As the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and the various art scenes that comprise it, gains institutionalised recognition, it begins to tell a narrative about itself: to be laid out in museums such as the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi or the theses of PhD students. Like most stories, it’s complicated. The UAE does not fit into a traditional postcolonial matrix – firstly, because the country is so young that it did not have a multi-layered art scene that predated European colonisation, as neighbouring countries such as Iraq, Lebanon or Egypt did. Secondly, thanks to the discovery of oil, the UAE is vastly wealthy, unlike other postcolonial countries in which economic iniquities persist between them and the West. From an art perspective, this means that the artists that populated the UAE’s modern phase, from around the 1960s to the early 1990s, were of varying quality – some of them were amateurs, and others were brilliant artists whose talents were simply undiscovered by Western art power structures. Others diverged from Western categories by operating across numerous fields or by blurring art and ornamentation, and arguably those artists have been considered non-professional simply because of Western unfamiliarity with (or their lack of appreciation for) these formats. Many exhibitions were self-organised, in sites such as hotels, homes, airports and hospitals; the art market was local; and the artists called themselves ‘fine artists’, signalling a non-fluency with the international art field. But the formation of a narrative is also difficult because this process is happening just as assumptions around quality are called into question – a time in which, for instance, Hilma af Klint, long derided as a secondary artist, shares space at Tate Modern with the enthroned Piet Mondrian – by global art history and the many frames of references and assessment it brings into the picture.

This text aims to throw yet another wrench into the works, in focussing on the art produced over the course of six decades by the Palestinian-Emirati artist Feryal Matar. Matar, who was born in 1935 near Nablus and who is still alive, has been incredibly prolific. She has exhibited internationally, and for two years in the 1970s she starred in the first art programme on Dubai TV, Rukn Al Fann, loosely translated as ‘Art Corner’. Her work is in the collections of sheikhs and dignitaries, and she taught hundreds of women at the Sharjah Women’s Association, where she founded and ran the art programme from the 1970s to the 2000s. Yet today the current revival of interest in her work is largely a labour of love by her daughter, Amal Abu Kuwaik, to make sure her mother gets the recognition she deserves.01 In looking at Matar, we see not only a tradition of art-making emblematic of its time, but also a window into the other reasons for visual production – affirmation, empowerment, community – that are often left out of its stories, particularly those among women. If the art world can be mapped by exhibition histories, what happens to the work that isn’t shown?

Matar the Artist

According to her daughter’s telling, Matar was an artist before she even knew the word existed. In Palestine, in the village of al-Majdal, she was constantly drawing and making pictures with whatever material was available – even with sticks in the dirt. After losing her father in the Nakba, Matar and her family fled to Gaza in 1948. Her talent for drawing was discovered there, after she created a portrait of a girl holding a water jar on her head (interestingly, a common Orientalist subject), and from the age of fourteen she taught art in the refugee camps to young children while also receiving private lessons herself. This included tuition from Ismail Shammout, who had returned to Gaza after attending art school in Cairo, and who later became one of the most prominent chroniclers of the Palestinian catastrophe, with his wife, the artist Tamam Al-Akhal.

In the 1960s, Matar travelled to Kuwait to teach art and exhibit her own artwork. There she met Dr Zuhair Abu Kuwaik, another Palestinian refugee, and they married. During their honeymoon in Switzerland, she drew a careful, intricate study of their Alpine chalet, as well as a pencil drawing of herself as a young girl, with a thick braid falling over her shoulder, which she gifted to her new husband. They soon moved further across the Arabian Peninsula to Dubai and then to Sharjah. A contract from 1968, issued to Abu Kuwaik and Matar while they were living in Dubai, states the terms of their move: it would be to assist the ‘Trucial States of the Oman coast’, as Sharjah was then called, and was issued by the general council for the South Arabian Gulf, at a salary of 800 riyals per month – which could be paid, the contract specified, ‘by the common currency of the time’, in an acknowledgement of the ad hoc nature of the economy.02 In this the Palestinians were one of a number of Arab groups – from the Sudanese to the Lebanese – who helped build up the nascent country, taking up roles in teaching, engineering and civil service. Matar and Abu Kuwaik had five children together, and in between these domestic duties Matar pursued formal education: a diploma in Arabic calligraphy in 1967, art at Barnet College in London in 1974, and, at another point in the 1970s, a degree in ikebana in Japan.

