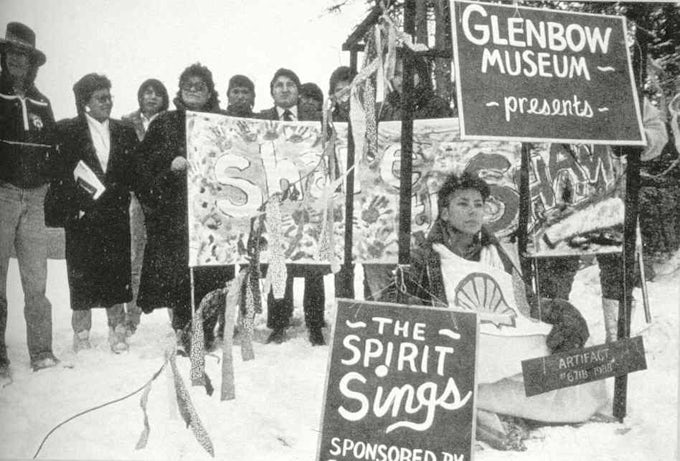

In 1986, while working in a university museum in the US state of Maine, I began to hear media reports regarding the planning of an exhibition titled ‘The Spirit Sings: Artistic Traditions of Canada’s First Peoples’.01Organised by the Glenbow Museum in Calgary, Alberta to coincide with the 1988 Olympics held in that location, ‘The Spirit Sings’ was to include over 650 historical objects borrowed from national and international ethnographic collections.02 I was angry and frustrated to learn that the curatorial committee included no Indigenous curators. My anger was exacerbated by the fact that the exhibition would include only historical objects, without regard to contemporary realities – typical of the exclusionary practices of museums that had amassed significant collections of Indigenous historical objects while denying intellectual and physical access to the objects by the very communities from which they were taken.

I was not alone in my anger. ‘The Spirit Sings’ was part of a sequence of exhibitions and events during the late 1980s and early 90s that profoundly impacted the content of, and contexts for, exhibitions of Indigenous art. Artistic and community activism, exhibitions, conferences and a task force forever transformed relationships between museums and Indigenous peoples in Canada; this essay is an attempt to weave together a history of the turbulent dynamic of this time.

The fact that ‘The Spirit Springs’ came to my attention as early as 1986 can be attributed to a widely publicised campaign by the Lubicon Cree Nation – a small Aboriginal community living sovereignly in northern Alberta – to boycott the exhibition, which brought issues of museum representation and First Nations cultural heritage to the forefront of the national debate. From the perspective of the Lubicon Cree, the exhibition glorified numerous romantic stereotypes associated with historical Aboriginal cultural objects while denying complex contemporary realities. In their case, that reality was the destruction wrought on their culture and livelihood by Shell Canada, the corporate sponsor of the exhibition, as well as the complicity of major cultural institutions in Shell’s corporate agenda, through organising or lending work to the show. Indigenous artists, communities and political organisations across the nation strongly supported Lubicon’s perspective and boycott.

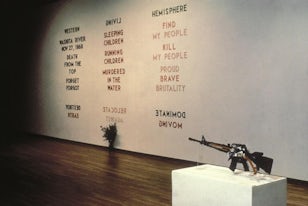

On 12 January 1988, three days before ‘The Spirit Sings’ opened to the public, Rebecca Belmore burst into the national arts consciousness with her performance piece Artifact #671B. In minus 18 degrees Celsius weather, she sat immobile on the frozen ground in a museum case outside the Thunder Bay Art Gallery in Ontario. Her performance expressed the collective anger of the many Indigenous people throughout Canada who condemned the organisers and sponsor of ‘The Spirit Sings’. Four days earlier, the exhibition ‘Revisions’ had opened at the Walter Phillips Gallery in Banff, Alberta (about an hour from Calgary). Strategically timed to coincide with ‘The Spirit Sings’, ‘Revisions’ included eight Indigenous artists from both Canada and the US.03 Conceived to counter the historic and ethnographic focus of ‘The Spirit Sings’, ‘Revisions’ asserted the significance of contemporary Indigenous culture and arts practices. The artists sabotaged ethnographic stereotypes in order to redress their present and future cultural identities. They were concerned with ‘deconstructing Eurocentric versions of native history and proposing their own counternarratives’;04 for example, Jimmie Durham and Joane Cardinal-Schubert both angrily parodied the devices of museum display as they created their own contemporary artifacts as history lesson and ethnographic critique. These interventions responded to the housing of Indigenous artifacts in Caucasian museums in North America and in Europe and the categorisation of Indigenous art practices in ethnographic terms. (These conditions are largely still the case.) Even with the growing public awareness of Indigenous sovereignty in the late 1980s, sympathy for Indigenous peoples was usually based on paternalistic notions of cultures forever locked in history. While ‘Revisions’ was important as one of the first exhibitions to focus on the disruption of institutional practices through an Indigenous lens, its impact was limited until the accompanying catalogue was published in 1992.

