced memories. Finally, Walid Raad is represented by a work submitted under the guise of The Atlas Group: Missing Lebanese Wars, Notebook Volume 72 (1996–2002), which responds to World War I images collected by Warburg himself, and which is dedicated to ‘dismantl[ing] the present times chronic, in order to let injustices, cruelties and reason’s monsters emerge’.09

As was the case with Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas, Didi-Huberman’s exhibition shows the paradox inherent in such an ambitious and melancholic undertaking: the hunger for knowledge through images is inextricably related to the impossibility of managing an infinite archive. Didi-Huberman reflects on this situation in a text accompanying the display: ‘The Atlas doesn’t detach objects according to pre-established categories, rigorous definitions, or ideal hierarchies: it satisfies itself collecting, that is, respecting, the great “fragmentation” of the world’.

The 16mm film Encyclopaedia Britannica (1971) by John Latham is, perhaps, one of the artworks that better represents the ambiguity and contradictions of a model of knowledge that aspires towards a totality through fragments. It is in such a fragment that Warburg believed it was possible to find God, expressed his famously espoused motto ‘God is in details’.10Latham’s work shows the encyclopaedia pages flipped through at high speed in a mad, humorous sequence. Close to slapstick, Latham’s film oscillates between an attempt at the accumulation of the (supposedly) entire knowledge of an epoch and an absolute nonsense. Such a paradox could be appropriately connected with Jacques Derrida’s book Mal d’archive (Archive Fever), published in 1995,11 when the World Wide Web and digital technologies were still nascent. Derrida identifies the Kafkaesque, immeasurable and uncontrollable urge to register every single thing, word or image in archives – here presented as an atlas, after a process of decision and selection – while at the same time giving scope to the desire for ruin and blindness that permanently haunts this romantic, vital and limitless excess.

Home page image: Moyra Davey, ‘Facockta Buttons’, (detail) 1996. Courtesy the artist, Murray Guy (NY) and Museo Nacional de Arte Reina Sofia.

Footnotes

-

Pedro G. Romero, ‘Un conocimiento por el montaje. Entrevista con Georges Didi-Huberman’, 2007. See http://www.circulobellasartes.com/ag_ediciones-minerva-LeerMinervaCompleto.php?art=141&pag=1#leer

-

Ibid.

-

Apart from the exhibition and its catalogue, Didi-Huberman is the author of a comprehensive study on Warburg titled L’Image survivante: Histoire de l’art et temps des fantômes selon Aby Warburg (2002).

-

Didi-Huberman, Georges, Invention of Hysteria: Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of theSalpêtrière, Paris: Macula, 1982.

-

Didi-Huberman, Images in Spite of All, Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 2004.

-

Didi-Huberman was the curator of the exhibition ‘L’Empreinte’ (Pompidou, 1997).

-

Didi-Huberman, Georges (ed.), ‘Atlas o la inquieta Gaya Ciencia’, in Atlas: How to Carry the World on One’s Back? (exh. cat.), Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2010, p.14.

-

Ibid. Author’s translation, from the exhibition catalogue. Pp.382

-

See Martin Warnke, “God is in the Details, or the Filing Box Answers”, in Gazing Into the 21st Century, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2011, pp. 339-348.

-

Jacques Derrida, Mal D’Archive, Éditions Galilée, Paris, 1995.