When Matar and Abu Kuwaik arrived in Sharjah, in the 1960s, they bought a piece of land inward from the waterfront area now known as the Heart of Sharjah. Abu Kuwaik planted seeds from Palestine, growing olive trees, pomegranates, lemons, mangos, figs, berries, guava, jasmines and oranges in the yard between their main dwelling and a second, smaller, one-storey house. The pair used this house in part to host dignitaries and businessmen who were passing through the growing emirate. They decorated it in traditional style: coir cord lines the ceiling in neat rows; wooden lintels support the doors. A long room on the side of the house had served another function: it was Sharjah’s first medical clinic, where Dr Abu Kuwaik looked after most of the pregnant mothers and their children in Sharjah, bringing his gynaecological and paediatric training to a society that had previously given birth without medical intervention.

This half-guest house, half-clinic was unique for another reason: it heaved with artworks, many of them representing the emirate or using it as a material itself, in neat calligraphy formed of sand and shells from the beach, moulds of the flowers and plants around them, or paintings of the sea. For 60 years, this second house was Matar’s art studio, where she executed calligraphy, embellished abayas, carved wood and painted on oil on canvas.03

Matar’s paintings cross a variety of styles but mostly delight in sheer technical form. (While it is unclear how many lessons she had with Shammout, there are overlaps with his expressive, emotionally attuned style.) She has created numerous landscapes, particularly of the sea, in which she draws out the lightness of the foamy waves or the variegation of blues of the water. This polychromy is often amplified in scenes of high contrasts, such as the view from a cave looking out, in which the calm sea offers itself just beyond a dark and claustrophobic interior. Palestine is an important, constant subject, in a reflection of the strong support and sentiment in favour of the Palestinian struggle across the Arab world at the time, and in Sharjah in particular. Palestinian emblems, such as the Dome of the Rock or the cartographic outlines of Palestine, evoke the horrors of the Nakba and function as symbols for statehood. In what is perhaps her most bravura surviving painting, these two motifs collide, as she imagines an enormous wave that threatens to engulf the dome, its frothy tentacles reaching towards the pointed arches as a brass house-key, which Palestinian women typically wore around their necks to signal their right to return, floats in the foreground.04 She has also veered into symbolism at times, as in the 1990 painting of a cave in which small veiled heads can be seen, like shipwrecked people adrift in the surf, becoming part of the maelstrom. Still others are stylised, with blocky figures that adhere to folk-art style. The work Emirati Girl in Talle (1970) is made out of long iridescent beads, through which Matar has created the image of a woman with two black braids in a black dress with traditional tatreez embroidery, and – in red and white beads – the outline of a city in the background, presumably Jerusalem. In another work of yet another style, Women of Japan, five women sit in the middle of a picture plane, surrounded by white birds and the cage from which the birds must have flown. Painted in the early 1970s, around the time she was in Japan, the figures’ elongated faces and their inked-out style were probably inspired by this trip, and the colour shows a flatness that sets it apart from her usual, worked upon oil style.

-

Feryal Matar, Women of Japan, silk, silk pigment, c. early 1970s, around the time she studied ikebana in the country. -

Feryal Matar, رجال البحر من سلسلة التراث الاماراتي (Men of the Sea), 1987, oil on wood board, 227 x 182.2cm

Matar also draws inspiration from the nation-building of the Emirates, again a typical subject. The large-scale, history-painting size Men of the Sea (1987) shows a group of men in a wooden boat: the black, unclothed sailors and the man with his till on the rudder in a white thobe (the traditional male Gulf dress). Behind this scene, which seems to evoke the past of pearl diving (and its reliance on indentured labourers from Africa),05 a new bridge rises in the distance – a meeting of old and new through which Matar and others made sense of the rapid changes then occurring in the UAE. In another, a dhow (a traditional Gulf boat) idles against a sunset, the colours of the sky suggesting a placidity and eminence of nature that is echoed in the calm sea. Her interest in the sea and beaches cross media as well: one painting shows two falcons fighting in the sand, which she has evoked by affixing real sand across the picture plane.

Matar’s work with other material is perhaps the most interesting part of her practice. In addition to easel painting, Matar has created painted floral motifs and designs on silk robes; calligraphy made from thin nails she has hammered into bolts of black velvet; carved wooden figures, such as intricately moulded spheres or chubby animal forms; sculptural collages made of rams’ horns; glass etchings, again mostly in a calligraphic mode; metalwork across a variety of platforms; and images made of shells and sand. The calligraphic experimentations are often rooted in Islamic forms, which she learnt in her degree (the injazat) that she earned in calligraphy. She also surpasses recognisable idioms with whole fields she seems to have invented herself. Her daughter showed me cast-iron presses she had commissioned of leaves and flowers she found in Sharjah, providing her with a way of rendering the natural world around her into exact ceramic replicas. She would put the clay into the hot press – almost like a waffle maker, with the design for the leaf or flower on both sides – and close the top and bottom together and wait for it to cool. She made jewellery and then – like a cherry on top – designed her own logo out of her initials in Arabic, ف (M) and م. (F). These works are not so much ‘craft’ as part of a cultural tradition that did not see a division between ‘high’ and ‘applied’ art. Indeed, she has sold these works alongside her paintings to a collector base that includes royalty including sheikhs as well as dignitaries and members of the emerging professional class in the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