In conjunction with the last days of the second presentation of ‘The Spirit Sings’, from 1 July–6 November 1988 at the Canadian Museum of Civilization 05 in Gatineau, Quebec (across the river from Ottawa), the Assembly of First Nations and the Canadian Museums Association jointly organised a conference to debate the full range of concerns voiced by the Lubicon Cree. ‘Preserving Our Heritage: A Working Conference Between Museums and First Peoples’ brought together over 150 academics, artists, curators, museum professionals, politicians and Indigenous knowledge keepers. Sponsorship, representation, access to collections and training were some aspects of the vital and multifaceted discussions at this conference. Following the recommendations of conference participants, and officially initiated by the Assembly of First Nations and the Canadian Museums Association in 1990, the Task Force on Museums and First Peoples – for which I was coordinator – convened consultations and meetings and conducted research over a two-year period. The final report, Turning the Page: Forging New Partnerships Between Museums and First Peoples (1992), contains guidelines and recommendations ‘to develop an ethical framework and strategies for Aboriginal Nations to represent their history and culture in concert with cultural institutions.’ 06

At this time I also conducted an independent survey on the status of contemporary Native art within 29 contemporary Canadian art institutions; this involved studying a number of museum functions: acquisitions, exhibitions, publications, programming, staffing and relationships to Aboriginal (arts) communities.07Written acquisition policies of the period contained subtle exclusionary phrases such as ‘highest quality collections’, ‘finest visual art available’ and ‘important artists’; such language was used to denote a single acceptable standard, to perpetuate the myth of the Western European model of race hierarchy and to deny the complex issues of diverse art discourses and practices. The study concluded by detailing the systemic exclusion of contemporary Indigenous art from Canada’s foremost art museums.

With few exceptions, curators and directors rationalised this exclusion with statements that they didn’t want to ‘segregate’ or ‘reduce to a ghetto status’ these works. Although many stated that they were fearful of ‘different’ treatment for these artists, they overlooked the fact that contemporary Aboriginal artists had been treated differently and negatively for far too long. The majority of the museums displayed an aversion to thematic exhibitions based ‘solely on cultural origins’ of artists; the integration of contemporary Indigenous art with contemporary Canadian art seems to have been beyond their scope at that time.

•

The mobilisation around ‘The Spirit Sings’ built upon years and decades of Indigenous activism, organisation and resistance. I became increasingly aware of this as of 1987, when I began graduate work in museum studies at the University of Toronto, to research, critique and enter into a field less travelled by Indigenous peoples at that time. I soon learned about the third National Native Indian Artists Symposium that was organised at K’san, British Columbia in 1983, where Kwakwaka’wakw and Haida artists who had worked on museum projects in Victoria and Vancouver during the previous two decades shared their skills with over a hundred artists and students.08 (The symposium itself was held on the site of the Kitanmax School of Northwest Coast Indian Art, which in 1967 had initiated an artist training programme to revitalise Nisga’a art and cultural traditions.)

Immediately following the symposium, a working group was organised to address the ongoing exclusion of Indian art by mainstream art institutions; the group incorporated as the Society of Canadian Artists of Native Ancestry (SCANA) in January 1985. Two artists highly respected as innovators within their respective traditions of Iroquoian sculpture and Northwest Coast sculpture, David General and Doreen Jensen, were the first co-chairs of SCANA. Throughout the 1980s and the early 90s, the group worked tirelessly to increase the recognition of contemporary First Nations artists. The mandate of SCANA, as an informally organised national group, was to act as liaison amongst the growing number of Native artists, the provincial and federal funding agencies, and art museums. It was a strong advocate in the many debates around museum representation in this period; amongst its accomplishments was the organisation in 1987 of ‘Networking’, the fourth National Native Indian Arts Symposium, at the University of Lethbridge, Alberta. 09

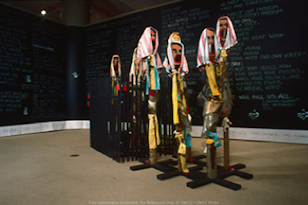

Importantly, SCANA also collaborated with several cultural institutions to develop exhibition projects, including the pioneering ‘Beyond History’, presented at the Vancouver Art Gallery in 1989.10 A partnership involving SCANA, the Woodland Cultural Centre and the Vancouver Art Gallery, this exhibition signalled ‘the creation of a new ideology which is highly personal and political, unlike the collective tribal response proclaimed during the sixties’.11 ‘Beyond History’ included mixed media works by artists who came to prominence in the 1980s, and who shared a critique of popular ethnographic stereotypes and a focus on the impact of colonisation in Canada on Indigenous peoples. However, these artists were by no means a homogeneous group: they came from different cultural heritages, art traditions, political persuasions and personal experiences.