-

An image from the 1970s shows Feryal Matar (third from right) at lunch with His Highness Sheikh Sultan bin Mohammed Al Qasimi (third from left) in Sharjah. -

Feryal Matar (standing, rightmost) teaching an art class as a young woman in Kuwait.

Matar the Teacher

The subject of Sharjah’s developing civil society has not just been the background to Matar and Abu Kuwaik’s role within the UAE: they have been driving forces within it. The family is part of a generation of Palestinians who were encouraged to move to the UAE because of their level of education and professional qualifications – often from the interim landing point of Kuwait, where they fled to after the Israeli takeover of their country.06 While Dr Abu Kuwaik set up his medical practice, Matar educated generations of women artists. She was incredibly dedicated: she taught different classes throughout the day, often pausing only for a quick lunch and then working until 8 p.m. at the Sharjah Women’s Association.

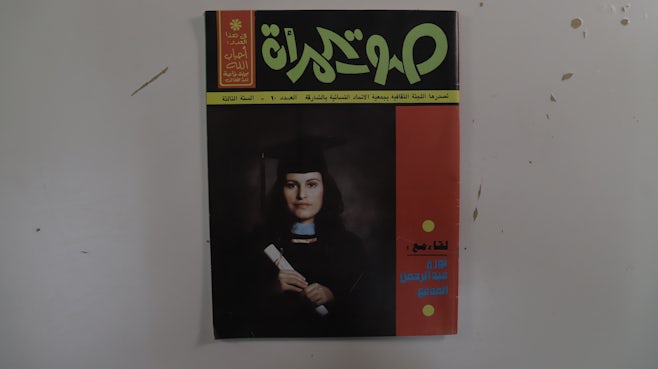

The Women’s Association was one of a number of such gathering places set up across the UAE in the 1970s.07 (Associations exist across the UAE based on all sorts of affinities, such as the Indian Social and Cultural Centre, the Automobile and Touring Club, the Sudanese Social Club and the Tourist Club.08) Members comprise new transplants to the region, so-called ‘trailing spouses’, from American, European and Arab professional classes, and from local Emirati families apparently of all classes. The idea of the Women’s Association was to teach what were deemed modern skills to a population that was newly coming into wealth and whose lifestyles were changing rapidly, with classes in literacy, childrearing and crafts, as well as to provide a space for women to exchange ideas and relax. In such a way they sat between the mission civilisatrice of colonial betterment and a site of sociality and empowerment for women, with peer-led knowledge-sharing and advice. The house magazine, titled Sawt Al Mara’a (Women’s Voice), is by turns cringeworthy and familiar: an edition that featured Matar in 1986 included an article by the partner of a British diplomat on how to be a good wife; another piece offered advice for how women should balance family and career commitments; still another gave guidance on dinner party etiquette.

Matar was the founder and head of the art section for the association, which sat on what is known as the Cultural Roundabout, in the building that is now the Sharjah Library (it moved closer to the Sharjah Science Museum in the 1990s). She acquired this role in part through the patronage of Sheikha Noora Al Qasimi, the wife of Saud Khalid Al Qasimi, then the ruler of Sharjah. Her students, all women, had varying degrees of commitment to art making. Matar dealt with that by introducing a three-tiered system in an attempt to professionalise the qualifications: students could achieve an ‘advanced level’, or a two-year degree that would allow the student to work as an art teacher in the Ministry of Education. An ‘intermediate level’ course of one month consisting of teaching students one skill; and another ‘beginner’ level, a six-month course that would allow the participant to start her own business and research further in that particular skill. Her subjects were painting in oil and acrylic and drawing, as well as a variety of other kinds of creative disciplines: mixed-media artworks, including from found material; making flowers with media such as fabric, paper, metal, plastic and clay; flower arrangements and painting flowers on vases and canvas; decoupage; painting on glass (including sanding and free drawing); metalwork; painting on textiles; painting, stencil and wax-blocking design on silk; and interior design. Matar offered degrees in all of these, with most women achieving intermediate or advanced levels. The students were drawn from the Sharjah Women’s Association’s general membership, and most did not become artists. However, the education can be considered successful by other metrics: many of them became businesswomen and teachers. And those who remained housewives were given greater skills and autonomy outside the home.

Craft in the UAE

Another society created at the time was the Emirates Fine Arts Society (EFAS), which established itself – again through the royal patronage, this time of the enlightened ruler Sheikh Sultan bin Muhammad Al-Qasimi, who succeeded his brother in 1972 – in 1980 near the city’s Corniche. The founding of EFAS is the first major step in the recognised infrastructural development of art in Sharjah, followed by the launching of the Sharjah Biennial in 1993, the Sharjah Art Museum in 1997, and Sheikha Hoor Al Qasimi’s levelling up of the biennial in 2003. EFAS developed out of a group of artists and poets who began working in the 1970s and 1980s and who agitated for places to work, meet and exhibit. There, they showed calligraphy, abstract oil paintings, and, to a lesser extent, work in installation and performance. They came from the UAE as well as across the Arab world, and looked to art as a way to establish new cultural idioms that matched the economic and social change around them. Some of these names are now famous in the Gulf and internationally, such as Hassan Sharif, Mohammed Kazem and Mohammed Ahmed Ibrahim.

It would be easy, at this point in the story, to set Matar as the woman who does not belong to EFAS, and the EFAS artists as those who were launched onto the international circuit. Matar was indeed a generation before EFAS and was not part of their circle, though she participated in the odd exhibition (and showed locally and internationally before the establishment of EFAS). But the EFAS artists are also in need of further study: while they too showed on a regional circuit, only a handful of them became known in the West, where they were referred to the ‘Five’.09 Most of them are still working, and represent a parallel, Arabic-speaking path to the English-speaking contemporary artists who today dominate international attention via sites such as Alserkal Avenue, the Jameel Arts Centre and 421.

Matar, however, reflects a separate, rather than a subordinated history. Part of the story of the UAE’s success on the international circuit has been its embrace of Western idioms, such as Sharif’s Fluxus-inspired performances that he developed after he studied at Byam Shaw School of Art in London. Matar’s applied work, however, reflects disciplines that sit somewhere between traditional craft practices – now coded as artistically credible – and representational oil painting (ironically, now coded as outdated). They fall into a lacuna of work that is rarely shown on the international or market circuit, with its ultra-high-net-worth collector class and art professionals schooled in theory and Conceptualism. They remain popular, however, in many middle-class houses as a form of decoration, and often speak to the home’s cultural identity, as most decor taste choices tend to do.

Just how separate these idioms are from ‘craft’ can be seen by comparison with other apparently similar sites that operated across the Middle East over a roughly similar time period, which used craft to different ends. Both under colonialism and in the postcolonial era craft idioms functioned as a resource for defining an authentic or postcolonial identity. Reacting to Beaux-Arts teaching, for example, the artists of the Casablanca School in the 1960s and 70s drew from the motifs and practices of the Amazigh people to inform their canvases, graphic design, metalwork and calfskin artworks. The artists of the Khartoum School in the 1960s, such as Ibrahim El-Salahi, looked to folk stories, music and vernacular crafts from Sudan to create artwork that would match the postcolonial moment; they even set up an academic programme at the University of Khartoum, the Sudanese Research Unit, to formalise study of this field, in 1964. In post-independence Tunisia, the artist Safia Farhat worked with female weavers via the National Office of Handicraft, helping to spur the take-up of tapestry as an artistic medium, and to support women textile artisans. As an agency of the government, it formed part of President Habib Bourguiba’s state-crafting policy, which privileged tapestry as an authentically Tunisian cultural form.10

However, as taught at the Sharjah Women’s Association, there was little sense of applied art either drawing from a lost tribal identity or contributing to the contours of a new national identity. This stands in direct contrast to the way craft skills are instrumentalised today in the UAE, in its many heritage festivals and sites such as the well-funded House of Artisans in Abu Dhabi. Bedouin heritage now serves an expressly nationalist purpose of linking the UAE state to the specific, racially Arab tribes that predated the UAE federation. But in the 1970s and 80s, Matar and Dr Abu Kuwaik were agents of modernisation: initiating a movement away from Bedouin practices, which were perhaps too recent to be considered truly lost. This reading is buttressed by the nature of the practices themselves, which hew closer to fine ornamentation than the earthy evocations of tribal craft.