Parallel to the activist history of Aboriginal artists, First Nations artist-run centres also emerged throughout Canada beginning in the 1980s. This movement exemplified the ways in which artists seized control of how their art was presented, providing alternative spaces free from the limitations of public institutions. The Native Indian/Inuit Photographers’ Association in Hamilton, Ontario was the first such collective, created in 1985; by the mid-90s other centres were operating with broad, multidisciplinary mandates, amongst them Sâkêwêwak Artists’ Collective in Regina, Saskatchewan (1993); Tribe Inc. in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan (1995); and Urban Shaman Contemporary Gallery in Winnipeg, Manitoba (1996). Additionally, the Aboriginal Film and Video Art Alliance (formed in 1991) was instrumental in developing the framework for the multidisciplinary Aboriginal Arts Program at the Banff Centre in 1995.

During the late 1980s, the mounting debates surrounding the inclusion of contemporary Indigenous art and access to historical collections were compounded by a turbulent sociopolitical landscape in Canada. Land claims and struggles against corporate deve-lopment resulted in direct action by First Nations communities throughout the country. By 1990, political events galvanised Indigenous solidarity and provided the impetus for heightened activities that would resonate throughout the next decade. Massive land claims were slowly proceeding in British Columbia, Ontario and the Yukon; the Quebec government announced plans to begin the second phase of the James Bay hydroelectric project; and the late Elijah Harper, a Cree member of the Manitoba Legislative Assembly, said ‘No’ to the Meech Lake Accord, the proposed constitutional legislation that would have denied recognition of Aboriginal peoples while affirming the province of Quebec as a distinct society with special status.

And then there was Oka. For 78 days in the summer of 1990, the Mohawk people of Kanehsatake defended their land against the impending encroachment of a golf course in the neighbouring town of Oka, in Quebec. The Canadian Armed Forces and the Quebec Provincial Police used physical force against the many people who struggled to defend their land. Once again, artist Rebecca Belmore produced a powerful artwork. For her community-based performance and sound installation Ayum-ee-aawach Oomama-mowan: Speaking to their Mother (1991–96), Belmore travelled to First Nation communities and urban areas throughout Canada and the US, inviting people to address the land directly in response to the Oka standoff. Hundreds of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people joined in addressing Mother Earth through a megaphone encased in a massive wooden amplifier bound together with leather and animal hides.

•

In 1992, official events marked the 500th anniversary of the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the Americas, a largely Italian-American celebration of ‘discovery’ that was receiving considerable funding and media attention on both sides of the Atlantic. Indigenous peoples did not share this celebratory spirit, as the legacy of European colonisation has largely rendered Indigenous peoples invisible in their own territories. But 1992 was also the culmination of a decade-long escalation of Indigenous frustration in Canada, with a colonial state that steadfastly refused to uphold the rights that had been recognised and affirmed in the Constitution Act of 1982. Once again, artists raised their voices in anger, reflection, conciliation and affirmation of cultural identity. Following 500 years of oppression and exclusion, Indigenous peoples tenaciously affirmed their own histories, experiences and identities within a thoroughly contemporary context.

That year, two international touring exhibitions heralded a significant new direction for the production and presentation of contemporary Aboriginal art in Canada. ‘INDIGENA: Perspectives of Indigenous Peoples on Five Hundred Years’, curated by myself and Gerald McMaster, opened at the Canadian Museum of Civilization; across the Ottawa River, ‘Land Spirit Power: First Nations at the National Gallery of Canada’ was the result of the curatorial collaboration of that institution’s Diana Nemiroff, independent curator and Saulteaux artist Robert Houle and anthropologist Charlotte Townsend-Gault. ‘INDIGENA’ was the first Indigenous-curated internationally touring exhibition organised by a high-profile national institution. Its organisation began in the mid-1980s, while I was living in the US, where I worked with colleagues – Tewa curator Margaret Archuleta and Tlingit artist Jim Schoppert – to develop a national project to de-celebrate the impending quincentennial of Columbus’s arrival; I continued the project in Canada in collaboration with McMaster. (SCANA also supported the exhibition project by providing a grant for my curatorial fee.) Our primary audiences were the Euro-Canadian and US occupiers of the Americas. We hoped to shock non-Indigenous viewers out of their complacency and ignorance of Indigenous history and contemporary realities. But we also hoped to connect with Indigenous audiences throughout North America who knew about and lived this painful history.