As part of the specific UAE story of nation-building via oil, Matar’s work also points towards an important function of art- and applied art-making: how it operated as a form of accountability and sociality. Matar saw her work at the Sharjah Women’s Association less as an art practice and more as a way to empower women, as we have seen, and knowingly operated in a straitened field. Few women in the UAE at the time aspired to the status of professional artists – unless, like Matar, they had had the chance to be educated abroad, and she was aware of her separate standing. An analogue for Matar’s art department can be seen in Saudi, which had a more developed historical art scene but displayed similar social constraints. The painter Safeya Binzagr (who attended Saint Martin’s School of Art, now Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London) held painting classes for women and boys at her studio-cum-exhibition site, the Darat Safeya Binzagr in Jeddah, throughout the 1980s to 2000s. Notably, Binzagr’s Darat (meaning ‘place’) also incorporates applied art, in the artist’s careful collecting of exemplars of the many different tribal forms of dress that were once common across the Arabian Peninsula. Binzagr painstakingly represents these clothes in identically sized watercolours that recall Conceptualist taxonomies – but she prefers to show off her oil painting to visitors, even though these are (at least from a Western perspective) less accomplished. Matar, too, has downplayed her experiments in craft in favour of her oil paintings. Not only do both artists – each of whom lays plausible claim to being ‘the first woman artist’ of their countries, if that superlative means anything – seem to have internalised the gender divisions between art making and craft, but also the Western hierarchy between them.

It’s tempting to see Matar as a contemporary artist avant la lettre, working in idioms such as textiles, mixed-media and ceramics that are now being globally (re)integrated into the forefront of contemporary practice. It’s also tempting to see a postcolonialism at play in Matar’s espousal of non-Beaux-Arts idioms. But, again, Matar herself has identified as an oil painter, and thought of her applied and teaching work as secondary. And the terms associated with the above analyses – the idea of being at the forefront of practice or against European colonialism – were not part of the motivations behind Matar’s artwork. Instead, we might see in these very questions, and my claims of where Matar’s and Binzagr’s ‘best’ work is, my own Western biases, so readily slotting non-Western artists in the category of applied art. If this is a moment of radical reorganisation of taste, I don’t envy museum curators with their expensive acquisition lists and bricks-and-mortar galleries – devices not made for openness and change as the field of contenders worthy of attention opens across classes, genders and social spaces.

Footnotes

-

Abu Kuwaik is an artist in her own right, often following on from her mother in painting or in clothes design. This text is adapted from a forthcoming essay on her work commissioned by Abu Kuwaik, and draws on studio visits and meetings with Abu Kuwaik and Matar over the course of 2022–23.

-

The certificate remains in Matar’s archives at her home.

-

Today, the Matar and Abu Kuwaik houses are dwarfed by the bustle around them: the Flying Saucer – now a venue for the Sharjah Art Foundation – was built opposite, and a vortex of traffic forms a ring of Saturn around this futuristic building. Sound floods the garden – now tiled over – from a highway flyover as it hooks by on its way towards Dubai. A third, modern building, the ZAK Smart Medical Services building, faces the street.

-

According to Abu Kuwaik, this work is now in the collection of Sheikh Dr Sultan bin Muhammad Al-Qasimi, the ruler of Sharjah. A copy, which Matar often made of her works, remains at Matar’s studio.

-

Slavery wasn’t outlawed in the UAE until 1963. Enslaved labourers and indentured servants performed domestic duties and furnished part of the pearl-diving labour force. Matar’s painting is one of the few to picture this practice, which remains a sensitive topic in the Gulf.

-

See Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi and Todd Reisz (ed.), Building Sharjah, Basel: Birkhäuser, 2021.

-

See Vânia Carvalho Pinto, ‘The “Makings” of a Movement “by Implication”: Assessing the Expansion of Women’s Rights in the United Arab Emirates from 1971 Until Today’, in Pernille Arenfeldt and Nawar Al-Hassan Golley (ed.), Mapping Arab Women’s Movements: A Century of Transformations from Within, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012, pp.281–302.

-

In 2017, the curators Reem Fadda and Maisa Al Qassimi explored these associations in their edition of ‘Emirati Expressions’, a now-defunct annual exhibition that was held at various locations in Abu Dhabi from 2009 to 2017, with some interruptions.

-

This term is contentious but refers to Hassan Sharif, Hussein Sharif, Mohamed Ahmed Ibrahim, Abdullah Al Saadi and Mohammed Kazem.

-

See Jessica Gerschultz, ‘Women’s Tapestry and the Poetics of Renewal: Threading Mid-Century Practices’, The Journal of Modern Craft, vol.13, no.1, March 2020, pp.37–50; J. Gerschultz, Decorative Arts of the Tunisian Ecole: Fabrications of Modernism, Gender and Power, University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2019.