The government of Canada chose not to recognise the quincentennial of the United States. But they did plan to celebrate the 125th anniversary of Canada. As Indigenous curators, we could not acknowledge any such celebrations of Western dominance and oppression, so we seized that moment to present, on our own terms, issues of importance to our communities. ‘INDIGENA’ was a logical extension of the Canadian Museum of Civilization’s commitment to contemporary Indigenous art; the museum had opened three years earlier, and many of its staff members were participants on the Task Force on Museums and First Peoples. The exhibition brought together works by visual, literary and performing artists from across the country that engaged in an Indigenous critique of 500 years of colonial history. Essays, performances, paintings, installations, videos and photographs examined the tangled complex of history, language, identity, stereotypes and contemporary realities that defined Indigenous cultures at the time. The primacy of Indigenous voices, representation and community support were central tenets of the project; hosting venues in both Canada and the US were selected based upon the involvement of local Indigenous communities.

Opening in September 1992, and overlapping with ‘INDIGENA’ for one month, ‘Land Spirit Power’ was the first major international exhibition of contemporary First Nations art from Canada and Native American artists from the US to be held at the National Gallery of Canada. The curatorial premise sought to ‘recognise a new generation of First Nations artists whose work was individual and personal, yet reflected a distinct cultural experience within mainstream North American art’.12 Most of the artists, including three who were also exhibiting in ‘INDIGENA’ (Carl Beam, Domingo Cisneros and Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun), worked within contemporary mainstream idioms. ‘Land Spirit Power’ also presented the work of artists who contemporised their culture-specific and customary practices (Dempsey Bob, Robert Davidson and Dorothy Grant were noteworthy in this respect). This exhibition was significant in including diverse artists who expressed their ‘distinct cultural experiences’ through individual notions of the land as a spiritual and political legacy.

As two of the first major exhibitions of art and contemporary issues as seen through Indigenous lenses, ‘INDIGENA’ and ‘Land Spirit Power’ disrupted long-held institutional discourses and practices. They mark an important turning point, and the point at which I will end this brief history. Writing today, 25 years later, I remain angry and frustrated. Indigenous arts professionals throughout Canada and the world have developed a formidable intellectual force that challenges the basic premise of Western mandates and practices. But drastic conditions still exist throughout Canada – evidence of the persistence of the country’s colonial history and its lingering effects today. Thousands of missing and murdered women, high rates of suicide amongst our youth, the incarceration of Indigenous men, poverty, lack of drinking water and educational needs plague our communities – not to mention the constant struggle for sovereignty over traditional lands. Much work remains to be done.

Footnotes

-

Note on terminology: ‘Indigenous’ is the preferred terminology used today with specific reference to the arts in the Canadian context and internationally. However, throughout this text, I use the terms ‘Native’, ‘Indian’ and ‘First Nations’ to respect their historic context and usage in Canada.

-

The exhibition ran from 15 January–1 May 1988 at the the Glenbow Museum, before travelling to the Canadian Museum of Civilization in Ottawa, 1 July–6 November 1988.

-

‘Revisions’ took place 8–28 January 1988. The participating artists were Joane Cardinal-Schubert, Jimmie Durham, Hachivi Edgar Heap of Birds, Zacharias Kunuk, Mike MacDonald, Alan Michelson, Edward Poitras and Pierre Sioui.

-

Helga Pakasaar, in Revisions (exh. cat.), Banff, Alberta: Walter Phillips Gallery, 1992, p.3.

-

Now the Canadian Museum of History.

-

Turning the Page: Forging New Partnerships Between Museums and First Peoples, a report jointly sponsored by the Assembly of First Nations and the Canadian Museums Association, Ottawa, Ontario, 1992.

-

The study was supported by the Canada Council as part of a residency I was then undertaking at the Canadian Museum of Civilization, Gatineau, Quebec.

-

Funded in part by the federal Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (now Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada), previous symposia included: Symposium I, Manitoulin Island, Ontario, October 1978; and Symposium II, Saskatchewan Indian Federated College, Regina, Saskatchewan, September 1979.

-

At this event, artists and representatives of Canadian arts and funding institutions debated issues surrounding the definitions of and contexts for contemporary Indigenous art. See Alfred Young Man (ed.), Networking: Proceedings of the Fourth National Native Indian Arts Symposium, Lethbridge, Alberta: University of Lethbridge 1987.

-

Karen Duffek and Tom Hill, Beyond History (exh. cat.), Vancouver: Vancouver Art Gallery, 1989.

-

Ibid., p.5.

-

Diana Nemiroff, Robert Houle and Charlotte Townsend-Gault, ‘Land, Spirit, Power’, in Land Spirit Power: First Nations at the National Gallery of Canada (exh. cat.), Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 1992, p.11.